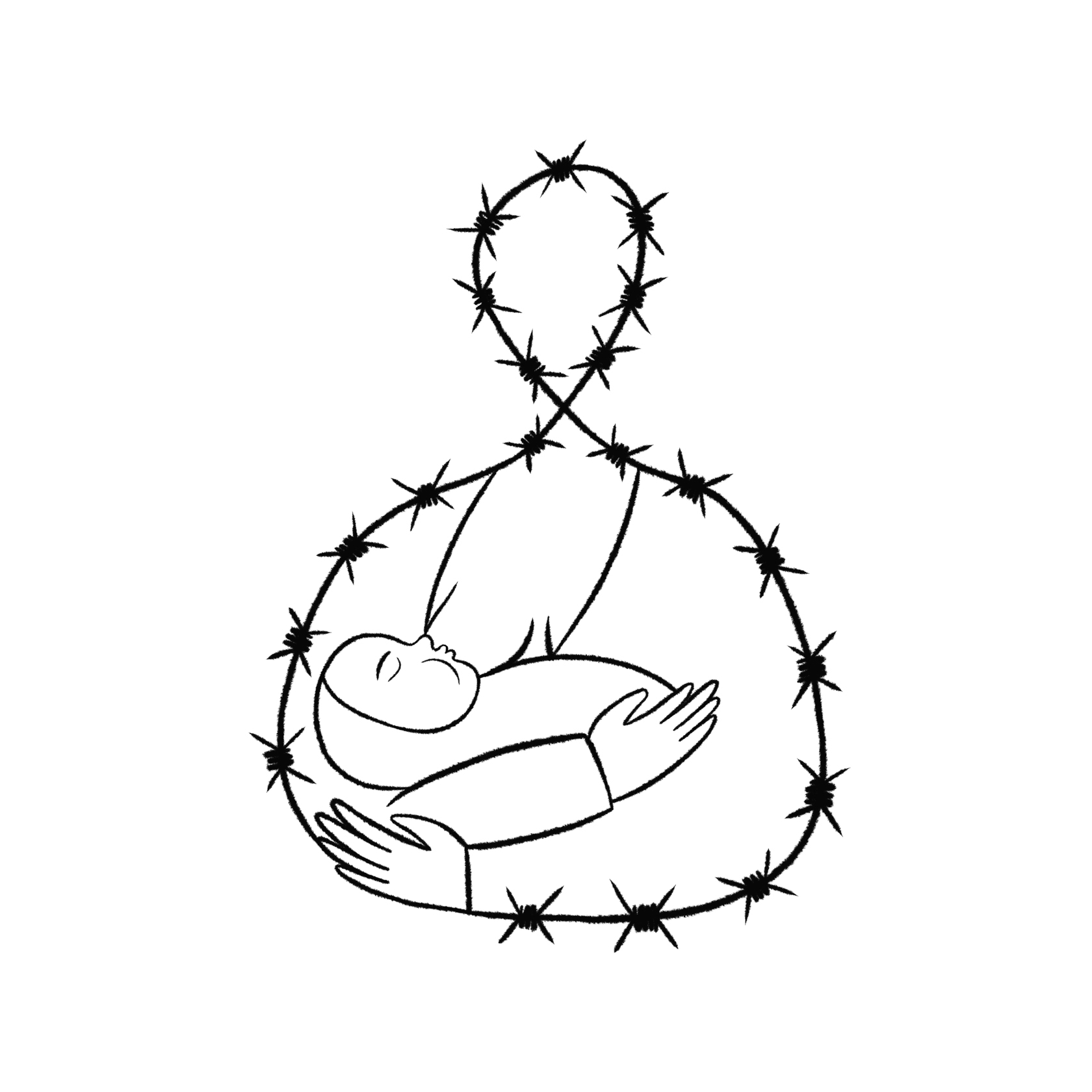

What is the connection between World War II and the current war in Ukraine? Between the Stalinist repressions of the '20s and ‘30s and the events of Bloody January, 2022? In her new essay, culturologist Zira Naurzbaeva discusses how collective trauma of the past and present influences the screenplay of modern Kazakhstanis’ lives, and considers strategies for overcoming these traumas.

The first trimester of 2022 brought many reasons for stress: living through what was happening in our country and then in Ukraine (with which Kazakhstanis couldn't help but identify), pain for the dead, fear of civil war and external invasion, fury for the lies spreading from official news and media, fear of economic crisis and hunger. In those January days, did you even consider the possibility of a severe food crisis? Did you regret not keeping weapons for self-defense in your home at any point? If not, perhaps this discussion isn't for you. If my nocturnal thoughts during those days–about how effective taping kitchen knives to hiking poles might be, or where to toss the flour bag–seem stupid to you, you're lucky. You weren't as triggered as me. Maybe it's the result of age, or family status. The maternal instinct and memories of the hungry years of the 1980s-1990s can't be wiped clean so easily.

Even still, I understand very well that the source of my deepest fears isn't my past experience or the events of this year. 2022 only activated the trauma that our ancestors were the recipients of over the course of the 20th century. Psycho(social) genetics is what scientists call the memory of stressors, the tragic (and/or positive) scenes that follow a person, and the actions taken to neutralize them. The most famous work on this topic is the book by Anne Ancelin-Schützenberger, The Ancestor Syndrome: Transgenerational Psychotherapy and the Hidden Links in the Family Tree. In Kazakh, psychogenetics is called tektanu, developed at home by Aliya Sagimbaeva and her scientists in the league of professional psychogeneticists of Kazakhstan.

But the topic of inherited trauma isn't discussed only by them. Reading the work of contemporary Western scientists, one can get lost—is this about history or psychology? The historical methodology about the Holocaust, for example, discusses topics like surviving history, a person inheriting trauma, the impossibility of surviving trauma or connecting with it, the return of trauma, melancholy. It says that a historian must not only feel the trauma, but simultaneously be able to work with it, manipulate, exorcize the trauma. One major theme of such work is that the border between past and present is not evidence in and of itself; rather, we must triumph, must ensure that the tragic events have in fact finished, away from us. Only then can we do something about them. Someone needs to set up a border to keep the past in the past, so that we can deal with the trauma and historical unfairness and begin living. Discussed and rehabilitated anachronism – the past, which hasn't passed on. As a result, we lose our historical perspective.

In the past, this research vein was mostly in the humanities, but today’s research in biology has shown that information about trauma, even without DNA mutations, is passed down to one’s descendants over the course of a few generations and can influence their lives (see, for example, this article). Thus, on the one hand, biology confirms what the humanities have been telling us. On the other hand, psychogeneticists say that we are able to change negative scenarios through disidentification (I myself can attest to the success of the method). The question we ask, then, is: Can subconscious work actually affect one’s genes? It would be interesting to see, from the perspective of biology, whether ancestral trauma that hasn't been worked out negatively affects one’s descendants. If you can work out the trauma you've inherited from your ancestors, you should be able to work out your own even more effectively–right? Modern psychology suggests a variety of instruments for this type of work, but as a culturologist, I'm more interested in the traditional ones. Did our ancestors work through their trauma? If so, how?

Among traditional methodologies comes to mind zhoktau (mourning). Zhoktau is the opportunity to demonstrate one’s grief for the deceased loudly and perceptibly and in a socially-acceptable way. Relatives of the deceased would improvise this demonstration within musical and poetic confines of the genre, and the best zhoktau would be preserved in the treasury of oral literature. The criers let down their hair, pushed against their legs, scratched their faces–in other words, indulged in behavior that was otherwise taboo in normal times. Zhoktau was done in the first few days after someone’s death, uninterruptedly and intensely until hoarseness, before slowly subsiding. After that, it would be heard for the last time at the memorial anniversary of the passing.

After the end of the memorial, a respected man would take down the funereal banner attached to the inside or outside of the deceased’s yurt, smash the flagpole, and burn it (cit. Altynsaryn). The women from the deceased’s family could resist and prevent the man from taking down the banner, thus demonstrating that they weren't yet ready to let go of the mourning period. In mythology, the banner streaming in the wind was the keeper of the soul, and the funereal banner–the keeper of the deceased’s soul. As such, the burning of the funereal banner symbolized the release of the deceased's soul (even if that wasn't acknowledged, especially during the Islamic period) and the ending of the mourning period. After this, the man would enter the yurt and thank the women performing zhoktau, letting them know that the mourning period was finished (this moment is shown in the film “Kunanbay”, screenplay written by kyushi and writer Talasbek Asemkulov). In this moment, we see an authority figure drawing a line between living with and through grief, between the past and present, formally allowing the family to return to their normal lives and to think about the future. Today, zhoktau is disappearing under the influence of Islam and modern upbringing, and is preserved in only a few regions.

It does seem likely that psychology, in the process of determining the different stages of grief, would be able to scientifically prove the therapeutic effect of zhoktau on people experiencing the loss of a loved one. There were also other rituals that allowed people to work through grief, including some on a more mass scale. Asemkulov tells how Kazakhs would designate abyz, people who would collect the community’s grief and then remove themselves, becoming hermits and playing the kobyz, “unweaving, unbraiding all the collected suffering” (lit. sher tarkatu). A portrayal of this type of recluse is shown in the stories of films like “Queen Tomyrys” and “Kunanbay”.

However, it was impossible in the 1920s and ‘30s to publicly show one’s grief over the golodomors (famines), civil war casualties, and Stalinist repressions. Such immense tragedies, which served as the foundation for the budding Soviet Kazakhstan, were not acknowledged or reflected on properly. Moreover, those tragedies weren’t mourned: they couldn't be demonstrated in either the traditional or new ways, because ideology demanded the exclusive projection of joy for the successes of socialism. Soviet power was not only the reason for the mass catastrophe, but also prohibited the acknowledgement and remembrance of it, dooming Kazakhs (along with other Soviet peoples) to the impossibility of working through that trauma. This resulted in the inability of the collective consciousness to convince themselves that the tragic events had really ended, and that it was possible to move on and live on with a full spectrum of emotions.

Some of this grief was sublimated in the mourning of losses from World War II, some in the fear of war, and the rest–whatever way one could. Talasbek Asemkulov begins his final article “The Fire of Conscience,” published May 01, 2014, by discussing how, in the 1960s, village Kazakhs adored Indian films. Entire villages would wail while watching. As one elderly woman explained, “What haven't we Kazakhs experienced lately! Grief recognizes grief. The majority of us sitting here are stricken by suffering,” (orig. shermende, tesik ukpe—lit. “despondent, as if with perforated lungs”).

Talking with young Kazakh intellectuals, the topic of which national symbols might help express grief, celebrate mourning, often comes up. What else, besides zhety shelpek and commemorative prayer? Something else public, and bright? These days, not every woman sings zhoktau. Burning candles came to us from Christianity, though there is the Kazakh concept of shyraghyn ushpesin (“May your light never go out”). At a memorial for Bloody January, the artist Denis Stadnichuk put on a performance with apples numbering the dead. It was appreciated, but the apple is really more of a woman’s symbol, anyways.

Psychogenetics demonstrates that historical tragedies of the past century can (and do) influence the lives of modern Kazakhstanis. These influences manifest in different ways, in scientific literature and in creative works, but they still aren't a fact of mass consciousness, torn away by the collective subconscious. As a result, the pain remains incredibly sharp, causing panic attacks and discomfort. It's not just a result of the 70-year ban on discussing the subject, either. Our traditional worldview lacked a framework for understanding how to survive mass murder at the hands of our government. One rare occurrence, in which a national tragedy was “worked through” traditionally, was the repression against the elites of the Adai, the cruel suppression of the rebellion, and exodus of the Adai from Mangystau. Traditional works and legends were written about those events, in which an external enemy–the Soviet government–ultimately triumphed, but the Adai resisted with honor. In the oral histories, there's a particular emphasis on the heroism of the Adai warriors, who fought so the villages (auls) could escape, despite huge losses, through the bullet fire of the Chekist anti-retreat units, and the eventual return of the Adai people to the peninsula during World War II–in their own way, a peaceful reconquest.

In and of itself, the defeat was a typical outcome in the tumultuous history of our ancestors. A framework for reckoning with that type of event was worked out: the pain of defeat, heroism of the warriors, killed on the field of battle with honor, the nobility and fidelity of women able to protect the descendants and preserve the lineage, the yearning for one’s homeland. There is also the life-affirming phrase, orynda bar onalar, or he who survives–recovers: we returned to the land of our ancestors. The Adai worked through their trauma this way, and continue to work through the pain of Zhanaozen. And the spirit remains unbroken.

In his autobiographical novel Midday, writing about his time studying with the elders, Asemkulov depicts the following scene. The elders, who have been sitting at dastarkhan all night, remembering friends who died in the golodomor or labor camps, leave the house and hear the sounds of young people celebrating.

“From the banks of the river was heard joyful laughter and the sounds of the dombra.

– Seems the party is in full swing, – remarked Sabyt.

– It’s their time now, – said Sherim. – They don't value anything. Jokes, laughter…do they know that beneath their feet are the shining eyes of Ilapi? Do they know that right there, on that bank, Bekey dug a fireplace?

Sabyt inhaled deeply. – It’s all unnecessary, Sherim. If youthful joy is futile, then Bekey’s fireplace digging would also be in vain. Why is it their fault that they were born at this time? Thank god life was not interrupted.

Sherim didn't argue, and looked with respectful eyes at Sabyt. They stood all four in the impenetrable darkness under the blessed rain, taking in the celebration of youth.”