We asked Eleanor Dare, a London-based artist and academic currently teaching at Cambridge University, to visit the new exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum. In the following piece for Adamdar/CA, Eleanor shares her reflections on the Saka culture, ancient symbols and meanings of East Kazakhstan, and on how it all connects with our contemporary world.

Gold of the Great Steppe is a major exhibition of artifacts from the Saka culture of Kazakhstan. The artifacts emanate from the burial mounds of elite Saka people of East Kazakhstan, from the burial complexes at Berel, Shilikty and Eleke Sazy. The many objects excavated from the mounds date from as far back as 2700 BC, demonstrating highly skilled artisanship and a deep understanding of materials, some of which come from many hundreds of kilometers away, implying networks of material culture familiar to many of us through the phenomenon of the Silk Roads. Numerous objects depict animals and plants as well as mythical creatures, suggesting a complex symbolism which the exhibition encourages visitors to engage with. The exhibition is hosted by the Fitzwilliam Museum in the British city of Cambridge, running from Tuesday 28th September 2021 to Sunday 30th January 2022. This is a major event, occupying two large rooms which take visitors on a journey through the rich symbolic landscape of the Saka culture.

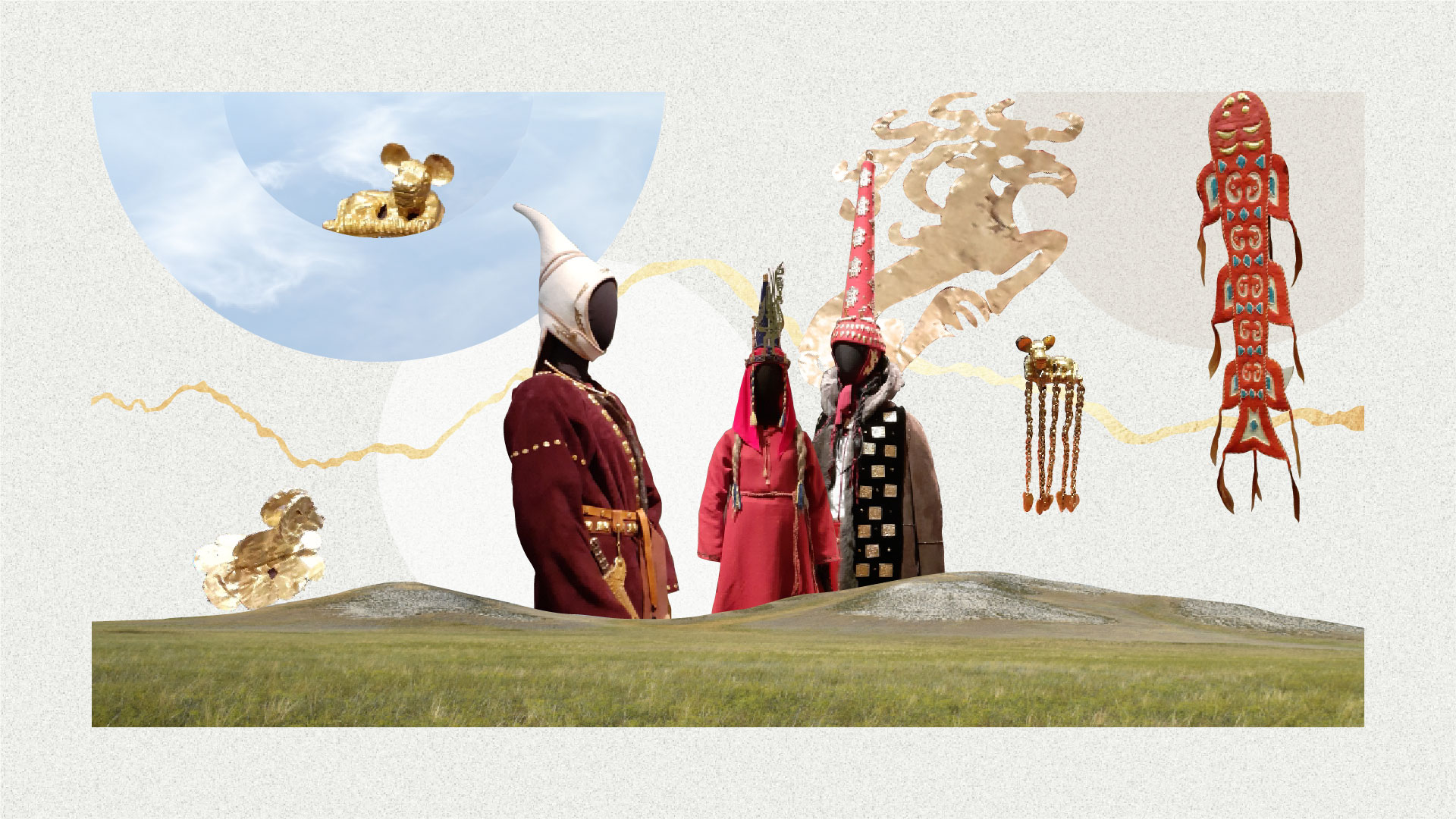

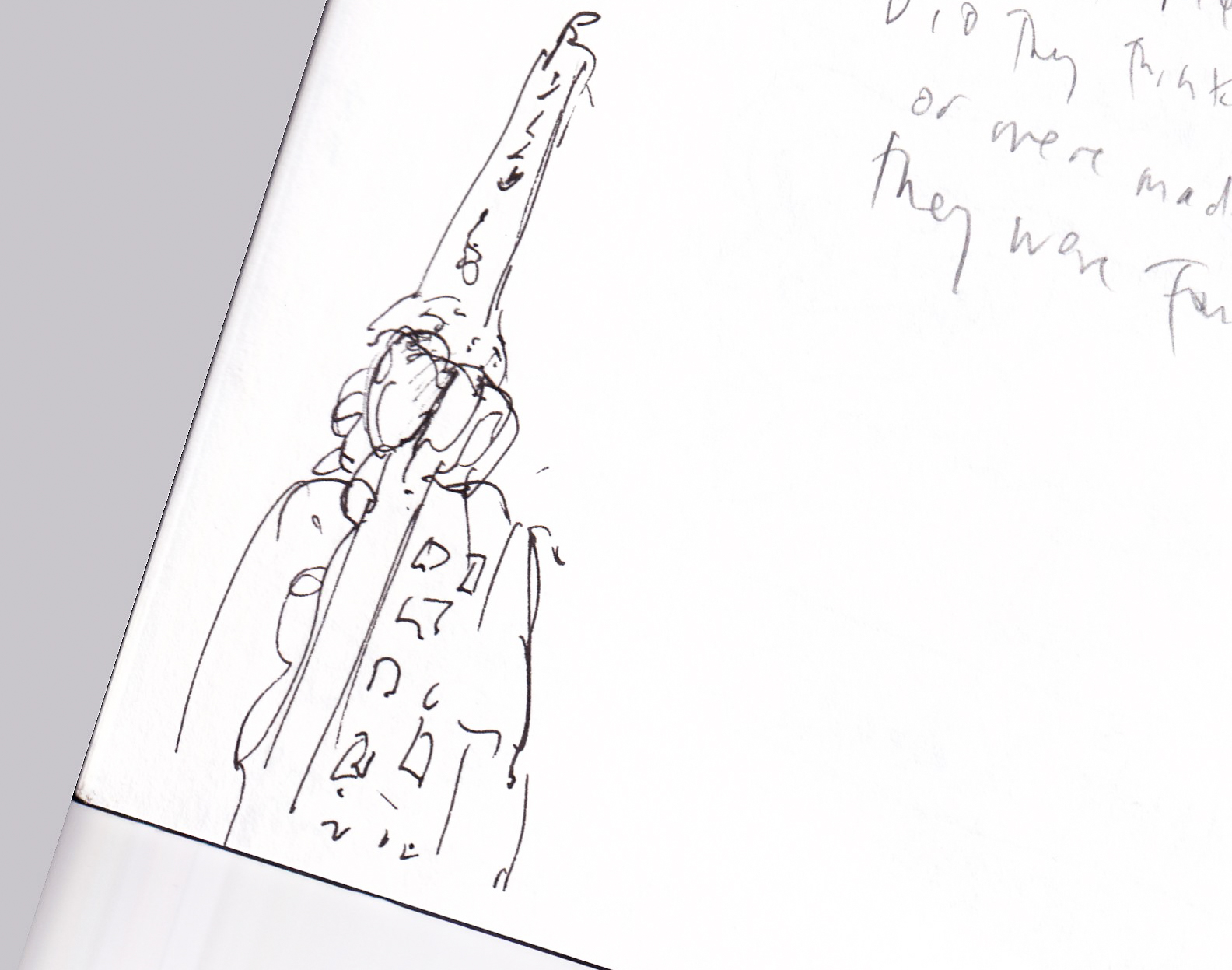

The first room is divided into thematic sections by very large landscape photographs evoking the scale of Kazakhstan, its vast mountain ranges and immense Steppe. Spaced throughout the exhibition are eerie manikins which show how the delicate gold objects might have been integrated into costume, their blank faces and high hats conjure something of the modern and ancient world, half robot or android, half magician or Shaman, with feathered hats and fur collars.

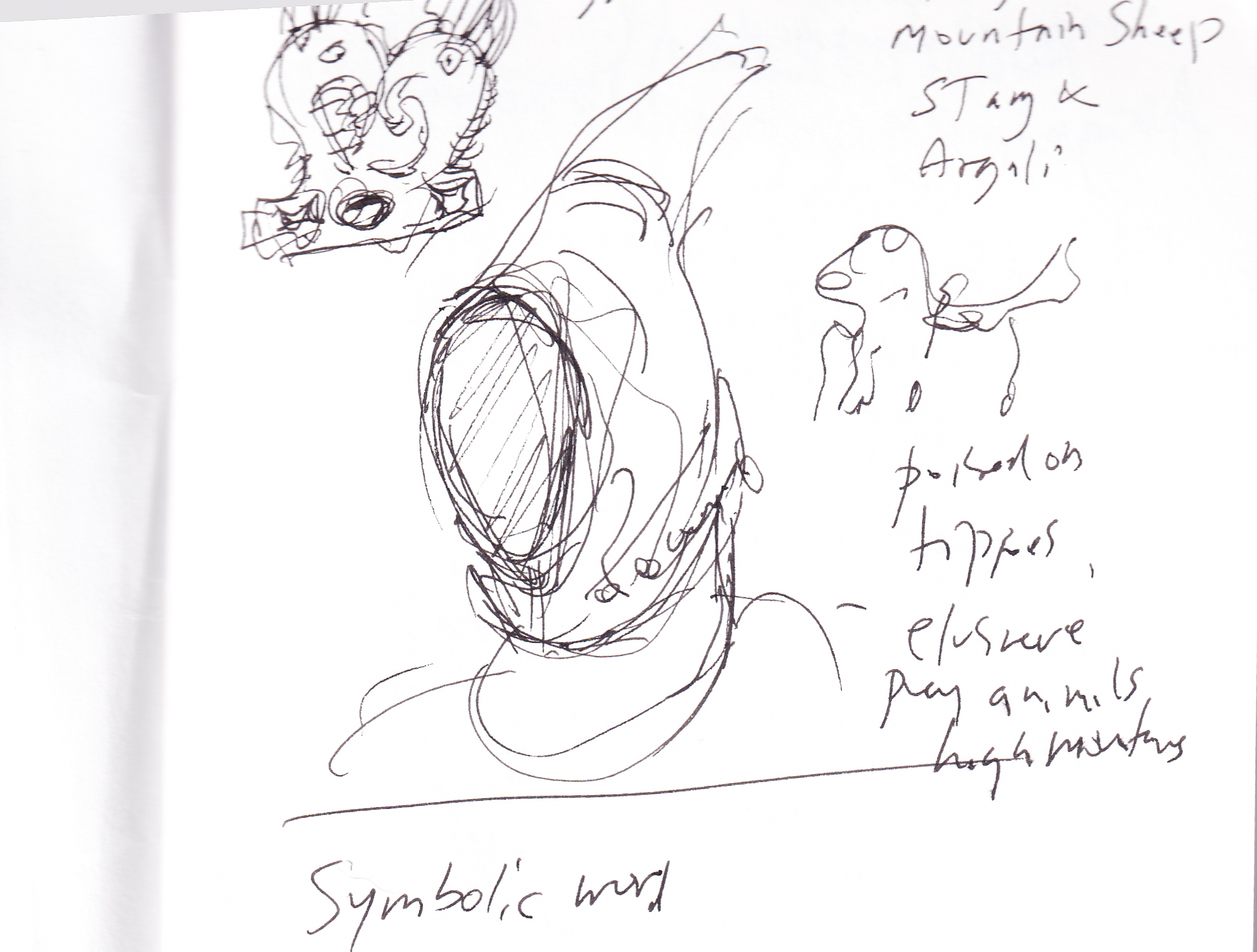

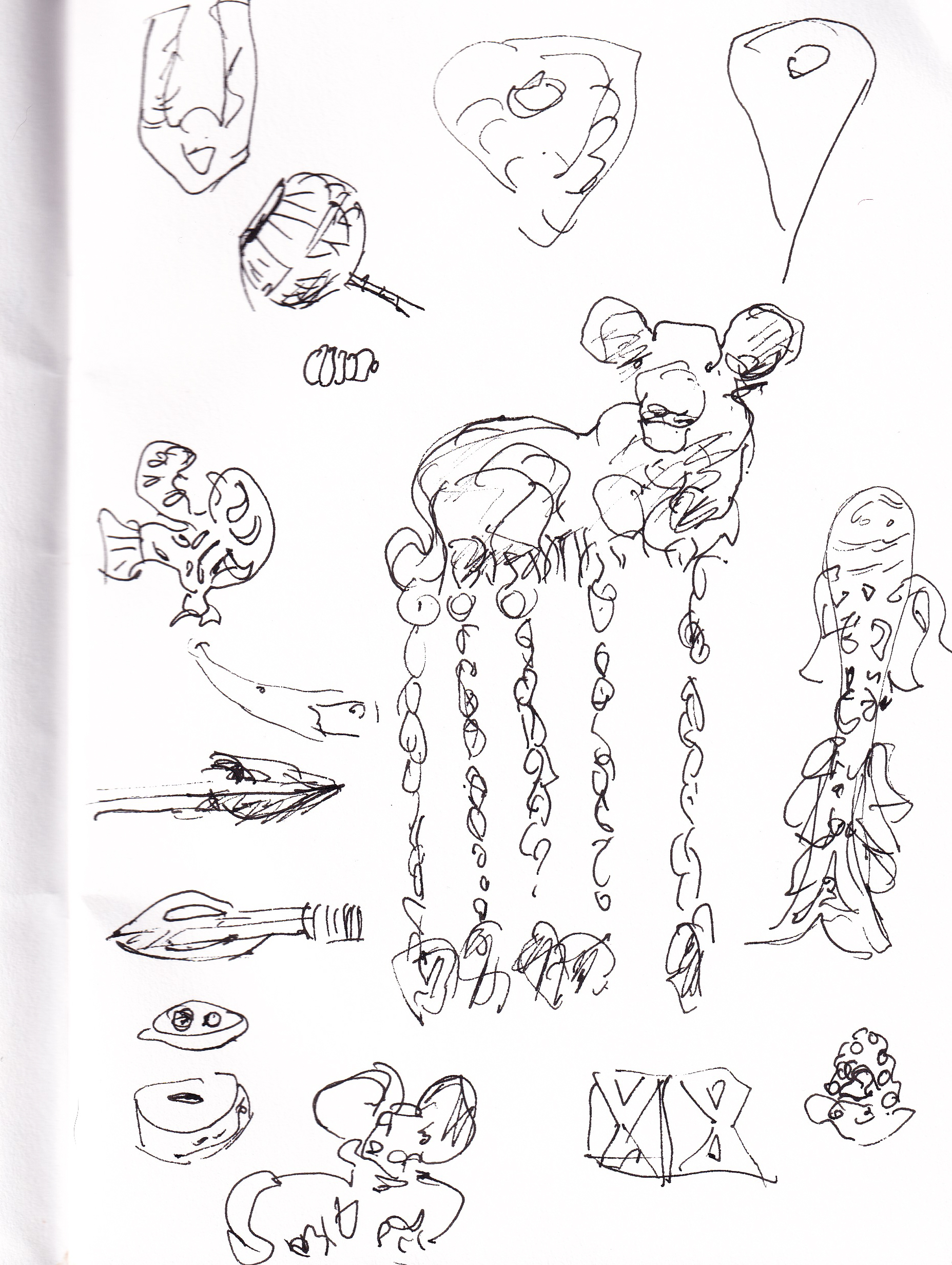

The frequent mixture of human and non-human animal symbols points to the ways in which humans and other animals are intimately entangled, in a culture whose artifacts and burial practices depict horses, argali (mountain sheep), birds, flowers, rams, deer, stag and hybrid creatures, such as hippogriffs, often in serial arrangements. On the exhibition walls a gold line suggests the Kazakh landscape and the passing of time, but also the longevity of social networks, which I was lucky enough to see something of as a co-investigator for the British Council Crafting Futures project in 2019 and 2020. Crafting Futures is a British Council and UKRI GCRF funded project addressing global threats to material and intangible craft practices and heritages. The Central Asian part of the project has entailed working with many different crafts people and researchers in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Much that is presented in Gold of the Great Steppe Exhibition resonates with the Crafting Futures project, not least the profoundly situated knowledge which many craftspeople bring to their practices. Time and time again we have encountered an understanding of craft as imbued with historical, cultural, spiritual and existential implications. Many of the craftspeople we have worked with identify craft as a manifestation of nomadic values, an ethics of human-animal and landscape relationality to which the world needs to pay urgent attention.

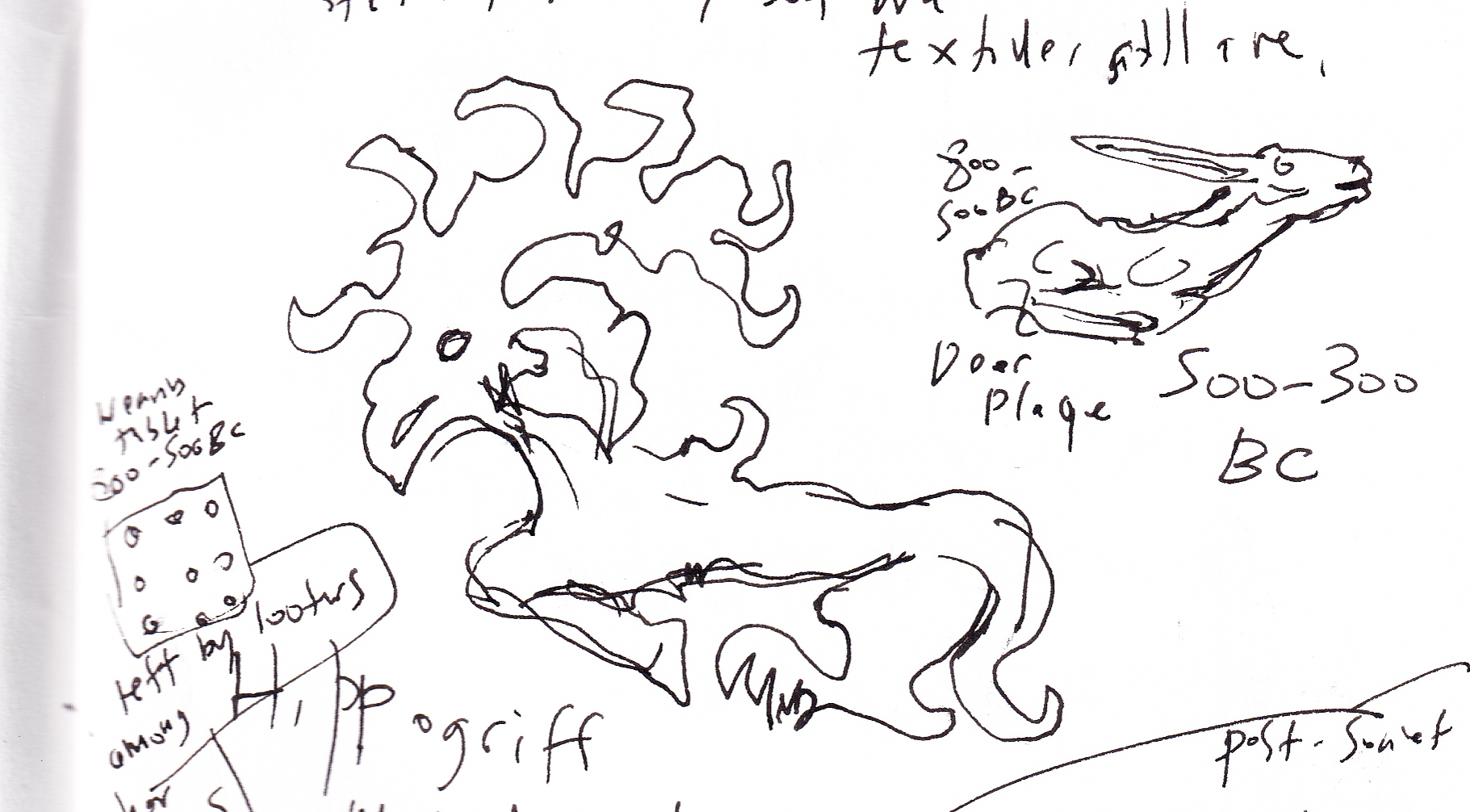

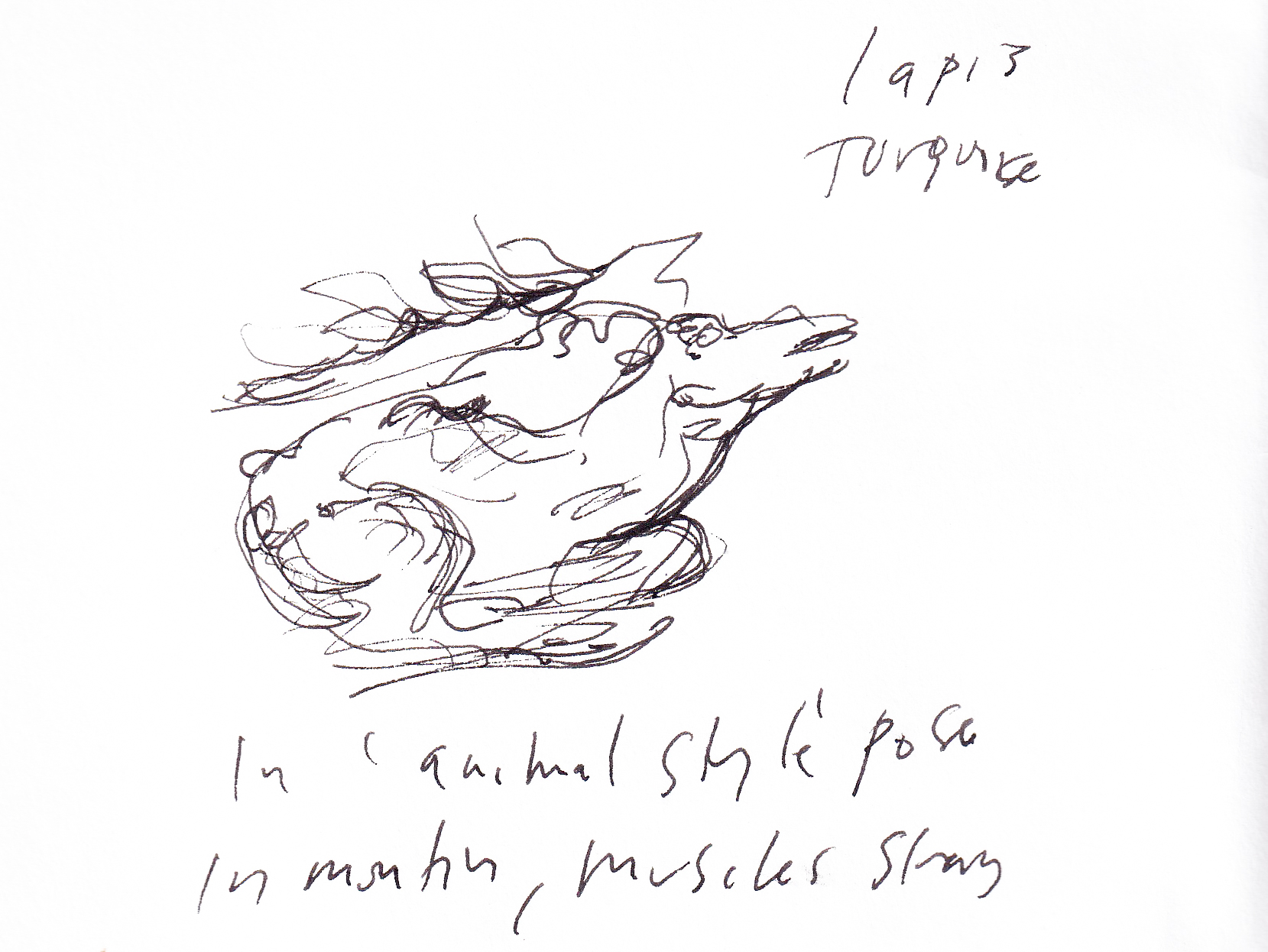

Just before visiting the exhibition, I was teaching a workshop on media analysis at Cambridge University’s Faculty of Education, looking at semiotic approaches to analyzing objects, or in other words, trying to understand the meaning of material and symbolic cultural artifacts. The students I was teaching were not much older than the Saka teenagers or ‘noble youngsters’ in the double burial consisting of an elite configuration at the Eleke Sazy burial ground. The girl in the burial was estimated to be 13 or 14 years old, the boy, 18. They were buried with seven gold plaques of deer and one stag, indicative, so the exhibition catalogues says, of a Saka deer ‘cult’. The deer are poised in muscular motion, or ‘animal style’, appearing both strong and delicate, with inlaid lapis from Siberia and Kazak Turquoise. Their meaning appears to be complex, intertwined with pragmatic and sacred implications beyond the importance of a food source, but speaking of our entanglement with other animals and materials.

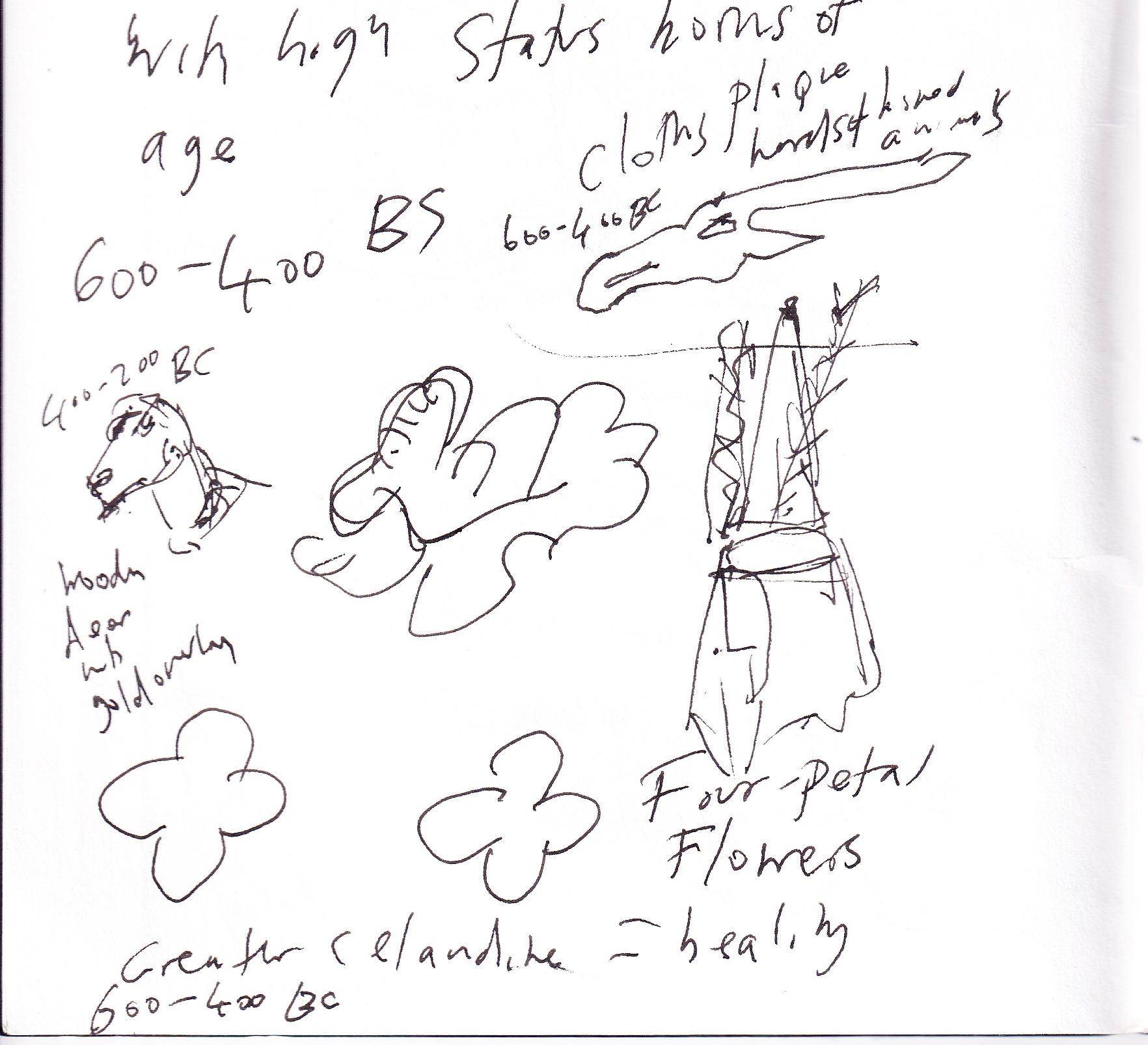

The exhibition and its handsome catalogue address the Saka tradition of burying horses with humans. One photo in the catalogue shows a tangle of bones in which the human is inseparable from the equine. The degree of effort put into the architecture and design of horse burials clearly points to their significance within elite Saka culture. Horses it seems, are often integral to the processes, practices and rituals surrounding death, but this is not an exhibition which leaves us with an impression of equine weight, rather of weightlessness. Gold of an almost buoyant lightness dominates this exhibition, evoking altitude and agility, a distinct relationship to gravity, one which sheep, horses and deer epitomize. Many objects depict deer and stag in motion, indeed, argali or mountain sheep made from fine gold are arranged on gold clouds, as if perched on top of mountains or in another realm of existence, an otherworldly domain. Other objects depict hybrid animals running on the tips of their toes, reinforcing the impression of lightness and speed.

The exhibition describes a ‘rich symbolic language’ while acknowledging that we project our own lives and concerns onto historic cultures. In this work we see a ‘deep connection to nature’ and a ‘sophisticated understanding of their spectacular environment’. In the lecture room at Cambridge, we were thinking about the choices designers have in making objects, and this question of course came back while looking at the many objects in this exhibition. Those choices tell us about any human-made object or idea, they tell us what matters to people, but with ancient objects we have to rely upon educated guesses and projection.

A family trail booklet encourages children to ask questions of the objects, to try and understand the people who made and owned these artefacts. It asks children to pay close attention to the way such objects might have been made, did they think the objects were made in proximity to where they were used or did they think they travelled as objects to reach their end location, to the places where they were found? My partner is an archeologist and agrees that these are the kinds of questions archeologists also bring to bear on material culture. We might also ask, were such objects made by the people who used them or made in a specialist workshop by expert craftspeople? What do objects symbolize and mean, why were they put into a burial mound, how were they last seen or handled by those who participated in the burial process? Archeologists, like the rest of us can only conjecture, albeit with the support of their knowledge and analytical approaches and inferences. Archaeologists such as Zainolla Samashev have worked for many years to excavate and catalogue the many thousands of objects found in the great burial mounds of East Kazakhstan, they have apparently used new technologies to analyse artifacts from settlements.

The mounds at Berel, Shilikty and Eleke Sazy seem to rise like spaceships over the immense landscape, and must have held enormous symbolic power, dominating the land for many miles, like Stone Henge in Great Britain, and occupying important locations and channels, as other burial mounds do, in for example, Sutton Hoo in the United Kingdom or the ship burials found throughout Scandinavia. Horses and ships are both potent symbols for many diverse cultures, representing mobility, power, skill, and aesthetic impact, not to speak of their sacred meanings. To be buried with horses and ships points to their value, as does the presence of burying gold objects with the dead. Of course, gold cannot feed or clothe us and can only represent a small part of daily life for Saka people, especially the less powerful. The second room shows querns, stones for grinding cereals or grains into flour, worn down by years of use, as well as spindle whorls for hand spinning of yarn, and what remains of felt saddles. Cloth and other organic materials do not generally preserve as well as metals, so much is missing from most burial mounds and one wonders who or what is not represented, precious metal objects which belonged to an elite class survive, arguably leaving us in the dark about the lives of less powerful people and less durable or high-status objects.

What are the relationships to contemporary identity and cultural concerns? Is it projecting too much to state that the Saka culture demonstrates an understanding of landscape, materials and locations which resonates with our contemporary situation? If only because we have allowed ourselves to lose such a connection on a scale which has brought us to disaster.