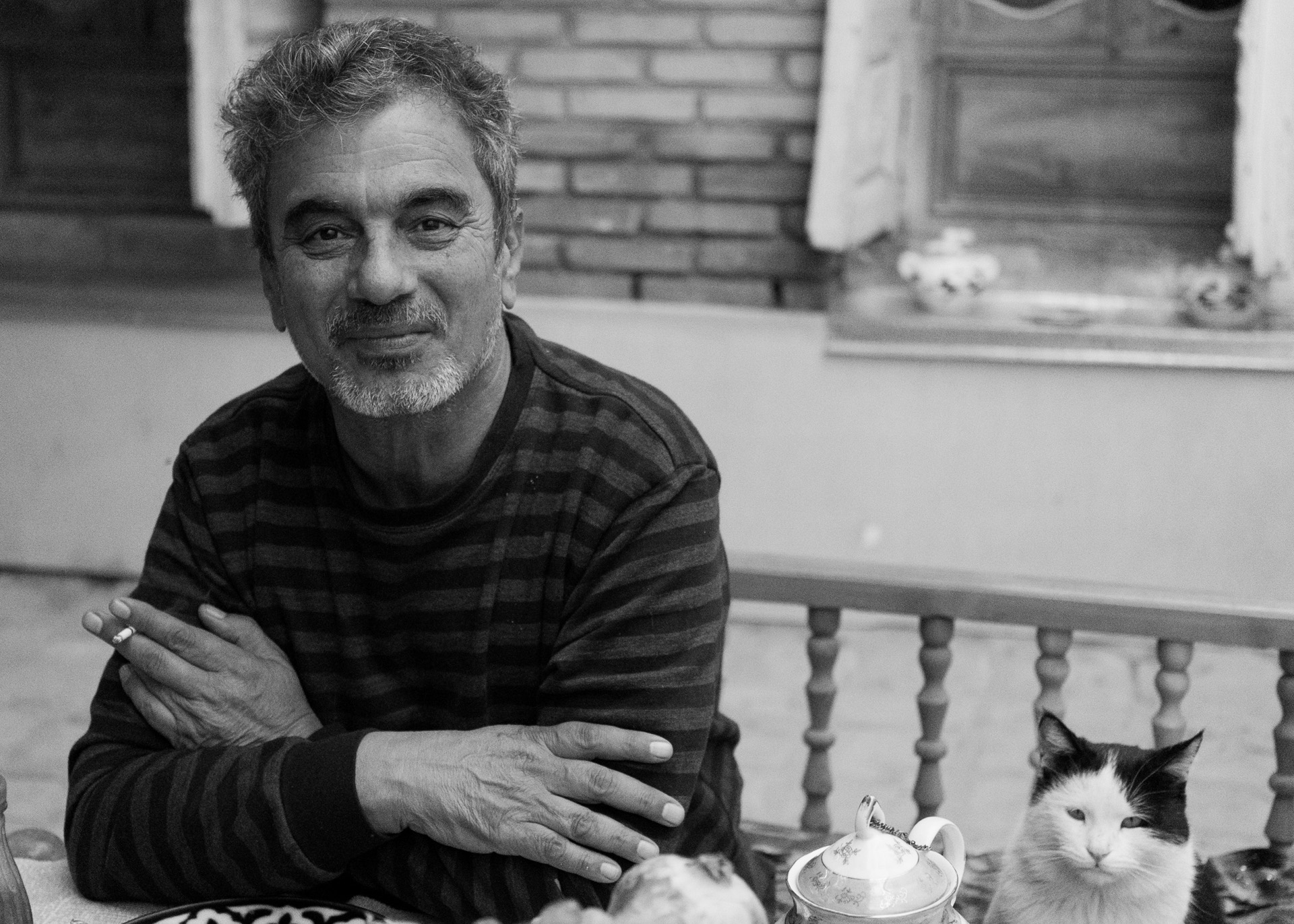

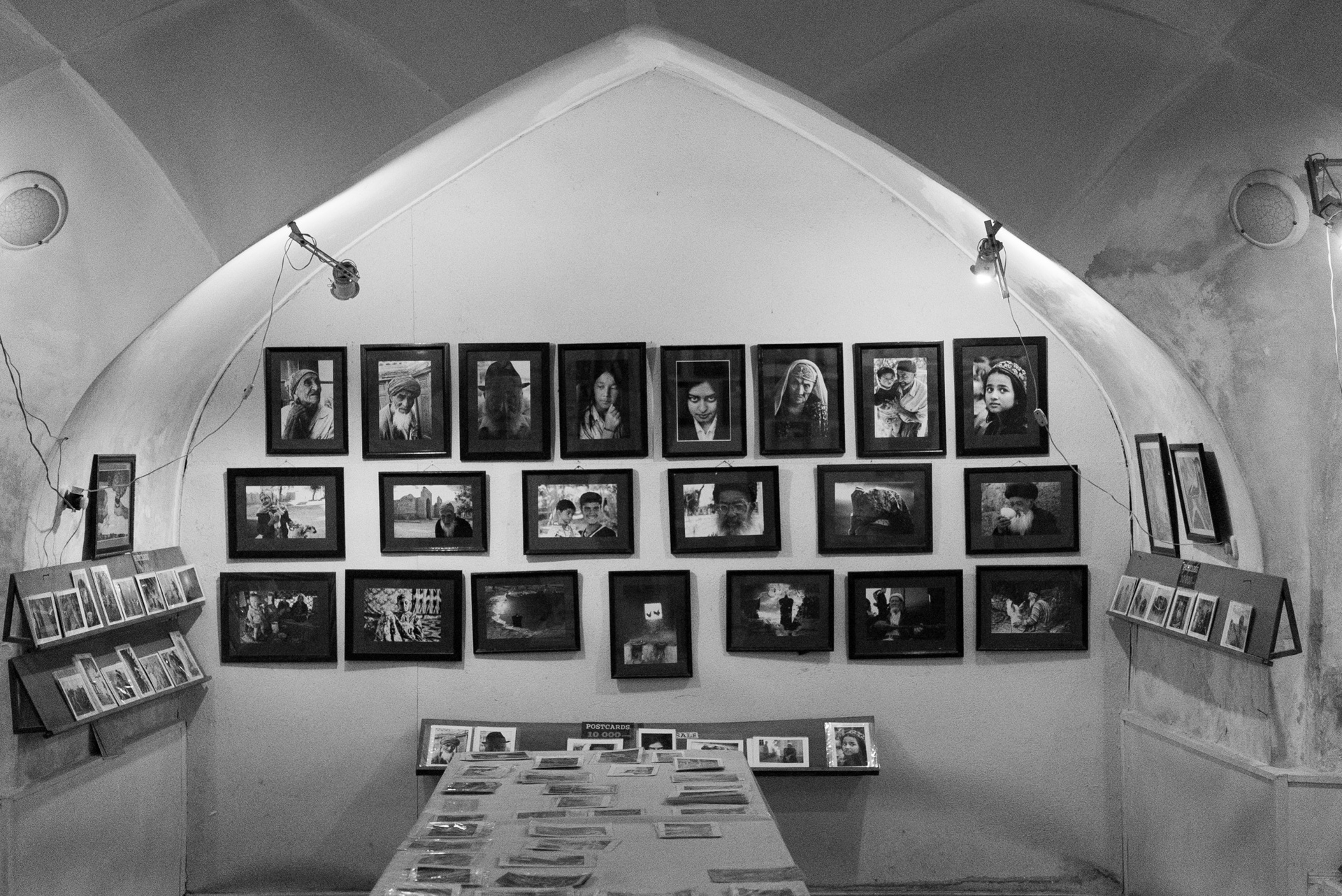

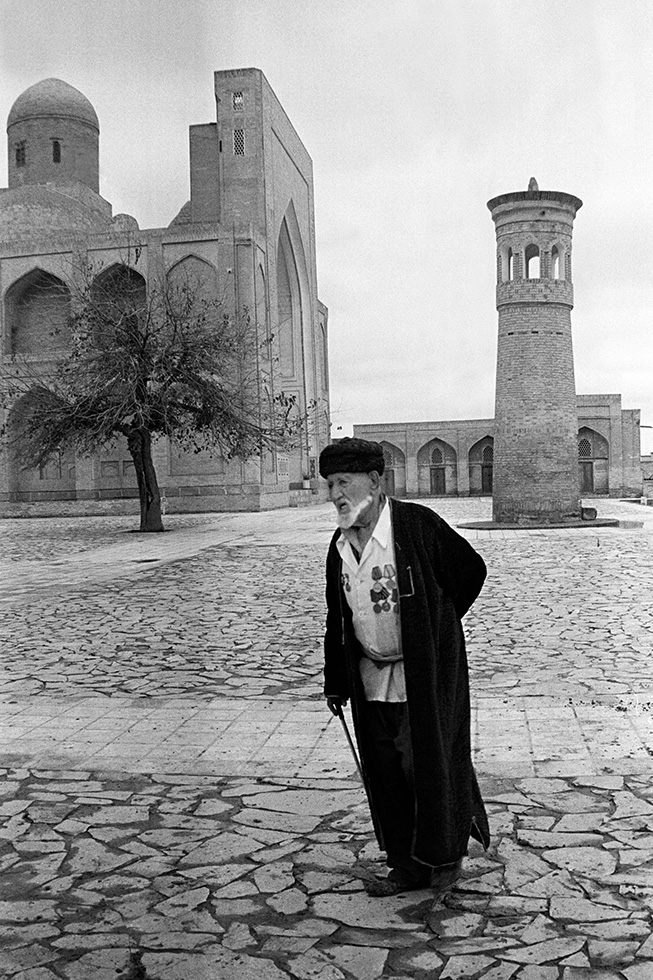

Shavkat Boltayev is a documentary photographer and artist from Uzbekistan. He’s the founder of the legendary Bukhara school of photography, a native Bukharan, and one of the main experts of both the past and the present of this ancient city. In the mid-1980s, he founded the first photo gallery in Bukhara. To this day, it remains a center of attraction for local residents and the many tourists who come to visit the ancient, exalted Bukhara from around the world.

BUKHARA

I am Shavkat Boltayev. I was born on January 20, 1957. I was born in Bukhara, I live in Bukhara, I create in Bukhara.

My paternal ancestors came here 300-400 years ago from Iran. From my mother’s side, I have Tajik ancestors; there is Afghan blood in me. We live in Uzbekistan, grew up in Uzbekistan. Our family is considered to be native Bukharan.

My father had ten children; his older brother had twelve. I myself have six children and ten grandchildren. I think that in total, our Boltayev family numbers a thousand people in Bukhara. Sometimes, when we have a wedding, we’re even afraid to invite everyone: there are just so many of us.

We speak Tajik at home and on the street. At school, we studied Uzbek and we know it well. We also know Russian well. In Bukhara and Samarkand, as a rule, all of our people speak three languages comfortably. Now, our children are learning English, French, Italian, Spanish, German. Hebrew is also taught very well.

Bukhara is situated at an amazing crossroads. On the right are Turkic-speaking Tashkent, Andijan, and Ferghana. Go a bit further and you’ll be in China among the Uighurs. On the left is Turkmenistan. Travel 700-750 kilometers further and you’re in Iran. Then you get into Afghanistan. From time immemorial, residents of Bukhara have mastered the languages surrounding them so communication would be easier with neighbors from all sides. Once upon a time, people in Bukhara also spoke Arabic, because Bukhara was a city of education and culture. The madrasas of Bukhara attracted the whole East.

Omar Khayyam lived in Bukhara for several years. In the village of Afshon, not far from Bukhara, the great Ibn Sina [Avicenna] was born.

I think it’s better for people to be friends, to visit each other. Ambition should be left aside: it will only cause conflict and misunderstanding. We must live in the moment.

My grandfathers and my father were coppersmiths, but then they switched to blacksmithing. I think Dad could speak to metal. He always said a person should be the best in his field at whatever they did. Once you achieved that, you could live fifty kilometers outside Bukhara, and people would come to you. In addition to blacksmithing, my father sang very well. He had a deep understanding of our maqom tradition*.

* Maqom (Maqam, mugham) is a generic name for various Eastern musical traditions. Shashmaqom (“six maqoms” in Persian) is a repertoire of six sets of instrumental and vocal pieces in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The Bukharan Shashmaqom is considered the “classic” Shashmaqom. In 2003, Shashmaqom was placed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

CINEMA

Under the Soviet Union we lived behind the Iron Curtain. Therefore, starting from the sixth grade, I began to choose a profession with which I could travel abroad. I looked at it this way: Becoming a diplomat wouldn’t work out. But I was very interested in everything related to creativity: cinema, music, books. I sorted through all my options and settled on cinema.

Many films were shot in Bukhara. After school, I loved going to the sets — they were enormous then! I would sit, watching and studying the goings on. After a day at school, I’d be hungry, but my curiosity superseded my need to eat. I was addicted. I decided then that I would definitely lead a life in the creative arts.

When I was 12-13 years old, a friend of mine from a music school showed me photographs that he made on his Smena*. He taught me how to use the camera, and together we began to shoot and develop our own photos.

* Smena is the name of a series of Soviet cameras produced from 1953-1991 in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg, Russia) and in Minsk (Belarus). Due to the simplicity of the device and its affordable price, Smena was one of the most popular cameras in the USSR.

One day, I approached my father, asking him to buy me a camera. The camera cost fifteen rubles, at that moment a significant amount for the family budget. Father said, “No, I promised to buy you a bike.” The bike was more expensive – fifty rubles, but he bought it for me. It was a good bike – an Orlyonok. About a month later, I’d had enough of riding. I suggested dad sell the bike, but he was against it.

I didn’t listen to my dad, took my bike, and went to the bazaar. At the market some musclehead came up to me and said: “How much?”

“Forty rubles,” I said.

“Here’s ten.” He took my bike and left.

I followed him for two kilometers, crying, asking him to give me the bike. And he, a muscled hulk, threatened me, and I was scared. I came home with those ten rubles and told everything to my mother. She gave me the remaining rubles, and I sprinted to buy a camera. My mom, sisters, and I all agreed that we would tell Dad that the camera cost 45 rubles. The camera was Smena 8M. It was so small and made out of lightweight plastic. For fifty rubles in those days I could have bought the Zenith model.

We settled this matter, and mom somehow explained everything to dad.

I was so happy. I would have given yet another bike to a muscled bully just to have this camera.

SCHOOL

There were two schools near our house. I was a naughty child, so my dad told my mother: we won’t take him to either of these schools. We’ll take him to one that is far away so that his teachers won’t complain to us. But this plan did not work. My teacher turned out to be our neighbor, so she stopped by our place anyway.

School was good; I studied very well. I wouldn’t let myself be bullied by my classmates. If anyone gave me grief, I’d respond even tougher.

The school was not elite. It was an ordinary eight-year primary school, but the teachers were highly educated people, some of whom went through the war. They did not let us relax for a minute: both in our behavior and in our studies. I even think that the threes we received [on a five-point grading scale] were better than fives students were receiving at any other schools.

So that after school I would not cause trouble and loaf around with hooligans, my dad immediately sent me to a music school. There, I studied the gidzhak*.

* The Gidzhak is a traditional Central Asian bowed string instrument.

I studied hard, figuring that music would be needed in the cinema. After primary school, I went to a music school. I also studied drawing and carving. I studied professions related to art only because I had decided that I would go into film. But my father had other plans — ones that didn’t quite coincide with mine. He wanted me, his youngest son, to stay with him and my mother. He worried that if he left our old house to my brothers, they would not preserve it. He thought that I, as a person engaged in the arts, should understand such things. In short, my father said: "Do whatever you want, but here."

I started teaching children at a music school. Meanwhile, I enrolled by correspondence in a graduate program in history, so that later I could return to the cinema. I got married, but my gaze was fixed on Moscow. I wanted to leave for the capital, go to VGIK [Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography]. I kept my correspondence with the VGIK selection committee secret from my father. And Dad watched me closely so I wouldn’t run away. He said: "Go ahead, run away, but then I will not give you my blessing."

Of course, even if I had run away, he still would have blessed me. But I was scared that I would hurt him.

It seems that when a person loves his aspirations, he will find a way to do what he loves. And at the end of the day, God rewarded me for following this path.

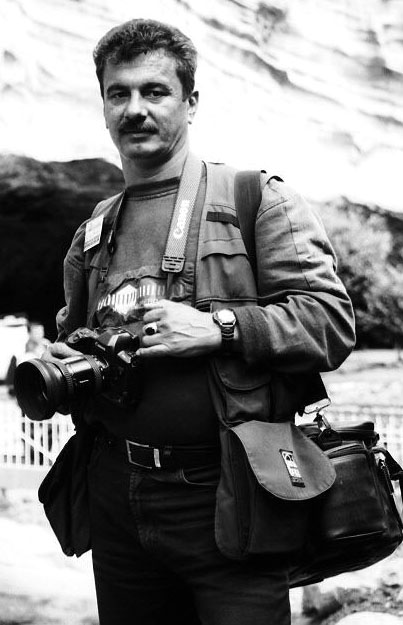

In addition to working at the music school, I opened my own photo studio in Bukhara. It was 1985. In those days, if you had an amateur photo studio, the state supplied cameras and films. We started shooting five to ten-minute short films, which we sent to festivals in Moscow and Leningrad. In this way, I began doing creative work intensively. I abandoned the music school, deciding to be fully engaged in the studio.

From the personal archive of Shavkat Boltayev

With time, a small photo gallery appeared. We began to sell our pictures. We’ve accumulated many over the past thirty years.

All film crews were sent to us because they knew that photographers know many things, shoot many photos, and they know the city like no one else.

Photo by Malika Autalipova

VYSOTSKY

Several years ago, here in Bukhara, I had a conversation with Vladimir Vysotsky’s son, Nikita, about his father. I told him everything I knew about his father’s historic visit to Bukhara.

At the music school, I had a friend named Markiel, a Bukharan Jew. He told me this story: It was 1979, and everyone was eagerly looking forward to Vysotsky’s concert. There were posters, show bills, and conversations everywhere.

It was eight o’clock in the morning. Markiel was waiting for his wife at the bazaar, who was buying something for lunch. Suddenly, Vysotsky came up to him.

“Hello.”

“Hello. Oy! Vladimir Semyonovich?!”

“Yes, it's really me. I have one question for you: Where can I get some plov?” [Central Asian pilaf made with rice, meat, and vegetables]

But back in those times no one was cooking plov that early in the morning.

Markiel responded, “Plov? At this hour? You can search the whole city and you won’t find it.”

“So. What should we do about this?”

Markiel said, “I have an idea. Stay here for ten minutes. I’ll bring my wife to work, then I’ll come back. We’ll go by motorcycle to my home. It is not far, 100 meters from here. And at home I will cook you plov, and in an hour you will eat it. Deal?”

“Deal!”

As soon as he got into his house, Markiel immediately began to call his friends: “Run over here pronto, Vysotsky’s in my house!”

They cooked a very good plov. Vysotsky ate and talked with them. A guitar was brought to him, he was treated to tea. And in the end, they all took a picture together.

Photo courtesy of Shavkat Boltayev

ENERGY

In the early 2000s, I began to get invited abroad. I visited more than forty countries of the world: the United States, England, France, Italy, Germany, Iran ... These countries are very powerful, good, beautiful. There I met immigrants from Bukhara. There are many of them, and they are very accomplished, but of course they miss our Bukhara very much.

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

Here in Bukhara, there is a special energy. I felt something similar in St. Petersburg and Iran. In Iran, it was as if I continued to be in Bukhara. And when I reminisce on St. Petersburg, there’s a good feeling in my soul. I managed to visit a piece of Kazakhstan, and I really liked it there, too.

If a person truly loves their profession, and doesn’t just say that they love it, then everything will work out.

Sometimes I think my father was right. I wouldn’t have been able to live in Moscow. It seems that my father did bless me after all because I was lucky. I worked with many filmmakers, starred in several episodic scenes. One time, I played myself: a photographer. I once even worked with Hollywood on a film about Omar Khayyam. The director was Iranian, so there was no language barrier between us.

If a person truly loves their profession, and doesn’t just say that they love it, then everything will work out, no matter where he is.

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

PROJECTS

I have two projects that I have been filming for over 20 years. When you shoot a project, you deeply research the topic so that you can delve into various nuances.

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

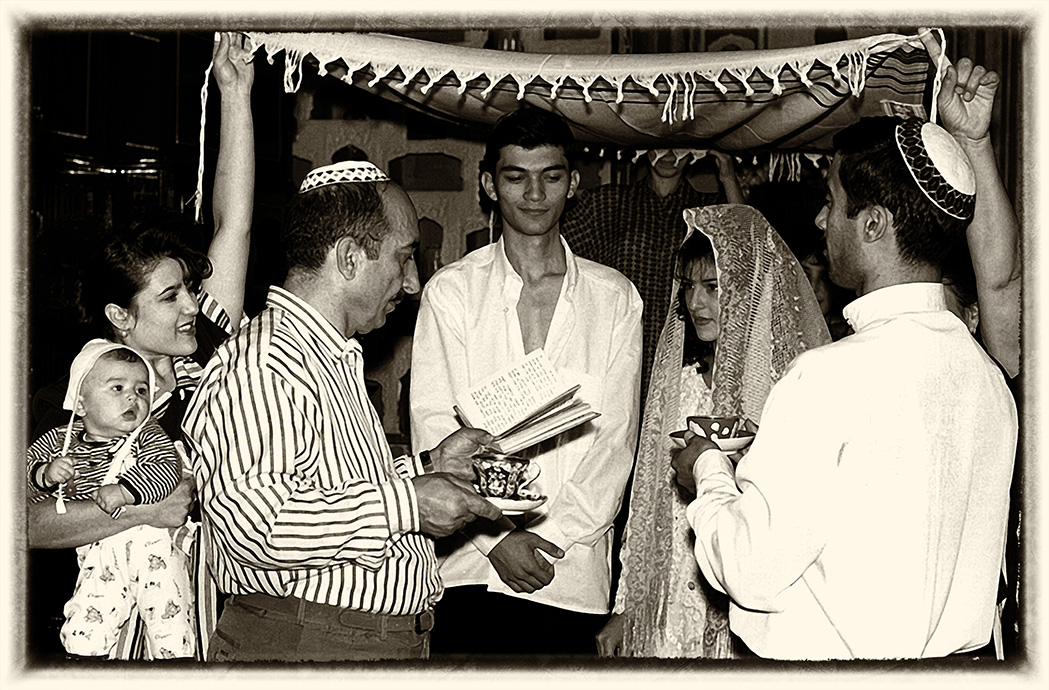

One of my projects is called “Life of Bukharan Jews.” Its other name is “The 21st Century: Bukhara without Bukharan Jews.” Most Bukharan Jews have moved to different countries of the world: Israel, Europe, and New York. In the 1970s, about 20,000 Jews lived in Bukhara. When I started my project in 1998, there were about 4,000 of them.

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

I started filming to show that the Jews are doing well. The Jewish Quarter with its synagogue is in the very center of Bukhara. I befriended the Jews, studied with them. But I guess a person goes where they know they’ll do well for themselves. Abroad, there is stability and good work that pays well. Bukharan Jews were especially frightened after 1991: they thought that there would be Islamization, and thus they began to leave. Now, there are about a hundred Jews left in Bukhara. Very few.

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

Once at a wedding, I saw gypsies and thought, why not take some photos of their community as well? In Bukhara, they are called Jughi. And in Uzbekistan they are called Lyuli. I devoted several years to them.

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

.jpg)

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

BUKHARA PHOTO SCHOOL

I love Uzbekistan. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are like brothers to us – I love them too. We grew up together. We went through difficulties together. I’m fond of Kyrgyzstan – it’s not called the "Island of Freedom" for nothing! I like that many cultural events are held there. There, business sponsors and supports artists. This astounded me. It’s fantastic! Uzbekistan still lacks that kind of support. But, of course, we hope for the best here. I was also in Georgia and witnessed the same thing: people are given a lot of opportunities.

I am a happy person here in Uzbekistan because I am the only photographer who has their own gallery. I created our Bukharan photo school.

We know every door, every brick

I have students from many different countries. It seems that I have made my dreams come true. In Tashkent, Bukharan photographers are very respected. It seems to me that photographers in Tashkent shoot in a European style. Meanwhile, we Bukharans explore our villages, yurts, and mountainous areas. We want to show our way of life, our national spirit. This is not because of nationalism or chauvinism. It’s simply because of the fact that no one knows our land and our people better than we do. We’re the ones who live here, after all. We know every door, every brick. And we need to show it to the whole world.

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

Author: Shavkat Boltayev

BUKHARCHIKI

Right outside of Bukhara, there is a cemetery of Germans, Japanese and Poles, who were prisoners here during the war years.

Once in 2009, two elderly couples walked into my gallery. They greeted me, speaking good Russian. They told me that during the war, in 1942, Poles were brought here. Adult men were taken to Navoï, 100 kilometers from Bukhara, and women and children were brought here. They lived here until 1946. My guests showed me a photograph of a Russian woman, a doctor who saved many Polish children.

These children who lived here in those years still call themselves Bukharchiki. They’re crazy about Bukhara, remembering that they survived here thanks to the kind people who would give their last morsel of bread to them. So now, they are coming here as if to Mecca. They come with children, grandchildren and they stop by my gallery.

This phenomenon interested me, so I made a project about it. It is called "Bukharchiki."

PROCESS

In 2008, my friends persuaded me to switch to a digital camera, a white Canon. Each person is different of course, but for me the transition from film to digital was painful. I envy those who have never worked on film. Film feels, film breathes. It seems to me that I still have not completely switched to digital. If there is a really special project, I’ll shoot it on film. My son also shoots on black-and-white film.

I’m not the biggest techie. When I give master classes, I tell my students, don’t ask me any technical questions. I don’t even use many of the functions on my camera. For me, the most important things are the process, the situation that I’m capturing, and its framing.

My favorite genre of art is photo documentary. A documentary photographer must be well-read. They should really be interested in their topic. These days, cameras are easily accessible. Budding photographers snap a frame or two and then they think they know everything there is to know about photography.

After I obtained my camera, I went to a hobby group that was run by a local Bukharan photographer, but there were no places left, so he couldn’t accept me. That’s fine. I started buying books and studying on my own. When I opened my own photo studio, I started going to festivals and exhibitions. I learned a lot from those.

Out of all photographers, I really love Henri Cartier Bresson, Sebastian Salgado, Robert Cap, Bruno Barbie, and Abbas. I met with [Gueorgui] Pinkhassov in Samarkand. [Yuri] Kozyrev was once my house guest. We took pictures together for five or six days.

On 9/11, I was in the United States, in New Jersey. People told me: "Go and shoot! You’ll be paid good money for those photos.” But I couldn’t take photos of the grief of strangers. I didn’t have the heart.

Central Asia is a bouquet. Different faces, different colors. And Bukhara is also like a bouquet: different populations, just like in a bouquet — there are red, yellow and other colors. We have Turkmens, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Russians, Iranians, Afghans, Chechens, Arabs – about 100 nationalities!

A few years ago, I started to paint. I paint with acrylic. It turns out that when you paint, emotions wash over you. The fate of the picture is completely in your hands. I'm still trying all sorts of genres, discovering my path, but I know that I want it to look childlike.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Adamdar / CA is grateful to Umida Akhmedova for her help in preparing the material.