Author, singer-songwriter, and professional publisher Malika Kolessova discusses her project “Me and My Invisible Orchestra,” her publishing initiative Tentek, and points of potential intersection between the Kazakh and Russian languages.

Dreams

My name is Malika Kolessova and I’m 30 years old. I was born in Uralsk, and I’ve been in Almaty for four years now, though I lived in Saint Petersburg for 10 years before that.

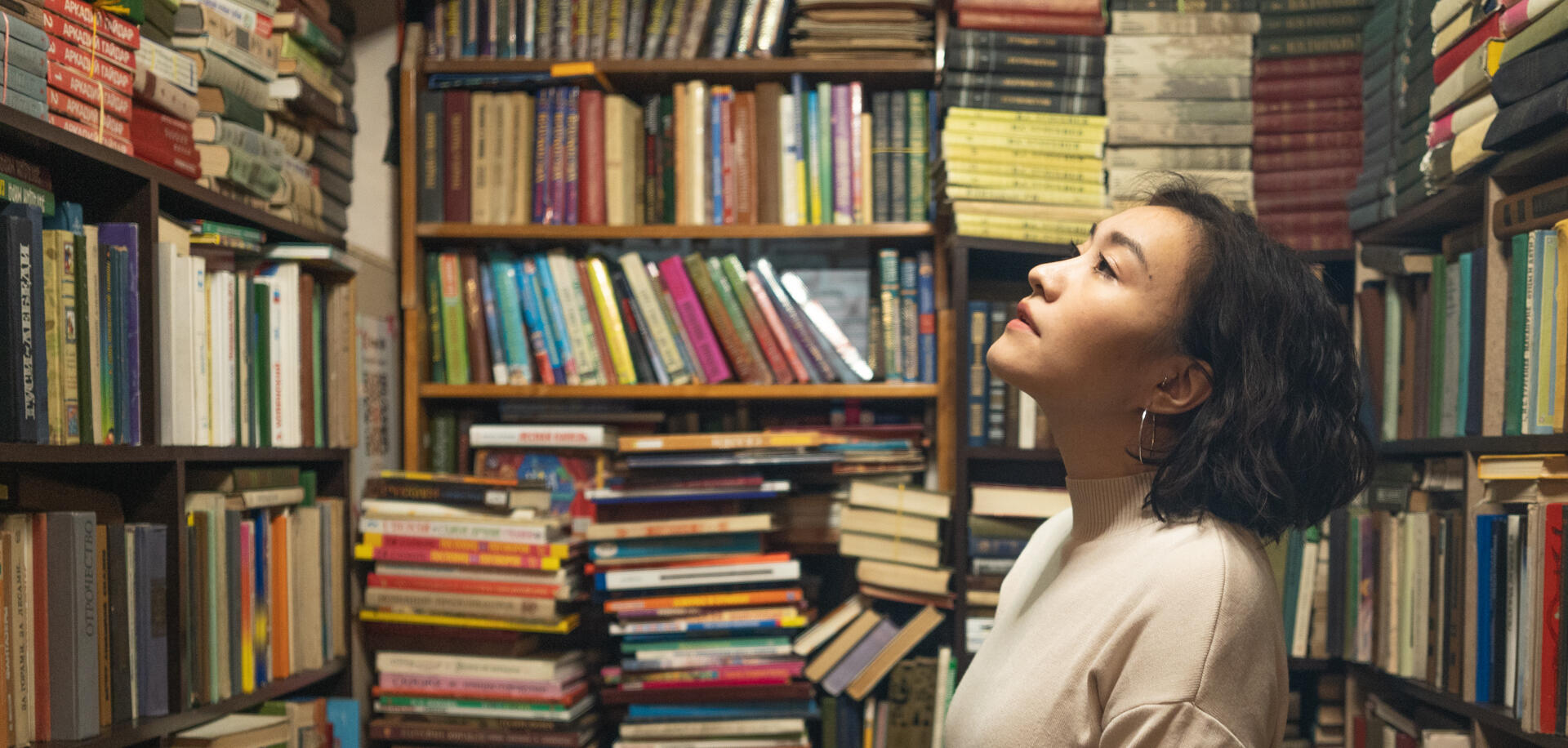

My mother works as a Russian language and literature teacher, and we always had a lot of books around the house. As a child, I loved to read and flip through them. I was a homebody, always doing something around the house, drawing, listening to records. I dreamed of being a singer, and when I got older—a director. But books always held a special place in my heart. Of course, that's how life works: your dreams come true in reality, just differently than you thought. Now I do music with the project, “Me and My Invisible Orchestra,” and I’m also a professional publisher. I’d really like to do something good for children’s publishing in Kazakhstan.

Music

Like many of my peers, I really loved Britney Spears as a kid. But by the time I was a teenager, I was listening to completely different music, and was even a member of a punk rock group. I dyed my hair, played the guitar, and got a tattoo at a very young age...which I regret to this day.

When I was 13, my mom bought me my first guitar at a shop called “Seven Notes” in Uralsk. The guitar was very green, really strange-looking, but I started strumming chords and singing all the songs that I’d been listening to, and that was that.

Me and My Invisible Orchestra

I went to college when I was 17, moved to Saint Petersburg, and was plunged into a totally different world. I learned to write my own songs in English and French my first year at university, recorded them on a dictaphone and started putting them online.

Why is the group called “Me and My Invisible Orchestra”? Everyone has that question. Basically, I needed to make a group on VKontakte so that I could put stuff there, and I was thinking that there’s me and there’s the invisible orchestra that accompanies me in my head—like it’s there but not there at the same time. And so that’s where the name was born.

Saint Petersburg

In St. Petersburg I was studying to do communications and PR, but already by the second week I knew it wasn’t jiving with my personal principles for interacting with people, and I wasn’t really interested in it. When we got the chance to choose an organization for our practical portion, I thought I’d like to know how books were made.

So, my junior year I went to work in publishing, and I liked it a lot—how intellectual labor can transform into something physical brings truly mind-boggling joy. At first I was an intern, bringing coffee, helping, and next thing I knew I had been in publishing for six years already. I learned a lot there, and eventually became a publisher myself.

I studied at Petrogradka and worked on Vasilievsky Island. Generally, I woke up in the morning, went to the office, worked a bit, went to lectures, and then headed back to work: engaging with authors and taking orders. Every once in a while I’d get a free moment, and I would take a quick nap in the designer’s office, just to keep up my strength. That’s how I got through my education, and after university I continued working in publishing—but as a free person at that point.

At the university, the only people from Central Asia were me (from Kazakhstan) and a guy from Turkmenistan—that’s it. As a result, I experienced some things that people talk more often these days: the perceptible tinge of xenophobia, chauvinism. That definitely happened, but Saint Petersburg in and of itself, and many of the people there, were cool. To this day I love that city, especially the sunny days...the one sunny day that you get per year, I mean. But at a certain point I realized that there wasn’t a path for me there anymore. There was a sort of stagnation, internally and externally. It’s possible that local politics also influenced or made an impression on how I was feeling. And maybe I just finally heard the call of my native steppes (I'm only half-kidding). You can’t run from yourself—at some point, you want to figure out who you are and that, maybe, is the most obvious, though nevertheless true, kind of self-identification.

Almaty

In 2016, my mother and I met in Almaty for vacation. I walked around the streets with a heavy backpack and knew right away that it was my city. To this day I remember the exact streets that I wandered around, though they were unknown to me then. I felt that it was a place I’d like to live, to be, to grow. But it wasn’t a simple step to just up and leave Saint Petersburg: my work was there, obligations, and I wasn’t quite sure if I wanted to return. But there was definitely the feeling of “my” city, the history, the nice parts. In Almaty I didn’t feel that stagnation; in fact, it was the opposite—I felt something good coming, changes. And two years later I finally made the move from Saint Petersburg to here. I found work at a pop science magazine and, at the same time, started to make music more professionally.

Creative work

At this point, “Me and My Invisible Orchestra” is composed of me and my partner Konstantin Kohan. Kostya is a music producer, so our creative process is split: sometimes he’ll have a stroke of musical genius, and I’ll write the lyrics for it. Other times I’ll come up with a draft, a demo with a simple accompaniment, and Kostya shapes it into something more finished.

My songs are a reflection, meaning of me—and my internal monologue. I don’t write much about the external world, more about attempts to know myself and my place in it. Sometimes these musings broaden into something more external. It happens that a phrase or something will come to me, or I can take a thought from somewhere that strikes a chord deep down, and continue to develop it...That’s how the song takes shape. There was a time when I bought a guitar capo, started strumming some chords I didn’t usually play, and from that came the song “Undeme” (original in Kazakh: Үндеме, translation: "Be silent")—just from that first chord I played. I still haven’t talked about this, but the mood of “Undeme” was inspired by the events of our Kazakh Spring . The song was written around that time, and it’s how I was feeling during those events: how to act, should I do something, why are we not afraid to die, but afraid to live without shame. But even writing that song with inspiration from those events, it became something bigger, more general, more philosophical.

Publishing in Kazakhstan

When I came back to Kazakhstan the first thing I did was look through all the bookstores to see what was there. Unfortunately, the amount of Kazakh-language literature, or even just literature written by Kazakhstani authors, sold here in the children’s section is basically nothing. You might find a handful of publications from the bigger local publishers, even some more substantial, but they’re always so flashy, so lurid, and that just doesn’t fit with what I’d imagine.

There are fantastic publishers that work with translated literature, for example, Steppe & World Publishing. They’re amazing, but it seems that they don’t work extensively with local authors yet.

I’d like to build up the local community so that our local authors have the opportunity to be printed, published, sold in stores—to have a chance to bring their work not only to the audience whose language they write in, but to everyone else, too. These days, in our society, I’d say there’s not a schism, maybe, but two poles: the Kazakh-language side and the Russian-language one. And the work of authors who exist on one or the other side doesn’t always make it to people who might like to know what’s happening in our country’s literary scene.

With my publishing work I want to be that point of contact: where Kazakh- and Russian-language readers can learn more about each other, and where Kazakh-language writers can bring their work to Russian-language audiences, and vice versa. For me, this is crucial. Someone told me, even, that this is less of a business concept as it is a scientific research proposal. I mean, if it is that, then let it be that—I myself am a Kazakh person who doesn’t fully speak her native tongue, and even from childhood this was a huge insecurity. I’ve felt guilty about this my whole life, even though I know that it’s a question of context, a question of the reasons why this kind of separation of cultural and linguistic spheres happened in our country. It’s our history, and we need to make it more harmonious, more natural to befriend each other. At the same time, we need to move in the direction of understanding ourselves and our language. To me, it seems that there isn’t enough of that kind of publishing, or enough of those kinds of organizations, that can bring those two sides together at the same table.

Books

Children’s books can be the foundation of our personalities, and of our self-determination. Not all of us get life experience from real life; books, especially good books, and their heroes allow us to absorb that experience from reading. We’re not just running to a fantasy world, as they say; we genuinely learn how to act in different situations. Understanding friendship, relatives, good relationships, what’s normal in society, and what’s marginalized—all comes from your understanding of the hero’s actions. Because in good books, like in good films, more often than not there aren’t just good or bad characters. It’s never simple, but that way it makes you think: Do you acknowledge what the character is doing? Would you do the same? If not, why? Why do you think it’s wrong? When you’re someone who is just beginning to form a relationship with the world, and starting to understand your own place in that world, children’s literature is a necessary basis for your development as a person.

Tentek

What even is a good book? A good book isn’t just an existing, printed book in a vacuum. It’s the result of a massive amount of work—not only on the part of the author and printer, but a decent-sized pool of other professionals, as well. For a good book to materialize, you need these professionals to come together and do it right. For that, you need publishing.

When I decided to open a children’s publishing house in Almaty, I thought a lot about the name, naturally. At first, I wanted to name it “Tentek zhurek” (original in Kazakh: Тентек жүрек, translation: “Naughty heart”) because in my song “Zhaik” there’s a line “Tentek zhurek—taza zhurek” (original in Kazakh: Тентек жүрек — таза жүрек, translation: “Naughty heart, pure heart”). But after thinking about it, I decided not to make it more difficult than it needed to be. I liked the word tentek. For me, it was always associated with the realm of children. In Kazakh-language families we have an erke (the favorite) and we have a tentek (the troublemaker). I felt like the word tentek was never really anything devious or naughty. I liked it because it was more like an imp: a little wild but in a good way, a childish way. As we get older, we internalize things and turn them into personal armor, but all those children that live within us, they’re still there, and I’d like for our readers—who are small, who are still tenteks, and the grown-ups, who have the tenteks within them somewhere still—to feel that inner child, that curiosity and openness to the world.

Support

Historically, every publishing house began with a person who wanted to produce books, and a person who had money. That was always the case in Europe, and in the U.S., as well. Later, it might become something bigger, but it always started with small stuff. But in Kazakhstan, it’s almost as if there isn’t a way in which we can work—not with the government, nor with private organizations—to get financial support. Why is that the case? I think it’s because we’re a country of bidding, and more often than not there is a government request on one or another book, and the one that wins is the one that is the easiest or most convenient, in most cases the one that can be done in the shortest possible time, and the quality suffers as a result. Well, and the fact that it’s all reviewed from one side, usually that of the requested organization and what they want.

In countries where book publishing is more developed as a business, big companies often provide support at the beginning, along with the government directly. In Kazakhstan we’re still looking for a way to set a precedent for the government, along with corporations and private investors, to see how important and interesting it would be to invest in this type of product. Because, at the end of the day, it’s really what we leave to future generations, and what will change the rules of the game in the book market.

As an initiative, we’re excited about any support from any organization with whose principles we agree. We’d like for not only private organizations and investors to be interested in the progress of literature, and that such progress not only be confined to a “year” of something—of children or children’s literature, and then fail to be sponsored after the year is up. We hope that it might exist beyond that, outside of dependence on the day-to-day, because we believe our work will leave big tracks in the development of our country. Not just the work of my publishing directly, but any organization that works to develop the culture of our country, its cultural society, and changes the principles of work—moving towards something better over the course of history.