At an event about the state of freedom of speech in Kazakhstan, after the speakers had mentioned fear of speaking the truth several times, I asked: “But what are you afraid of?” The speakers didn’t give an answer, either because they couldn’t formulate one, or because their fear was so profound that it was frightening even to put it into words. This culture of fear of expressing one’s opinion is, perhaps, a deep-seated vestige of an era of mass political repression. We are afraid to be different, not to agree with one other, to have or express our own opinion. We sort of know about the consequences of this, but cannot always articulate for ourselves what they are.

Political repression is not only our history, but also part of our present.

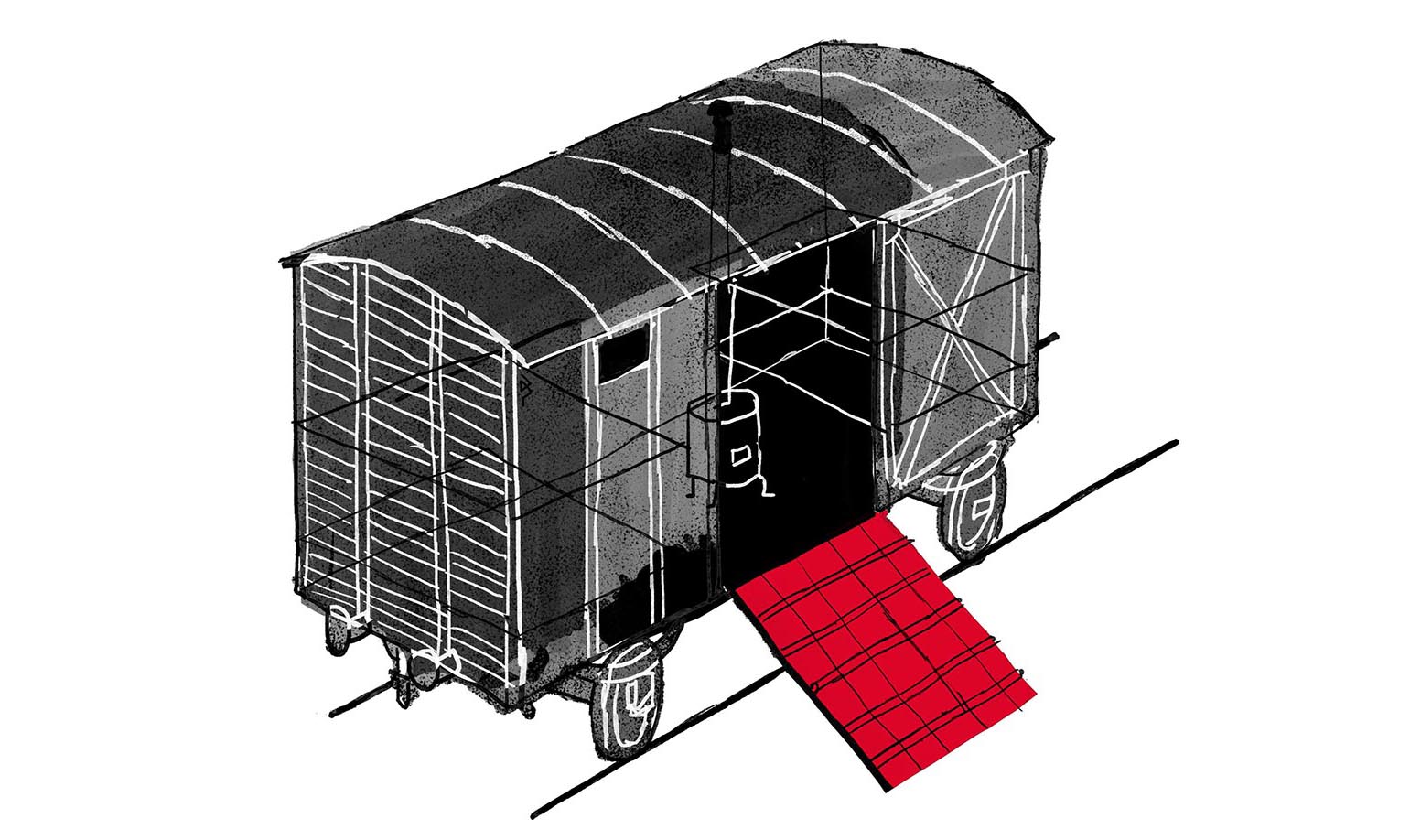

Political repression is a common thread in contemporary Kazakhstani history. The 1917 Revolution, the Civil War, “Little October,” Asharshylyk, the mass repressions of the 1930s, postwar repressions, the struggle for nonconformity and dissent in the second half of the 20th century—generation after generation of Kazakhstanis were born, lived, and many died along these historical lines. Our history, in this sense, reflects both the history of the USSR, of which Kazakhstan was a part, and, more broadly, that of the world. Those same 1930s, an apotheosis of famine and repression in quantitative terms, were a “blossoming” of political repression in the modern sense, and not only in our part of the world. From Falangist Spain to militaristic Japan, states pronounced whole categories of people enemies and cracked down on them in ways that were made possible by the unprecedented development of technology and the emergence of a massive state bureaucracy. In large part, it was the monstrous scale of that era’s human rights violations and the fear of repeating them that led to the formation and development of the modern international human rights system.

Why must we still remember the affairs of days past, risking, as some fear, giving rise to conflicts within society? Why shouldn’t we “turn the page,” “let the wound heal”?

In my view, there are three answers to this question.

First of all, we as a society still do not fully understand the extent of the effects of repression on what today’s Kazakhstan is politically, culturally, and socially. Millions of personal tragedies have not yet coalesced in our historical memory into a whole history of what took place. The same political culture we live in now carries a deep imprint of disrespect for nonconformity. A contagious culture of fear and cult of conformity have eaten into us so deeply that they are unconsciously passed from parents to children. At the same time, the ethnic composition of today’s Kazakhstan formed as a result of deportations and Asharshylyk.

Second, the memory of millions of victims of mass repression demands justice. When we speak about repression and famine, we are talking about murdered people, broken families, a destroyed way of life. In my opinion, the question about whether it is worthwhile to speak out about the experience of the millions of people who lost their lives, families, relatives, and property due to the actions of the state should not stand.

Third, and finally, the legacy of political repressions is still part of our reality. Today, without a doubt, there are no mass political repressions on the scale of 80 years ago, and it is unlikely that there will be; however, we still live in a paradigm of intolerance for nonconformity.

Aron Atabek, Max Bokaev, and other Kazakhstanis, whom part of civil society recognizes as political prisoners, are still in custody. Right now Alnur Ilyashev is under arrest, awaiting trial on charges of so-called dissemination of knowingly false information. There are articles in our criminal code about “the dissemination of knowingly false information” and “inciting hatred” that are the objects of criticism from human rights defenders and experts, who have drawn attention to the use of these articles to criminalize dissent. Thousands of peaceful Kazakhstanis were arrested in 2019 alone during peaceful protests. The provisions of the new law on peaceful assembly, which will go into effect quite soon, do not meet human rights compliance standards; in part, it excessively regulates what should not be regulated: the natural, autonomous freedom of people to gather peacefully and without weapons. The state is interfering in people’s autonomy and their right to join together—in parties, trade unions, and nongovernmental organizations. An overly complicated registration mechanism has been established for parties; this is complemented by reports in the media of unlawful obstruction of political groups’ meetings. The union situation has reached the point that the International Trade Union Confederation excluded Kazakhstan from its membership in 2018. The law stipulates mandatory registration for all nongovernmental organizations. The state even regulates freedom of creed and religion—all religious associations in the country are required to undergo a registration process and examination of their religious literature. People belonging to ethnic minorities, LGBT people, people living with HIV, and other “dissimilar” people frequently become victims of marginalization, hate speech, and physical violence.

In our country young women were sued for coming out for a peaceful march on March 8 in order to draw attention to women’s rights issues; activists walking peacefully with a banner calling for fair elections were placed under arrest for 15 days; even an artist who hung a sign with a quote from our own constitution was arrested. That is, the state as a mechanism still considers it necessary to spend its (our) resources on the persecution and punishment of peaceful dissent.

In this sense, the new law on peaceful assembly, unfortunately, could not break free from the logic that we have inherited, under which our natural freedoms can be subject to regulation, authorization, and approval. The state’s reluctance to witness public disagreement is a distortion of reality that has remained with us from the times of mass repression.

We are not the only society that has been forced to confront its cruel past. Let’s be fair—states and societies managed to spoil things for themselves considerably in the 20th century. But after the fall of the apartheid regime, the South African Republic underwent an extremely painful truth and reconciliation process; Latin American countries had to go through similar processes after the fall of military dictatorships; Eastern European countries did the same after the fall of communist regimes; and it is happening now in African countries. Often, this process occurs under the motto “Never Again” because remembering political repression—and understanding its significance and effects—is the most effective weapon against repeating it.

Discussing past mass repression will not devalue our past, and it will not stigmatize our ancestors or those whose ancestors participated in human rights violations. I myself am descended at the same time from a family that was victimized by repression and from a family that, by all appearances, did well for itself in that era. I think my story is typical for Kazakhstan. For me this is, above all, a conversation in which we must name and denounce repression. We must call things by their names and pronounce that political repression, persecution for nonconformity, and the suppression of civil liberties are bad and should not continue. Perhaps it is not as necessary to take the side of some political ideology as it is to affirm what is wrong and what is right.

A state commission on rehabilitating victims of political repression, the creation of which was announced on May 30, 2020, may be a step in the necessary direction, but it undoubtedly must not be limited solely to the rehabilitation of victims, but also fostering understanding of the reasons for mass human rights violations during the Great Famine and era of repression, as well as how to avoid repeating such tragedies in the future.

The period of the Great Famine and mass repression is one of the most important parts of our history, without which we cannot fully understand what is wrong with modernity and what needs to be changed. The contagious and toxic culture of fearing dissent—expressing one’s opinion, gathering peacefully, associating peacefully—made its debut there and continues now. The discussion of political repression is also a conversation about which characteristics our state possesses, which ones it should possess, and which ones we want to leave behind. Every time you are afraid to express your opinion or advise a loved one “bayqa” (Å: In Kazakh, “be careful”), you are reproducing the culture of fear in which generations of our ancestors lived and died, but in which we, and the Kazakhstanis who will come after us, absolutely must not.

Unfreedom cannot be a normal human condition.

About the author:

Rustam Kypshakbayev is a human rights expert and defender specializing in civil and political rights and the history of human rights. He is a consultant for the United Nations Office of Human Rights and a regional coordinator for the Center for Civil and Political Rights in Geneva. He graduated with a Master’s degree in Human Rights from the London School of Economics.

*The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Translated from Russian by Rachael Rosenberg.