Erlan Jagiparov was a businessman, a volunteer archeologist, and a member of a campaign dedicated to defending historical monuments at the site of Arkharly. Jagiparov was killed by security forces on January 06 in Almaty during the events of Qandy Qańtar (Qaz. — “Bloody January”).

Writer and culturologist Zira Nauryzbay, who knew him personally, even participated in archeological expeditions with him, shared memories of her friend and the tragic days of January 2022. The full version of Zira Nauryzbay’s story can be found in the text. A shorter version, voiced by the author herself, is available in a documentary animated film.

TW: The following material contains descriptions of inhumane treatment. If you have reason to believe that the description of violent scenes might be a trigger for you, please read and watch with caution or forgo any engagement altogether.

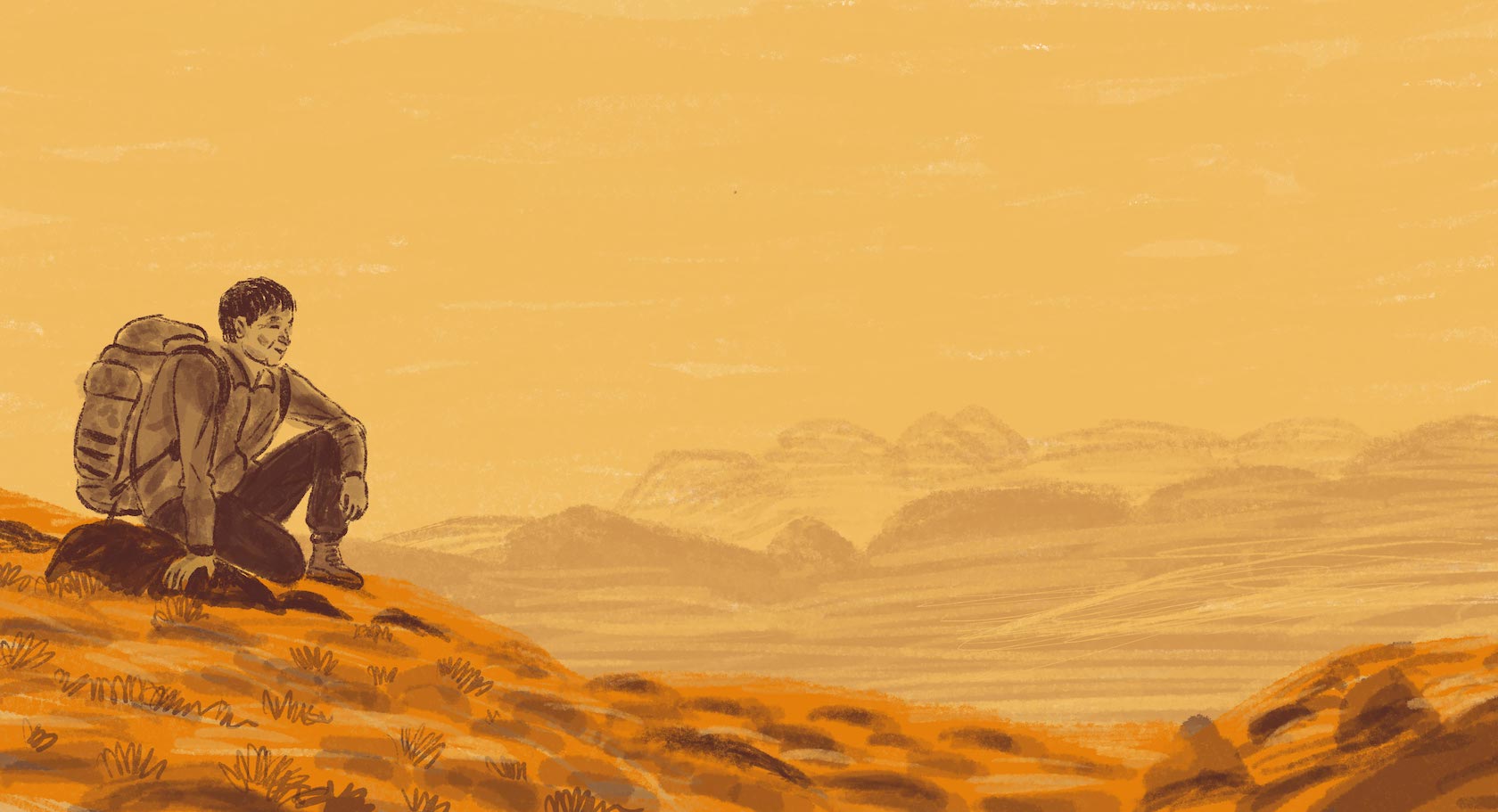

In today’s overwhelming age of information, it’s difficult to know what’s actually happening. But there is (as there’s always been) at least one dependable criterion: personal experience. For me, Qańtar (Qazaq; “January”) is the tragic death of our comrade from “Petroglyph Hunters,” a team of volunteer archeologists—Erlan Jagiparov.

On January 06, the captain of “Petroglyph Hunters”, Olga Gumirova, called and asked me, worriedly, how I was doing. At the time, I was at home in Astana with my family; we were all sick, probably with Omicron, but it was relatively mild. Since that morning, Olga had had a strong premonition and she reached out to her friends and the other team members as soon as she got cell service. The next day it came out that, around 7 p.m. on January 06, near Republic Square, Erlan Jagiparov had been arrested and taken away. He was able to get through to a friend and let them know that he was being held by National Guard soldiers. Through the phone, you could hear he was being beaten—despite the fact that he had documentation, proof that he lived at Samal-2, near the square. His friend listened as Erlan tried to reason with the soldiers, saying over and over, “Guys, we [all] are Kazakhs here, we’re Kazakhs”. A man snatched the phone from Erlan and, swearing, yelled stuff like: “All of you come here to the square, I’ll show you”. After some time, Erlan’s phone was switched off.

Click on ⚙️ for English subtitles

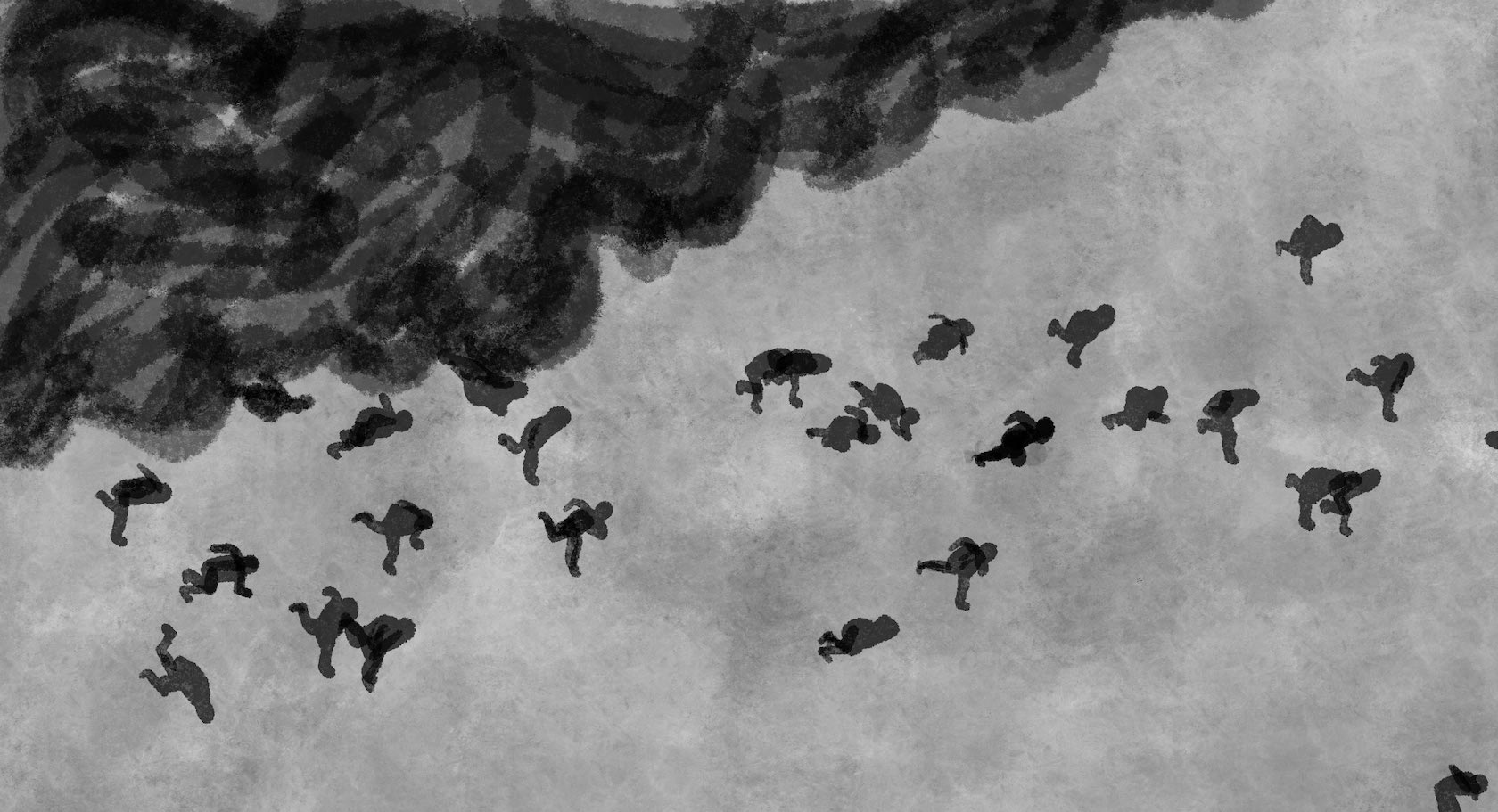

When I learned about the disappearance of Erlan, the pain and fear of those days—for the fate of the country, for the peaceful protestors—opened the floodgates. Having experienced so many losses, I thought that I couldn’t cry like that anymore…But the tears came and came. On January 11, after four days of searching, Erlan’s body was found in the morgue. The body showed evidence of severe beatings and gunshot wounds from Kalashnikovs. Detained, handcuffed, the cops beat and shot him. His death would’ve been easier to take if he had caught a stray bullet, like so many others during those days. Or killed in a fight, even. But he was tortured and killed with his hands bound by those sworn to protect the freedom and rights of the people. At that point, we already knew about the terrifying events our country had gone through, and the tears came again. No sobbing, just tears.

I went to Almaty for the 40 day-memorial of Erlan. His relatives came up to us, the Petroglyph Hunters, and thanked us for being there. I had only been on expeditions with Erlan two or three times (I live far away, in Astana); he would be up front with our captain, Olga Gumirova, who was navigating, while the rest of us in the back seat dozed off or chatted. During the expeditions, everyone would be scrambling about on their own, so I didn’t get to know Erlan that well. But he surprised me with his inexhaustible curiosity: specifically, his love for knowledge and his persistence, especially when he was questioning Olga or professional archeologists about the nuances of discovered ancient drawings. He was never flustered or tried to hide his ignorance, peppering the archeologists with questions—like a curious child.

It was only during the memorial that I learned Erlan was much older than I had thought: 50 years old. As a child, he dreamed of becoming a historian, but his father was determined that he pursue a more “masculine” career, so Erlan became a builder, owning his own small construction company. But well into his forties, via an ad he found on Facebook (where he went by his nickname, Erlan Stepnyak), Erlan joined a national archeological expedition in Issyk, organized by the sons of famed archeologist Beken Nurmukhanbetov, Arman and Bekbol, in honor of the one-year anniversary of their father’s passing. Through Arman, Erlan was introduced to the writer, journalist, and archeology-lover Olga Gumirova: who, carrying on the duties of her deceased teacher, the academic A. N. Maryashev, gathered together a group of volunteers. Erlan was thus able to fulfill his childhood dream, becoming the most active hunter of petroglyphs in the group.

On January 06, Olga had tried calling Erlan more than anyone else. She had a feeling that, out of all she was sensing, the biggest danger was to him—because of his child-like sense of spontaneity, his sensitivity, his protector nature. But she couldn’t get through. She sent texts, none of which he answered. Arman Nurmukhanbetov was able to get him on the line, it seemed: he said that Erlan was at home, in Kamenka , and that he, Arman, had asked him not to go downtown that day. But Erlan’s mother was really sick and needed care, so, finishing his work, Erlan headed in—to Samal-2.

Olga knew Erlan best. They were always going out on expeditions together; in his obituary, she named him the heart and soul of the “Petroglyph Hunters” team. It’s not that simple to end up on a team of volunteer archeologists—not only to discover and protect rock drawings and other historical monuments, but also to communicate findings to professional archeologists. It’s not enough to be curious. You have to be in good shape, be able to dedicate whole days to being in the heat or the cold, scrambling about on cliffs and rock screes. You have to have a certain love for heritage, especially if you’re going to dedicate weekends to expeditions, leaving at 5-6 a.m. and returning at midnight, often paying for the SUV rental or gas out of your own pocket. You need to have integrity and you have to be dependable, because all sorts of situations can arise when you’re out on an expedition, and it’s not only nature or technology that will test your strength. Sometimes, the “Petroglyph Hunters” would bother local law enforcement or the town fat cats, like in Arkharly, when we stopped the work on a ballast quarry owned by region’s former akim with the help of social networks, local media, a deputy of parliament Janarbek Ashimjan, and others. And if the captain of the hunters called Erlan the heart and soul of the team…Well, it means he was a person you could rely on.

In 2020, missing the steppe while in lockdown, I wrote the article, “Time Machine or: Think Like an Ancient Person” about an expedition that took place in 2019. At the time, I wrote more about my experiences while on the expeditions, not really accentuating the role of Erlan, but now I want to reminisce on a few moments. We all traveled in one car on that trip, the expedition itself wasn’t particularly lucky, and I got the opportunity to see what kind of person Erlan was.

So, we set off with my kids and with sister Aisha, Olga, and Erlan, who picked us up in his offroad vehicle at 6 a.m. It turned out that he had barely slept all night, had some things to do, but whatever it was, it didn’t dampen his spirits or his readiness to spend the entire day behind the wheel. After his death, Olga told a story about how, in his younger years, Erlan fell asleep at the wheel on the Kapchagay highway. The car flipped, Erlan’s father was killed, and he himself received trauma to his neck vertebra. Since then, he’d lived with the guilt of his father’s death and suffered from insomnia the night before long trips. This highway that we were traveling on was especially difficult for him, and Olga tried to help him overcome those feelings.

We turned just before Taldykorgan and headed towards a temple that dated from 2-3,000 years before our time, which the Hunters had discovered relatively recently. In the distance, mushroom pickers were wandering around. Erlan watched them apprehensively; he thought we should wait until they left, taking care in the case that they saw what we were doing, and learned about the petroglyphs, which would lead to vandalism. At the time, that level of caution seemed unnecessary to me, but now I think that it was from a desire to protect the ancient temple, which had already suffered so much from us modern people. To that point, a ceiling piece had already been destroyed and turned into a garbage dump.

We wandered along the edge between two rocky exits, hoping to find drawings that had been missed during the last trip. Olga was busy with her camera recording groupings she had already seen but with different lighting. Erlan and I grabbed the bag of trash and threw it in the trunk. Soon enough the work was done, and we headed in the direction of a mass of cliffs on the horizon in search of drawings not yet known to science.

Suddenly, Erlan stopped the car and jumped out, with us right behind. It turned out the tire had been pierced, likely by one of the sharper rocks hidden in the grass. Erlan deftly changed the tire and we started to get into the car, only to realize that not just one tire had popped. But we didn’t have a replacement for the other. Back to the highway was another 10 kilometers, and back to Almaty was around 200, at least to the nearest chance for patching…and today was a weekend. All things considered, Erlan took it pretty well that two tires on his SUV had blown. Olga called Uncle Muratkhan, a local farmer who had talked to some scientists about the petroglyphs in Arkhaly a few years back. He took the scientists under his wing, hosting them and asking local herders in search of new information.

As we waited for the farmer, Erlan started to build a fire to brew tea. This seemed strange to me: we had thermoses with tea already made, the sun was scorching, the day was hot, and here’s Erlan building a fire. And he did it all the way, too. In the trunk, it turned out, he had an ax in a slipcover and a spade to dig a fire pit, camping dishes, and a durable metal tripod with a clasp for suspending a teapot or a kazan . My teenage son, who also loves building fires, aided Erlan enthusiastically.

When Uncle Muratkhan arrived to help, Erlan stabilized the car on the two wheels and the jack as best he could, tossing out the luggage board from the trunk. We realized later that he was doing this for us, so we could hide in the shade below. He warned us that we had to be careful inside the car, so as not to tip it over, and he headed out with our savior, Muratkhan, to the body shop. Olga and Aisha set out on foot to the cliffs in the distance, turning blue in the sultry haze on the horizon. I didn’t want to risk going with them: when you get heat stroke as a kid, you can’t be too active in the midday sun after that. My children also weren’t really geared up for a hike. The inside of the car was already hot, so we carefully pulled our sleeping pads out of the Toyota and under the luggage board. A cool breeze blew from under the car. How nice that Erlan had considered that, had looked out for us that way. My son dozed off, my daughter read a book, and I listened to the warbling of a lark…It was idyllic. We were just like earlier peoples, hiding from the sun under а wagon. After a while, my son got sick of the inactivity and set off to relight the extinguished fire.

Olga and Aisha returned after a few hours, having unearthed another cluster of petroglyphs. Erlan and Uncle Muratkhan brought back the patched tires. Everyone drank tea together, and we set off towards the city. I thought about how to offer delicately to split the costs of gas and tire repair to Erlan—I mean, usually all of us pooled together to pay the driver for his work, for the gas, etc. Of course, Erlan wouldn’t take any money: he went out on expeditions for his love of history and the steppe. The money wasn’t nothing, though, and I thought it would’ve been fair to split it between us. But I realized that I wasn’t going to be able to offer him any money—he wouldn’t take it, and might even get offended.

I often thought about that day. And, of course, about Erlan: dependable, thoughtful, quiet, ready to look after others and protect his teammates and the ancient temple, indifferent to the material things. Like us, he loved the steppe (not without reason did he take the nickname Steppe-nyak on Facebook). He loved his warrior-ancestors, and he himself was a real warrior-protector.

In January, mourning the loss, I asked my son, who was already 16 and had been on other trips with me, if he remembered Uncle Erlan. He remembered him, and the fire they built together. I think that for him—someone who had been without a father for 8 years at that point—it was an important feeling. Moreover, Erlan’s gestures, boyish enthusiasm, love for instruments and technology, care and dependability resembled my husband, the kuyshi , writer, and researcher Talas Asemkulov, somewhat. I realized this as I looked at a photo of Erlan that the “Petroglyph Hunters” had put in the chat after his death became known. The tears kept coming: tears for the victims of all those days, manifested in the figure of Erlan.

But Erlan wasn’t a victim—he was a fighter. In fact, I’m sure that they killed him because they couldn’t break him. I believe that, despite being in handcuffs and reeling from beatings, he accepted his death standing straight, looking his executioner in the eyes. And now he is under the stars, in the circle of ancestors, clasping the shoulders of comrades and dancing a war dance around an eternal flame. His spirit will guard the temple in Arkharly and care for his comrades, just as he did in life.

We will always remember Erlan and feel his presence near, especially on expeditions. That autumn, I found a huge slab in Ordakul with incredible drawings that had detached from the rock face and tumbled halfway down the cliff. The slab was resting under a standing rock some ways below, and between the slab and the earth was a gap. I crawled beneath, attempting to photograph the petroglyphs, and remembered how Erlan, a professional builder, had calculated and organized the lifting of a half-ton slab, earlier knocked down by gravel harvesters, up the hillside with the help of ropes and blocks. Erlan could have lifted the slab at Ordakul, he could’ve brought the Hunters on new expeditions, could’ve searched for petroglyphs, made fires, could’ve surprised the team by buying new equipment. Erlan’s younger brother, an IT specialist named Nurlan Jagiparov, now sponsors a national expedition for the examination and certification of monuments from Ordakul—the last discovery that Erlan was a part of. Ordakul turned out to be significantly richer in ancient drawings than the team had originally estimated.

There’s not enough Erlan—not for the “Petroglyph Hunters,” not for his mother, whom he loved so reverently, not enough for his daughter, his brother, his friends and relatives. During the 40-day memorial period, his relatives reminisced on how joyful and selfless he was, how he brought everyone together with his warmth and energy. Apparently, he was always telling his relatives about the expeditions and discoveries, too. His relatives credited the Hunters for his genuine happiness the past couple years, glowing from having found his true calling.

During Qańtar different people were killed: peaceful protestors, innocent bystanders, armed forces and, likely, criminals. Each of them carried with them an entire world, each of them is mourned by someone. They can’t just be names on a long list—we should know each of them: who they were, why they were there, why and how they were killed, and who’s responsible. To give memory to those who deserve it, to understand why Bloody January was possible, and to make sure that tragic events like Jeltoqsan 1986 and 2011 never happen again.

For me, Qańtar will always be our friend, Erlan Jagiparov.

The investigation identified his killer based on the bullets and, under the pressure of the evidence, he confessed. How many others fell by his hand—only investigation and time will prove. To those who stood nearby and witnessed Erlan’s execution: Why are you shouldering someone else’s sin? Tell the truth.

We’ll wait for a fair trial.

Photographs provided by members of the group “Petroglyph Hunters”

Photographs provided by members of the group “Petroglyph Hunters”

From the editors:

We’d like to express our gratitude to Nurlan Jagiparov, Olga Gumirova, and the archeologists, volunteers, and other members of the group “Petroglyph Hunters” for their consultation and help in the preparation of this project.

The team at Adamdar/CA wishes to express our deepest condolences to the families of those who died and suffered during Qandy Qańtar.

We stand in solidarity with all citizens of Kazakhstan, human rights defenders, and independent journalists calling for an investigation of the January events.