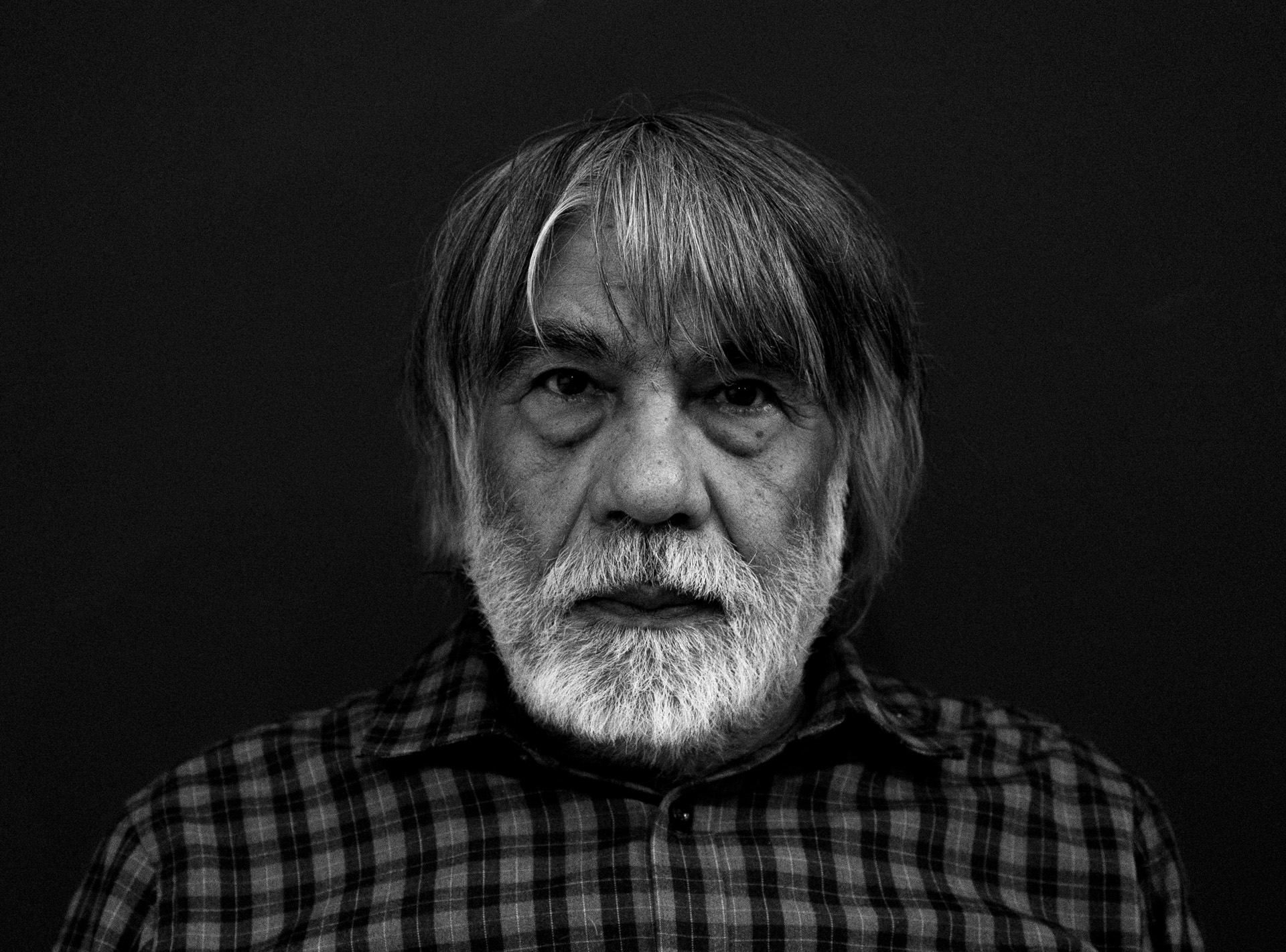

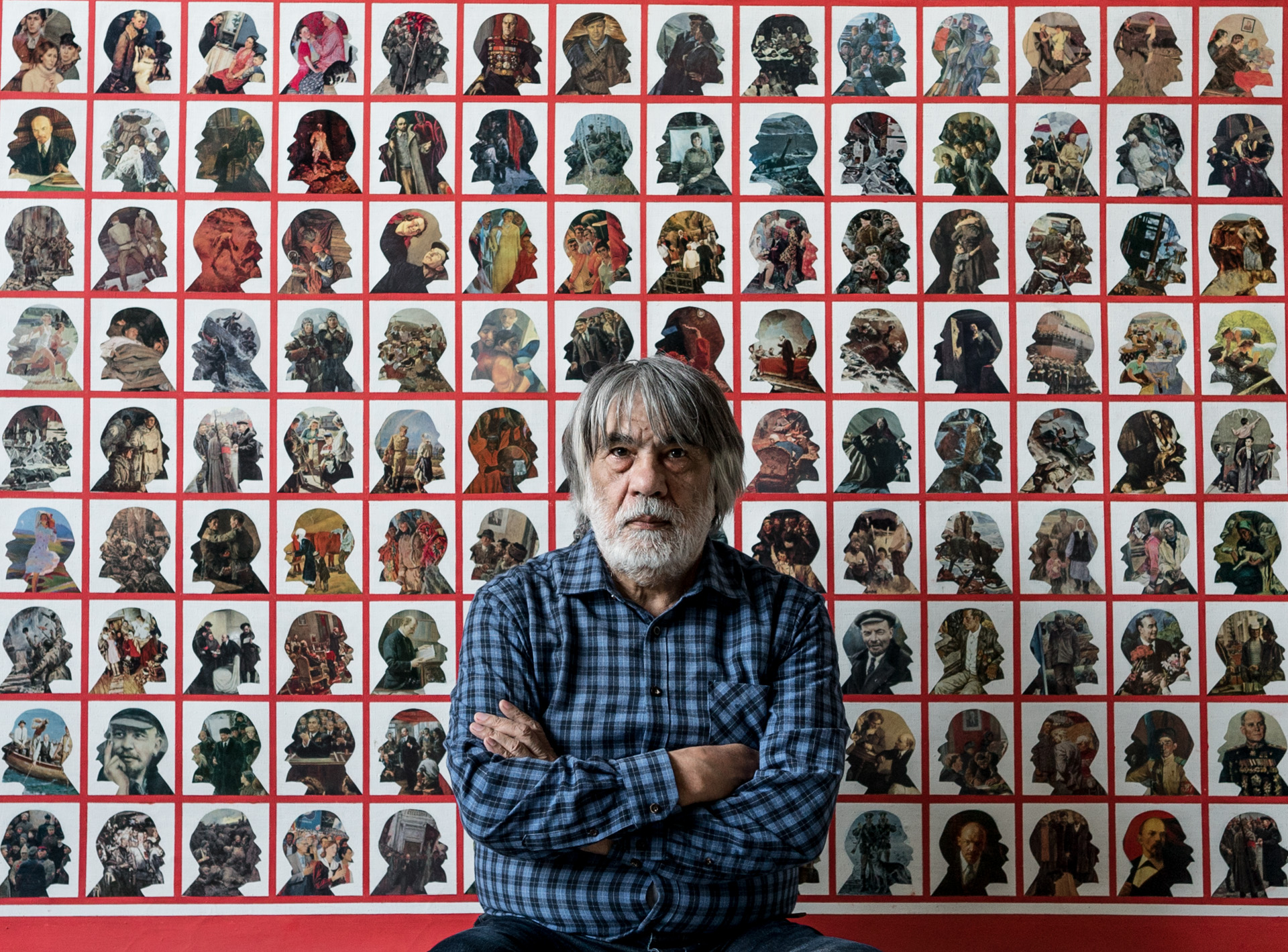

Vyacheslavv Akhunov is an outstanding artist, the first contemporary nonconformist artist in Uzbekistan, writer, and philosopher. He is a key figure in the contemporary art of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia. He created hundreds of works in various mediums and techniques: painting, video, collage, installation, essay, performance, new media. In early 2010s Uzbekistan authorities banned Vyacheslav Akhunov from leaving the country and would not issue an “exit visa” to him for many years.

Despite the pressure, the artist continued to work and experiment with different forms of art.

Vyacheslav Akhunov is not only one of the brightest and exuberant conceptual artists in Central Asia; he has also become one of the main symbols of freethinking and artistic integrity in his country and far beyond it.

CHILDHOOD

I was born in 1948 in Osh, at the maternity hospital on Stalin street. I went to kindergarten and school in Osh.

When asked for a portfolio, I usually call myself a Kyrgyz-Uzbek artist because I lived in Kyrgyzstan for almost 30 years, and I was shaped as an artist there. While Moscow was the place where I was shaped as a contemporary artist, it was Kyrgyzstan where I had been shaped as an artist in general.

When I was born, my father served as an artist in the army, at a border unit in Osh. He was given a small room in an old madrasah that functioned as a museum. We lived there for 3 years. It was a typical regional historical museum. I remember myself as a three-year-old kid running around among the exhibits: ancient jars, skeletons and weapons.

Later we were given a room in an 18-century mud house. There were no windows, and the door led straight to the street bustling with waggons, people, and donkeys at the foot of Suleiman mountain.

Electric lighting was available only in the European part of Osh, and there was no power in the old city: the indigenous part. When we sat for dinner in our room lit by a kerosine lamp, scorpions would come out and crawl up the walls. My father would just sweep them into a can and take it outside. I was too little to realize how dangerous that was, but now I understand why all the beds were always kept away from walls.

The city was growing, new people were coming, and then the art studio was opened at the city service center. That studio was for making signboards, propaganda posters and communist leaders’ portraits. So my father had been given a room in a barrack, which he then enlarged by adding another small room and a terrace to it. It was a true 1950s barrack, inhabited by people of different ethnic backgrounds, each had their own closet — just stunning!

Our home used to be a terminal base for the expeditions. Archaeologists always stayed at our place. In summer, my father would work in archaeological teams. In 1956, together with Yuri Baruzdin, head of the expedition, they went to a place called Karabulak in Batken region. Eight years old, I latched onto dad. The famous female mummies that are now burried back into the ground at the request of local sorceresses were discovered during that expedition trip. There was not just one burial site as it’s now claimed in the media but a whole cemetery. I can still recall how the first grave was uncovered. It was all happening before my very eyes.

During the expedition to Alay valley Yuri Baruzdin’s son Sasha and I would play together. To help the lady cook, we collected pressed dung that she then used as fuel to cook meals for the expedition team. In 1963, the expedition departed for the last time. Somewhere in Kazakh steppes, on the way to Frunze, their car overturned, the gas spilled and burst into flames. Several people managed to jump out and survived, but the driver, Baruzdin, his son, and two History students died. It was a tragedy, and so the South-Kyrgyz archeological expedition died.

WAR’S AFTERMATH

The impact of the war in Osh was very noticeable. There was a Russian cemetery behind our barracks. Almost everyday you could hear funeral processions, sometimes even two: one followed by another. Slowly, across the town, with music… Everyone would come out of their houses and give a send-off to the deceased, most of whom were the veterans who died from injuries.

There were many veterans in the city. And there were the exiled who had returned from the labor camps but were not allowed into Moscow or anywhere else. The exiled were of two kinds: criminals and political prisoners. The criminals would work in laborious production. Sometimes I went to the districts where they lived and listened to them sing camp songs; I even knew some of them by heart. As for the politicals, usually they were intellectuals: smart people with books. They wouldn’t interact with the criminals in any way and preferred not to live in the same neighborhood with them. They usually worked as supply managers’ assistants, park workers, receptionists, or joined the geological expeditions for the summer: just to be outside the city.

And there were disabled people: legless, moving around the city and the bazaars in their hand-made wheel chairs and collecting alms.

Image by Malika Autalipova

OSH

Post-war Osh was divided into the new, Russian, and the old city. The old city was all about mahallas, guvalyak fences, adobe homes covered with grass and mud. In spring poppies would blossom right on the roofs… Ah, what a beautiful sight! The flowers grew because the mud used to coat the roofs was brought from the fields and contained seeds. Spacious yards with fruit trees, houses with iwans, wooden couches and tandyrs.

And of course, there was a bazaar. It was a huge bazaar along the river, and everything there was very thoughtfully arranged: blacksmiths would sit at one place, Uyghurs would cook lagman at another one; there was a special place where rice was sold and different ones for potatoes, spices or hay for the cattle. On Sundays, Kyrgyzs would bring rugs and sheepskin coats down from the mountains and barter them for other goods. Fruit and vegetables were brought from Andijan, Kuva and Hadji-Abad. Numerous chaikhanas were scattered along the river. The Navoi park in front of the bazaar had a poolhall where people could read filed newspapers or play chess. And there were more chaikhanas. People would buy groceries and head there to cook plov and enjoy it, sitting right on the river bank. But it was the indigenous part; its borders were clearly defined, and Russians didn’t live there.

The Russian town, built around the 19-century fortress, was just across the street. Used as a military unit, the fortress was surrounded by houses where commanders lived with their families. The command unit, the border unit and the old post office building were all nearby. And of course, there was the Officers’ House with film nights, weekend dancing and refreshments for the officers.

The town had a chain of stores: records, groceries, recreational supplies, sport equipment. Recruiting station, the Communist Party regional committee, culture park, Komsomol lake, Pamir restaurant, cinema. There was a bazaar next to the military unit, and from as early as tsarist era it was dubbed Drunk bazaar because cheap joints there offered vodka and wine on tap. And many cities had their drunk bazaars.

That part of the city had its own schools where there was no education in the national language: only in Russian. I studied at the Lomonosov Russian school. We had Germans, Koreans, Jews, Kyrgyzs, and Uzbeks in our class. But we never even knew what nationality was; we simply didn’t care.

I remember that nearby my father’s studio there was a building with a basement where Chingiz Aitmatov lived for some time. I used to go after the water to the river behind that building.

The division was very clear. You could walk just 500 meters and find yourself in a completely different culture that lived its own life. And for us, the kids who had grown up in the Russian part of the city, being in the indigenous part felt weird. It was a different and mysterious world, a world we couldn’t entirely comprehend. It was the Oriental world.

Then you go just 10 kilometers away from the city, to the mountains, and you’re surrounded by another culture: with yurts, kumys, and horses. And the life is absolutely different out there: autumn marks the beginning of the equestrian plays season.

And on the other side, only a kilometer away from Osh, beyond the Uzbek border, everything is different.

There is a sacred Suleiman mountain in Osh. Before the revolution, there used to be many mosques and madrasahs that later functioned as museums. When the anti-religion campaign started in 1962, they were destroyed.

ARMY

At the age of 14, I was admitted to the art school in Frunze, so I moved to the city. There were no dormitories back then, so I had to knock about from place to place. To me, a boy who was used to living with parents, with an artist father, all that was difficult; so on the second year of studies, unable to bear it any longer, I quit and escaped back home: to Osh. I finished the school and decided to enter a university but failed. So I worked at some construction site and was then taken to the army.

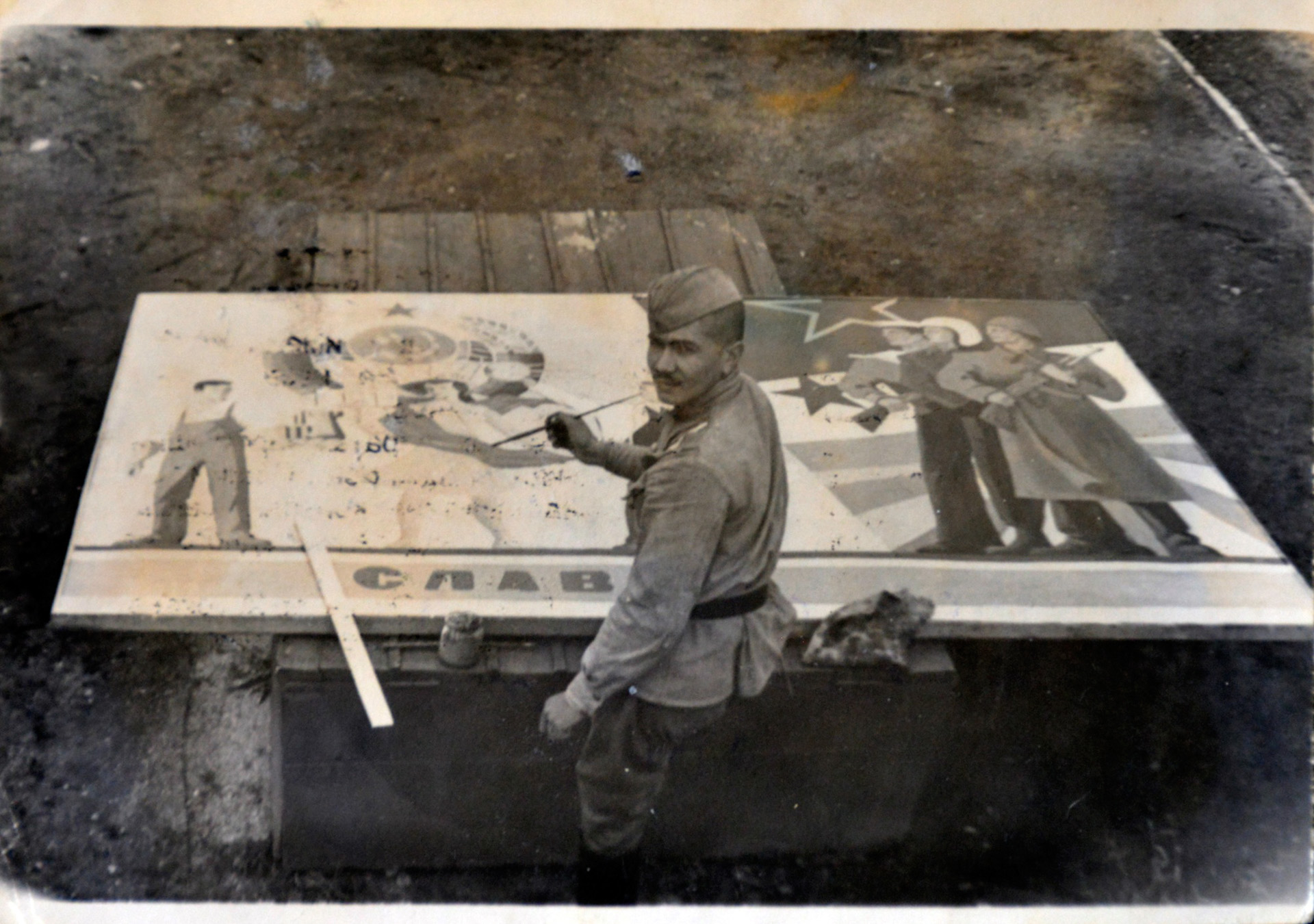

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

I did my service in Zagorsk town in Moscow region. It lasted over two years but passed so quickly. As an artist, I was responsible for designing the Lenin’s rooms. So I painted, glued and made collages. That experience was priceless.

Actually, I got my first lessons in collage making as a kid: from my mother. She was a teacher in kindergarten, where she was told, “If you’re an artist’s wife, you know how to draw. So you’ll be making the bulletin-board posters”. But since my mom didn’t know how to draw, she would scissor out pictures from magazines and collage them. And I would sit by her side, watch, and help her. So my first experience in the collage technique came not from my artist father but from my mother.

Later, when I was 13 or 14 years old, dad would bring large canvases home and make communist leaders’ portraits. Often, he didn’t feel like painting some of the parts, so he would thin down the paint for me, and I would just dye the black suits and backgrounds. That’s how my father accustomed me to portraying the chiefs. Who knows, maybe it all has been accumulating on some unconscious levels since back then.

ART

When I was in the army, I once went awol to finally visit the Tretyakov gallery and see all the famous paintings by Surikov, Shishkin, Repin. So I arrived in Moscow, came to Larushinsky lane to find out the museum was closed. “Don’t be upset, there is another one that is open: the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts,” I was told. Following the doorman’s advice, I went to the Pushkin. And there I got acquainted with Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, van Gogh, Picasso, Derain, Vlaminck, Marquet, André Fougeron’s solo exhibition!

My father would laugh and say, “You saw all those obscurants and got infected; now you’re an obscurant yourself…”. It was the love at first sight. The moment I saw it, I was enchanted… It felt so fresh, striking, mind-blowing…

Suddenly, I realized where all those Osmerkinists and the Jack of Diamonds that I had seen in the Frunze museum originated from. They all had references. I fell in love with that other art.

Coming back from the army, I brought a bass guitar and a solo guitar with me, started a rock band, and would right music and lyrics. It was the era of admiration for The Beatles.

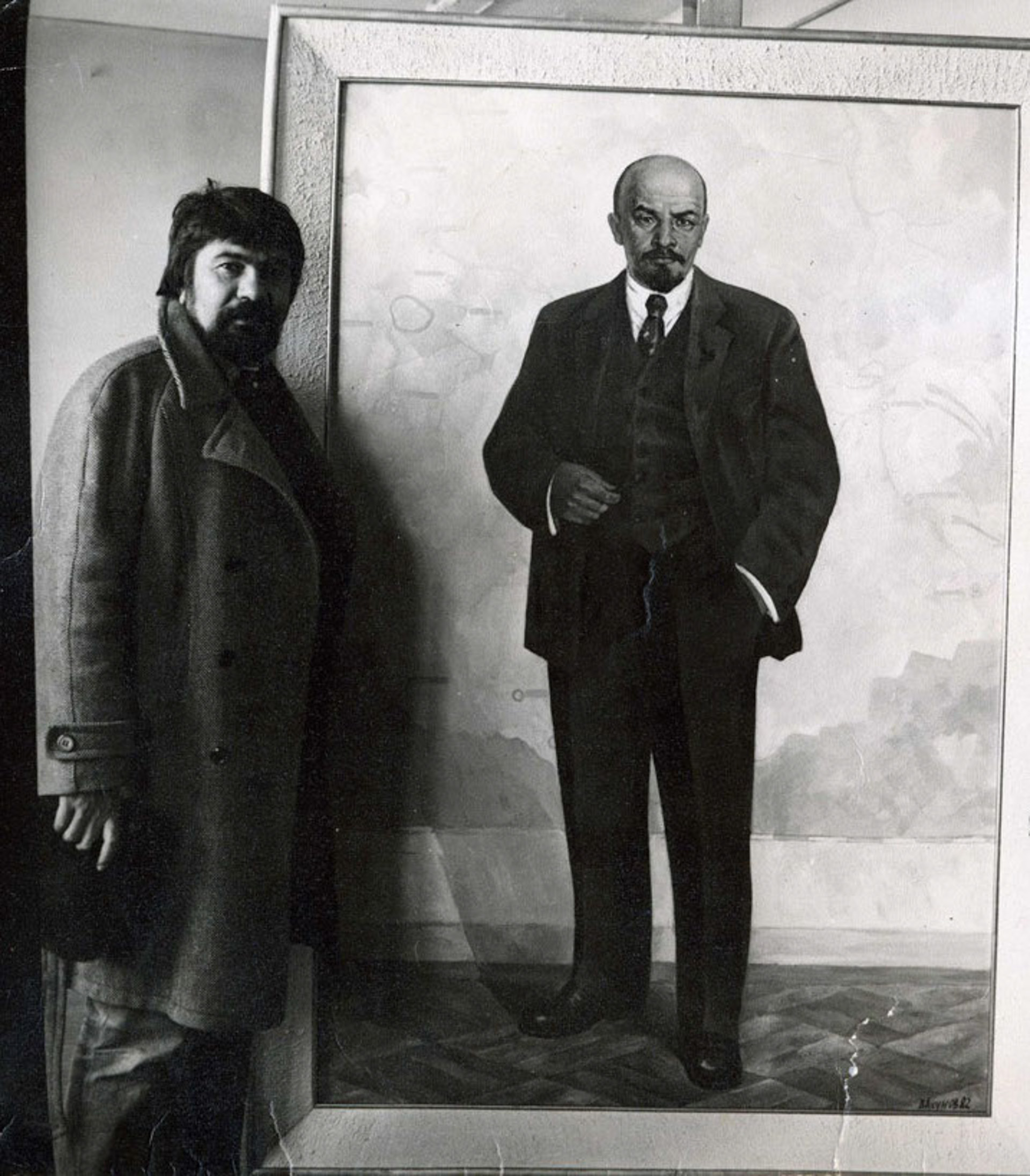

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

In the summertime, we played at the city park dance floor, and in the wintertime we’d perform at a restaurant. My dad once came to the restaurant and said, “I am going on a road trip on motorcycles around Central Asia with my friends. We’ll be traveling and painting; would you like to join?” I handed my guitar to the guys and went with my father.

We rode through Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, part of Kyrgyzstan. We made a detour to Bukhara and then back to Osh, through Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Motorcycles only. Thanks to that adventure, I got back to drawing.

In 1971 there was an exhibition “Artist, Land and People” in the old Frunze museum, and a work I had made outside Samarkand was presented there. They wrote in the newspaper that the republic’s youngest artist and the oldest one are exhibiting their works at the same venue. They meant Semyon Chuikov: our works were hung next to each other.

Lidiya Ilyina and Gapar Aitiyev said to my father, “Urumbai, your son should finish his studies. Get him back to school.” Now that Kyrgyzstan’s foremost artist had said that, I enrolled back to the art school as a third-year program.

A year later, I finished the school and was sent to Tallin to study at the art institute there. Together with other fellows who also had reference letters from the republic, I got on a north-westbound train. As we reached Moscow, I latched onto the guys who came to enter the Surikov Institute: just to see what the place was like.

I liked it so much that eventually I changed my mind about Tallin and decided to stay. I submitted the documents and got enrolled in the institute’s painting department. We lived in GITIS’ dormitory because our institute leased a part of their second floor.

In that dorm I met Ula, a girl from Finland who was working on her dissertation on education: a comparative analysis of the capitalist and socialist systems. We became friends and fell in love with each other. Back then, she would go to the non-conformist artists’ workshops. With her, I got to visit Kabakov, Sooster, Yankilevsky in their studios.

Ula spoke Russian with a strong accent. In my Levi’s outfit and aviator sunglasses I didn’t look like a Soviet man either. The artists would take me for a Latino or a Spanish, and gladly showed their works. There, in those workshops, I realized that there was a completely different kind of art.

I remember that famous exhibition at VDNKh’s Honeycraft pavillion in 1975: it was the first official non-conformist artists’ show. Ula and I visited it, too. It was amazing.

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

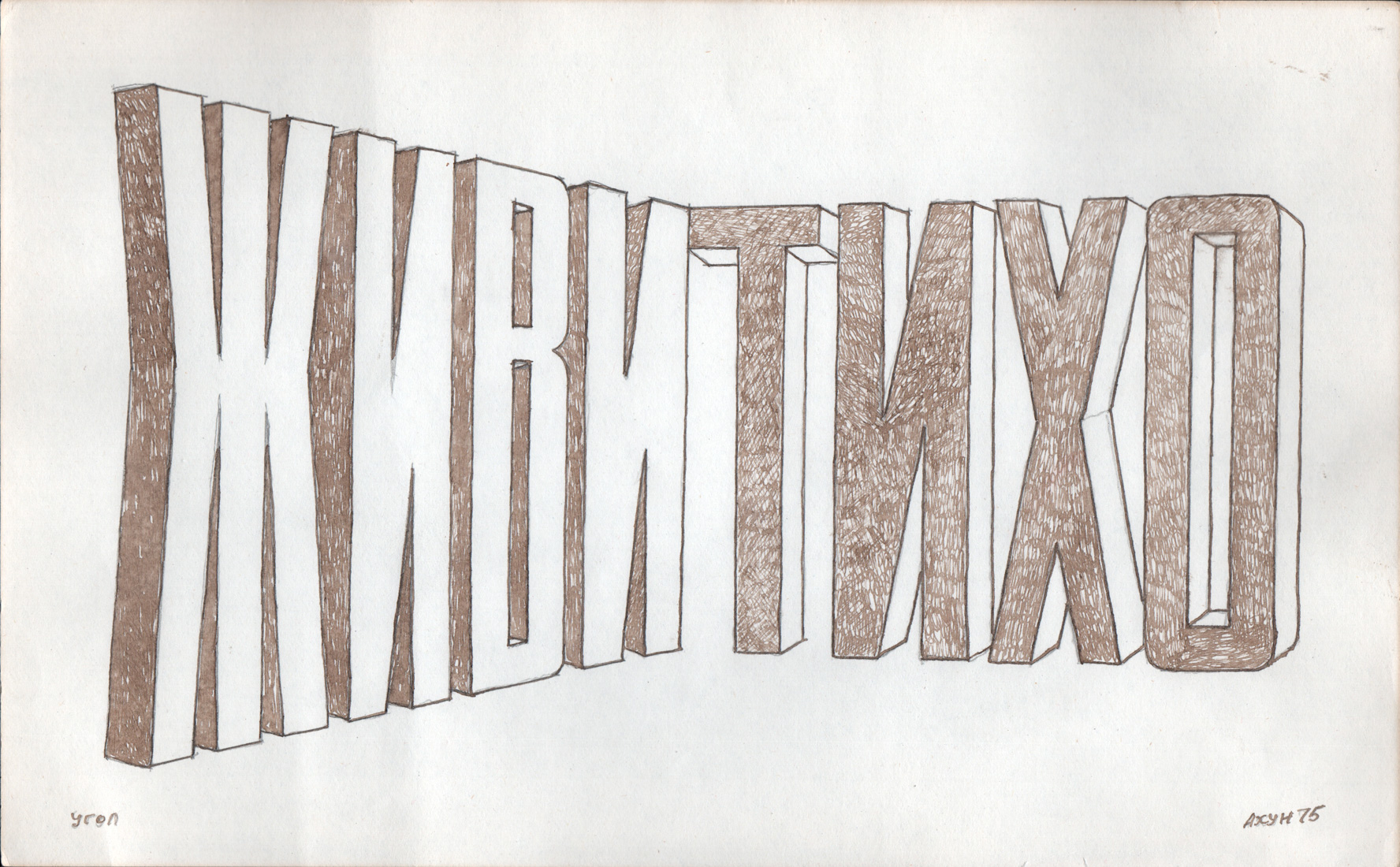

THE SOCIOLITHIC ERA

My first artwork happened by chance, when I didn’t even think of myself as a conceptual or contemporary artist at all. It was winter; I was walking along Taganka to the institute. At that time old wooden dwellings in central Moscow were demolished and people were moved out to remote districts. KGB officers and political bosses — and sometimes distinguished workers and foremen — got apartments in the new, high-end buildings that were replacing the old ones.

On that day, one of those old dwellings was being demolished; the site was full of lumber and stuff left by former inhabitants. Suddenly, I saw a red album and came closer to see what was inside. I thought: what if there are drawings, or something valuable, or antique, or maybe there are empty sheets that I can use for drawing? I picked it up. It appeared to be a tailoress’ album with sewing patterns for dresses, skirts, panties and bras. In sixties, mass production of clothing hadn’t picked up after the war yet. So I put that album in my bag and left.

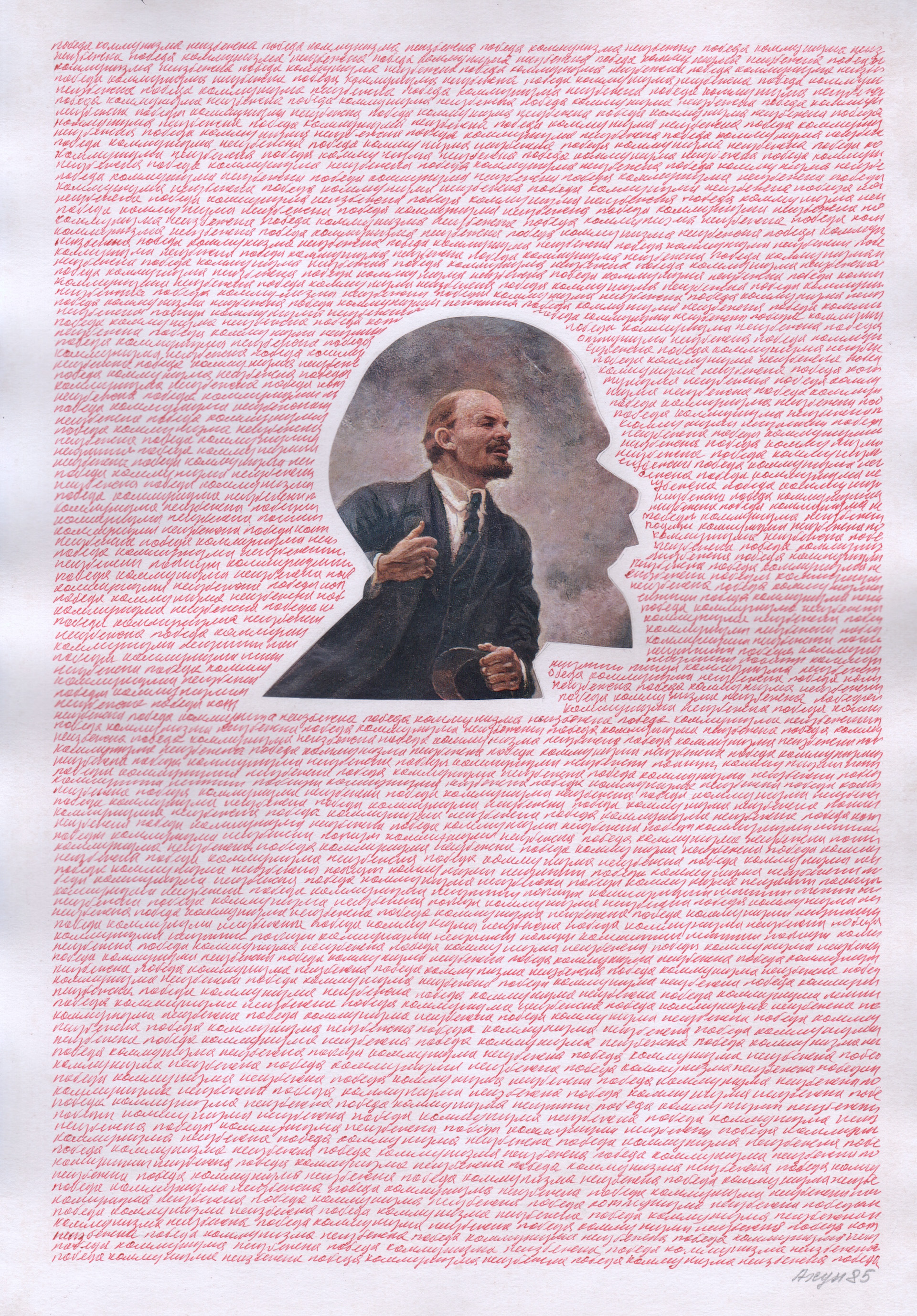

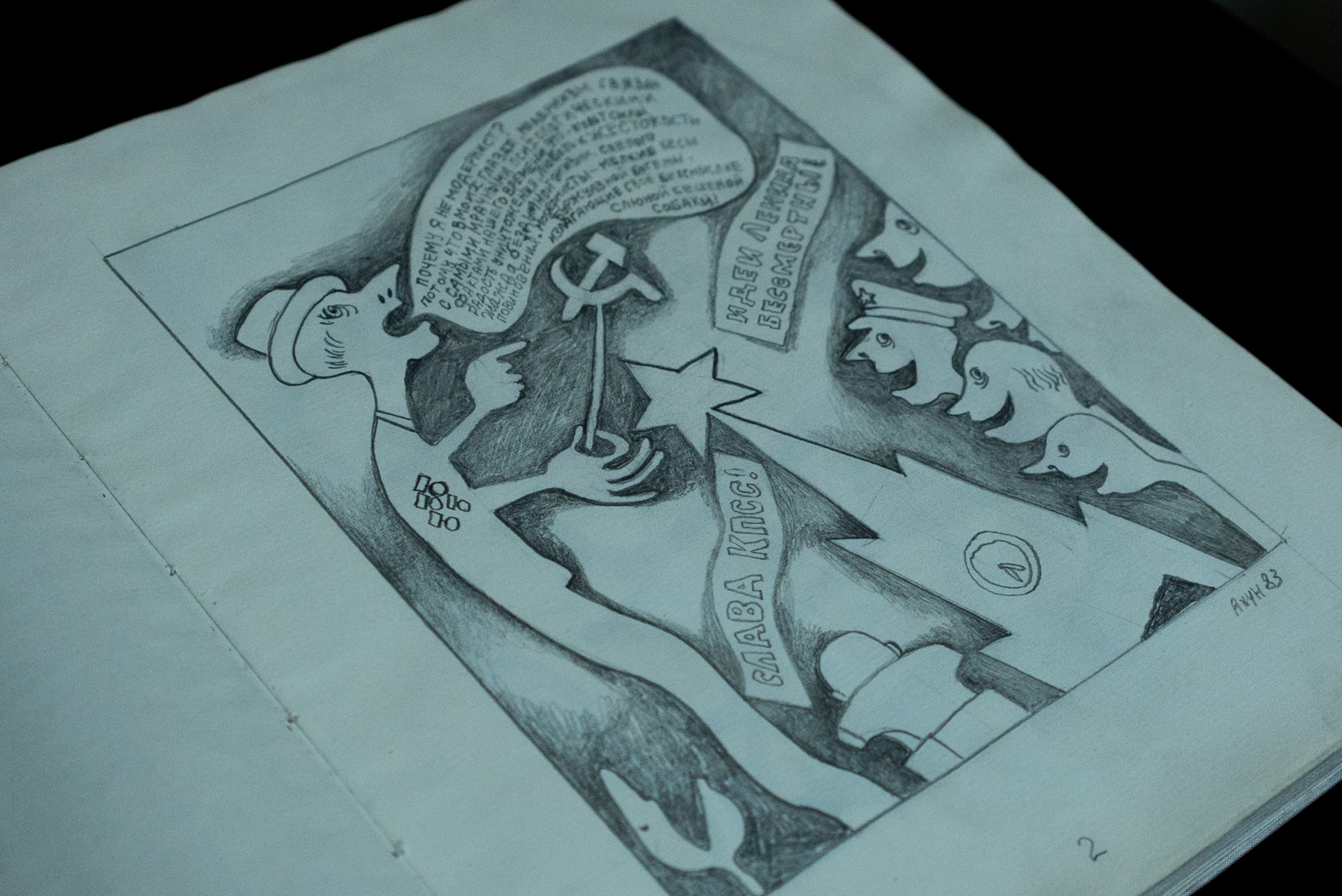

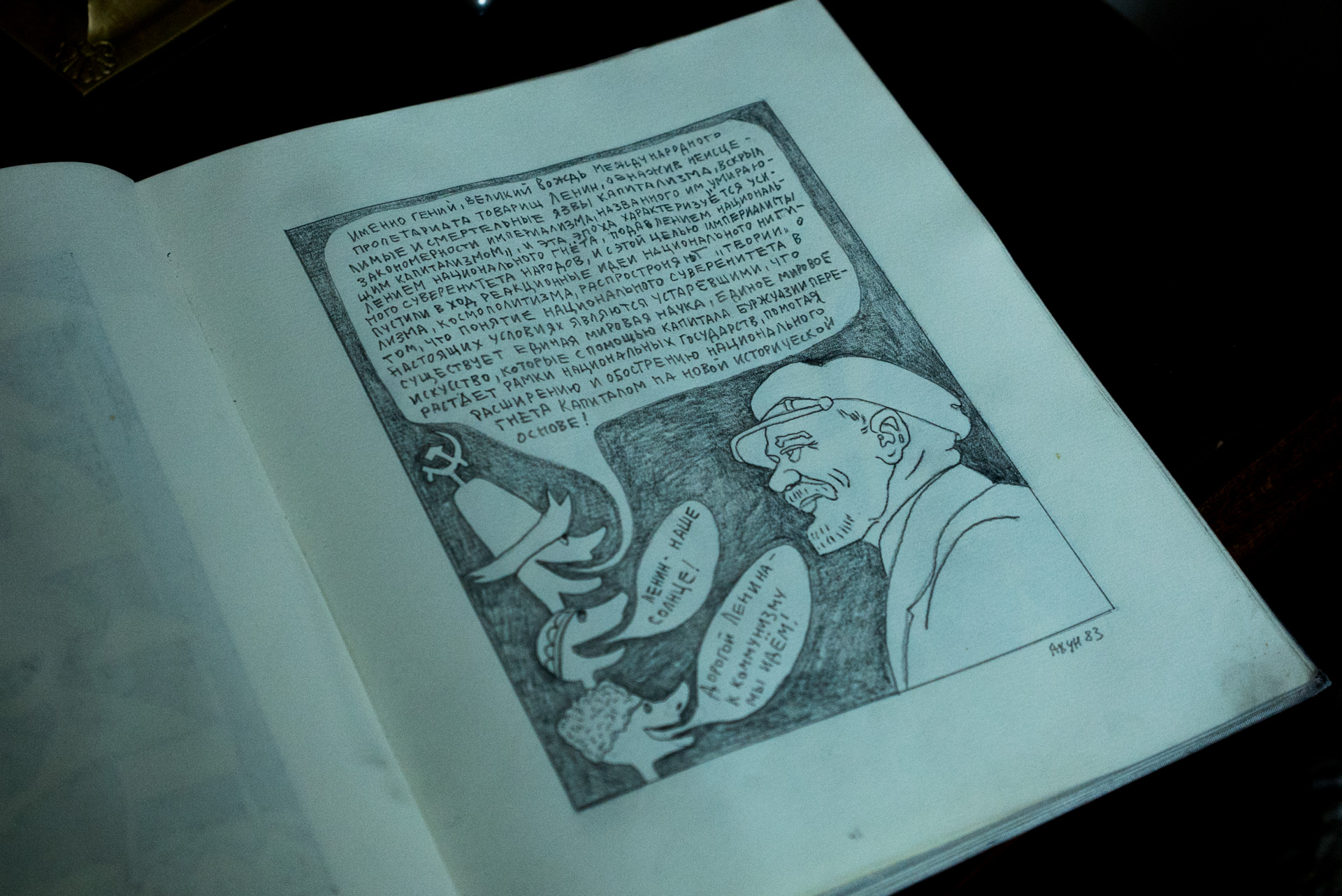

At the institute we had afternoon lectures in Marxism-Leninism, scientific communism, arts, dialectic materialism, history of the Communist Party… And students were supposed to make notes. Out of laziness, I started to write those lectures down right on the sewing patters. Then a thought struck me: if you make a dress out of such patterns, you could actually wear the ideology. I filled these patterns with lectures in Marxism-Leninism; and that was my first individual work. Now it’s in a museum; it was bought from the Moscow biennial. So my very first project later transformed into a huge series: the Mantras.

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

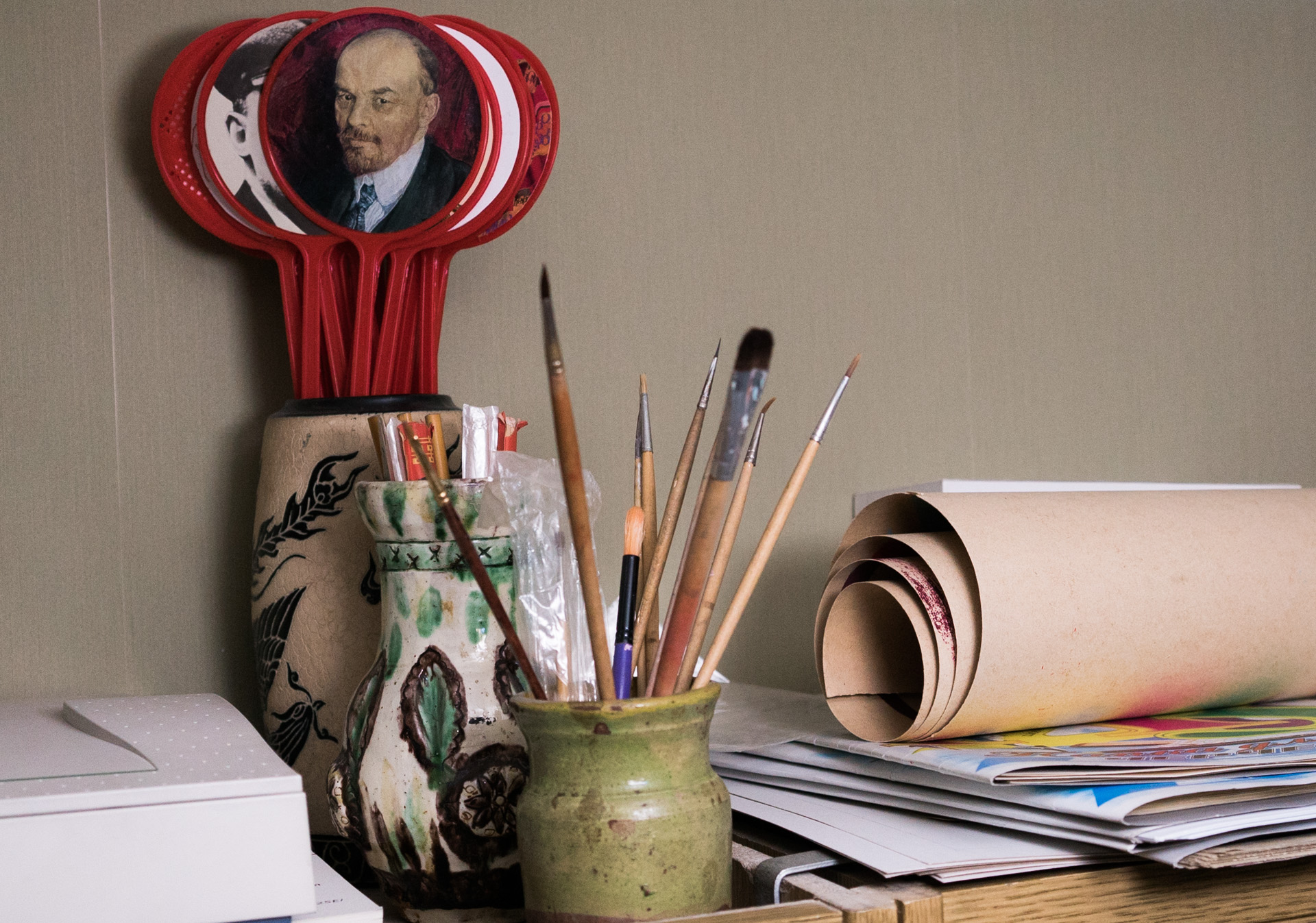

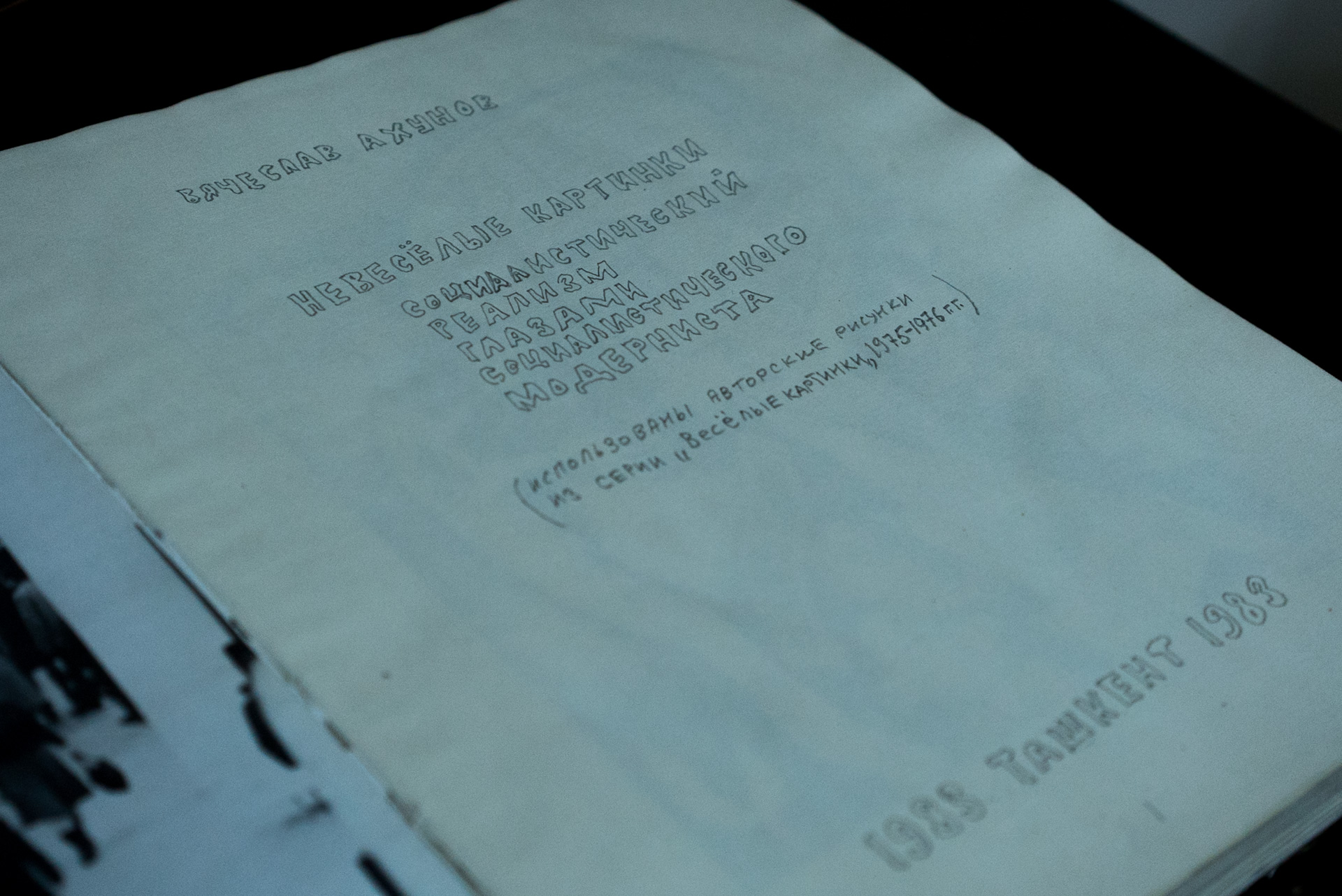

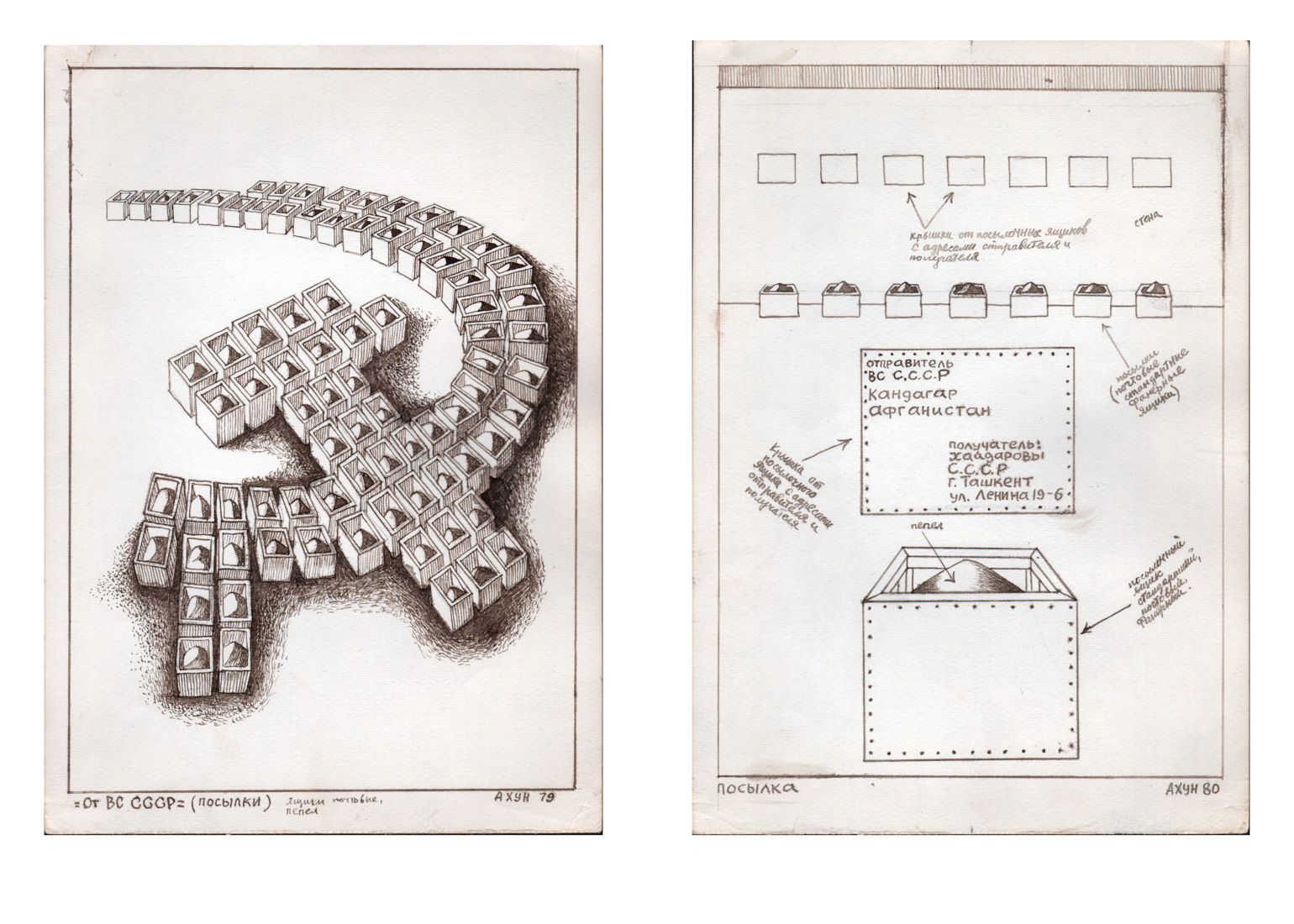

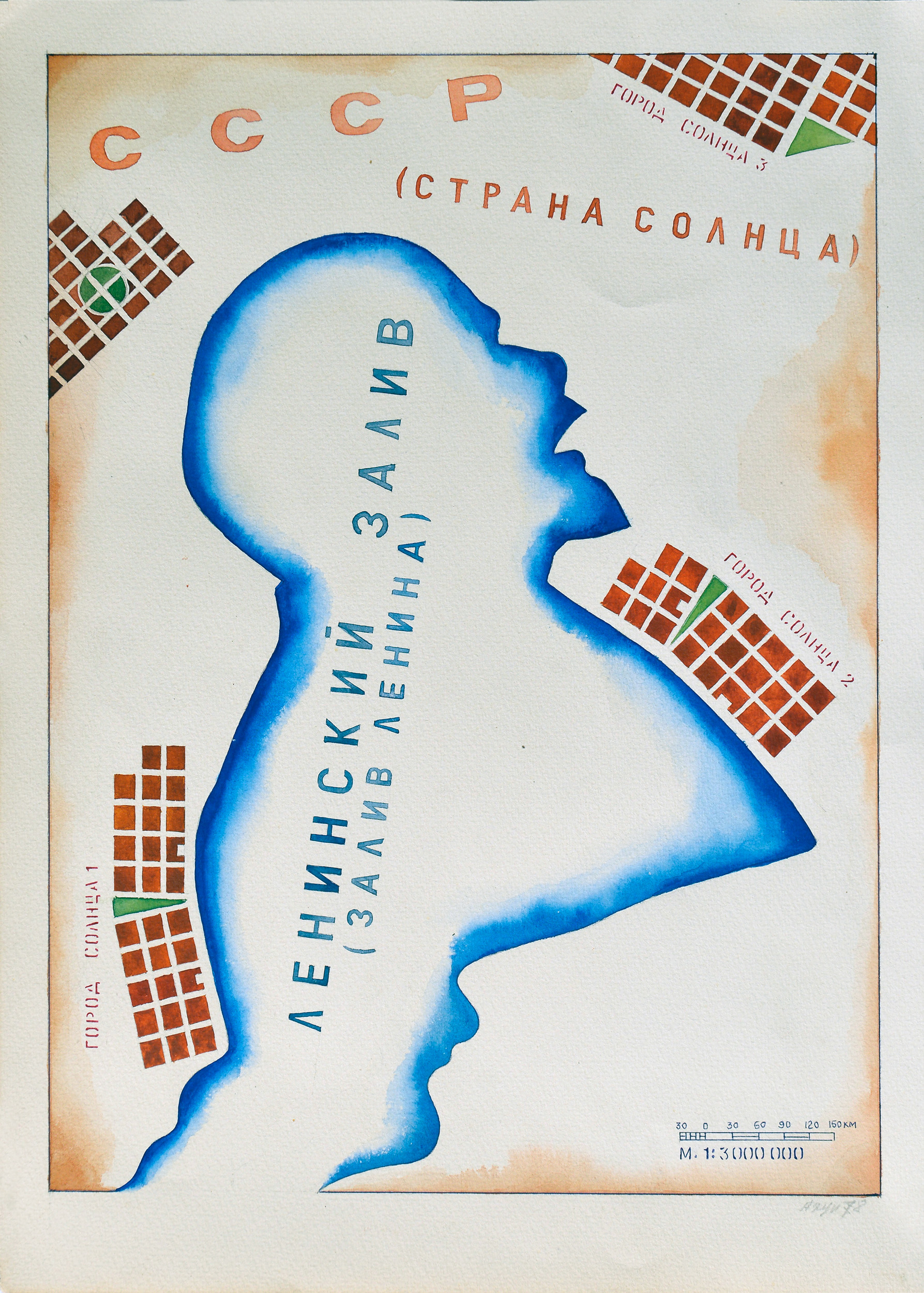

And there was another series. As a kid, I used to travel with my father a lot. Our family lived in a museum. All that experience had been living somewhere inside me for years and suddenly manifested itself in my artwork. I imagined that in thousands of years from then archaeologists would discover an unknown culture which they would name a Sociolithic era. There were the Neolithic and Paleolithic ages, and this one would be the Sociolithic one. They would unearth ceramic fragments with “Glory of the Communist Party” written on them, or some vessels with Lenin’s portraits. I started to draw all that, forming an archaeological collection. I would sketch the “unearthed” ossuaries. Ossuary is a special chest or box for human bones. I drew ossuaries in the shape of the Kremlin, Lenin’s Mausoleum, Kremlin towers… Of course, in Osh no one comprehended these works.

When I came to Moscow city committee with my “fly-flaps” with the communist leaders portrayed on them, I was booted out and called a rabble-rouser who wants the place to be shut down and so on. And even now, when I displayed the fly-flaps at my solo exhibition, communists came, all bursting with indignation and complaining. Even fellow artists would tell me, “How could you?” And I realized: back then I’d be put in a nuthouse, for sure.

I remember my father say, disappointed, “I though you’d be an artist, but you’ve become a bigot.” That was when I noticed that some of my works started to disappear. My father feared I’d get arrested by KGB and so he was secretly tearing up my works.

Image by Malika Autalipova

MUSIC & PROTEST

In 1979, I graduated and came back, to follow my own way. At first, I was torn between Fergana and Osh, but then I moved my parents to Tashkent and settled down here for good.

There was not a single underground artist around: that culture simply did not exist here. And still, local artists don’t even have an impulse towards making something in a different, uncommon way.

Ask anyone why, and they would talk about money, alleging that artists have to feed their families. But it’s now how it works. Whether you want it or nor, the need to do things differently is a part of you. You’re born this way. You’re born with a protest inside you.

I remember when in 1956 dad bought a Daugava radio, I was tuning the dial and found a heavenly beautiful music. I clung to that radio. It was my music. Oh what a feeling it was!

Something stirred me up: I felt so vividly that it was my music and I’d heard it before. That was a British station broadcasting from the island of Ceylon. It was playing jazz. I marked the frequency and whenever my parents weren’t around, I’d tune in and listen, listen… I was 8 or 9 years old, and I knew that jazz was my music.

In later 1950s, the “stilyagi” came around, wearing tight trousers and bright shirts; older guys in the neighborhood would share the “bones” and boogie-woogie records.

Our neighbors, Soldatkin brothers, would redesign radio receivers to capture the shortest waves, so that we could listen to broadcasts from the West.

That was an eye-opening experience for me because it made me realize that a completely different kind of music existed; I realized that our, Soviet, music was all made of march tunes: bam, bam, bam. But this music was different, not military at all. It was simply beautiful. You can’t march to it. And the protest — against regimentation, marching and all that — was rooted deeply in my mind.

Another bemusement happened when I first heard The Beatles. But that was much later, long after jazz.

And the third bemusing experience was in 1970. I came back from the army, and my sister gave me Deep Purple’s record. Then I discovered Led Zeppelin and the others.

All these experiences shaped my personality. Not as an artist, but as a person in general. However, later, the very same things played a part in the making of me as an artist, too: the love of all things Western, love of modernism. And that was when I made my first attempts in modernism.

Image by Malika Autalipova

Image by Malika Autalipova

Image by Malika Autalipova

Certainly, literature shaped me as well. In 1970s the Foreign Literature magazine published a lot of novels. First of all, Latin American prose, magical realism. García Márquez, Cortázar, Borges. Second, modern Japanese literature: Kōbō Abe. And third, modern French novels. Nathalie Sarraute… In poetry, undoubtedly, it was the Italians.

Movies played a major part, too. And again: Italian, of course. There were very few American films available at that time.

Bit by bit, modernist art and forbidden literature were penetrating, through magazines and underground press. It was the underground press where I first read Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, and where I got acquainted with Kandinsky; his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art is breath-taking. Some of Malevich’s works came out in the underground press, too.

I was lucky to live next door to Dudintsev, a great writer and author of the novel Not by Bread Alone. We would talk a lot. He once said, “They want to send you to work at the Baikal-Amur Mainline construction. Why? Why wouldn’t they send you to Italy?” These conversations helped open my eyes to many things.

Those were the things that shaped me…

In 1989, when I visited America for the first time, I travelled about forty cities. I came back home devastated because I realized that everything had been done already. Whatever you want to do, whatever idea comes to your mind, it is all done long before. We just didn’t have information; we lived behind the iron curtain. We were reinventing the wheel.

It was the time to relearn and devour literature. In my student years Ula had brought literature from Helsinki for me: books on dadaism, surrealism, and minimalism, Camilla Gray’s The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863—1922 — my first textbooks. She would bring them along with The Beatles vinyls. That’s how I started to develop as a protest artist.

CONFINEMENT

In Soviet times, I used to in some way ironize the official art and the method of socialist realism, and actually worked in counterculture. But now I am exploring the Soviet subject. It was a major historical phenomenon: a futuristic experiment, an aspiration for the future, a utopia. However, that utopian art was one of the significant achievements in world art. You can't deny it and say it was rubbish.

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

However, I work with the present as well. For instance, I made a 25-meter long installation in Berlin — Political Clowns. The stars on my 42-meter long Walk of Fame in Kiev bore the names of anti-heroes who had ever started wars. Medvedev got a star for Georgia, and so did Putin. Stalin, Lenin, Hitler — all of them. It was 2 years before the war in Ukraine started, but I gave Putin his star because I knew who he really was. A presentiment.

It was 2012, and by that time I had already been banned from leaving the country.

When the Maidan started, and the first victim died on the barricade, Oleg Kharchenko and I installed a temporary monument to fallen heroes in Kyiv. It was made of styrofoam letters glued together into “Glory to the heroes of Maidan”. People lit candles and placed them on the monument.

Since I could not go to Kyiv, I had to manage the process from here.

Last year, Oleg and I made another project together — Language Correlations, that paralleled Ukrainian language with the Turkic ones. We did it for a contemporary art exhibition in Tashkent. These works would have never made it to the exhibition hall if they had my name on them, so we decided to put only Oleg’s last name.

Recently, there was an exhibition dedicated to the 25th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Ukraine and Uzbekistan, and this time my name was included in the captions. At the opening event a man approached the ambassador and told him,“Sir, do you know that this is not Akhunov’s work? It was made by other artists, and he has nothing to do with it.” Caught off-guard by the man’s status, Mister Savchenko almost believed him.

I “earned” this kind of attitude towards me in 2000, when I started to expose socially themed works.

At the President’s Council they kept asking Kuziyev, “Those artists are overplaying their hand. Why don’t you watch out for them?” But he couldn’t tell them I wasn’t a member of the academy, and that I was actually independent. So what they did is they took a work by Said Atabekov, Besik — the one with a Kalashnikov on a cradle, and passed it off as my work. And so they lashed out up there, “Ban him! Shut him up! Put him in jail!” And that was it.

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

From Vyacheslav Akhunov's personal archives

Another moment, a very important one: a group of art curators came to Tashkent, and when they saw my archive, they were so shocked that they decided to exhibit 80 of my works at the Istanbul Biennial. So in just one day I became a star. People who once had been forced to emigrate from Uzbekistan — politicians, speakers — came to see the show. 80 artworks! Happy for their fellow countryman and for Uzbekistan, they made a celebration dinner.

Soon after I came back, a visa in my passport expired, and they refused to issue a new one. They knew it was too late to put me in jail because public awareness was growing, but locking me in like that was just fine. So I got stuck for six years.

ARTIST

In 1950s, they used to say Middle Asia instead of Central Asia, and the previous way is actually more familiar to my ear. I think that the whole process of adjusting the boundaries and dividing into republics was artificial and completely absurd. Nations and their lands were ruthlessly cut in pieces. I always imagined this region as a single whole. In Soviet times, on the way from Fergana to Tashkent you’d cross Kyrgyz, Tajik and Uzbek borders five times.

I always say that all artists are different. My father enjoyed painting landscapes from nature. Someone else sees himself as a craftsman: he paints to earn money. The other one can’t live without public activity. But there’s one kind of public activity: becoming a boss at some union or guild. And there’s another one: it’s when a person sees things and addresses important social problems.

There’s this tale that comes to my mind whenever I think of the artist’s role. A worker at the Notre-Dame de Paris construction site is asked, “Sir, what are you doing here?” “I just can’t sit idly, I need to work. So here I am, working,” he responds. Then the asker approaches another worker with the same question, and the man replies, “I ran into debt, so now I need to earn some money to pay it back.” And the third man says, “Sir, can’t you see? I am building Notre-Dame!”

And that “I am building Notre-Dame” is the key: he considers himself as the builder, not just a worker. He is building a temple. And artists are building a temple, too. They are constructing it from the bricks of narratives and projects.

Think, for instance, of the Itinerants. They tackled really acute issues in the society. Do you know how much debate the Burlaki raise in Russian press? You’ll be surprised if you just look at how much mud was thrown at him. “Who needs that?”, “Poor Russia is dead in the water, and he dares to show it that way!”

And now, all of a sudden, people claim we don’t need that kind of art, the social art. What do you mean we don’t need it?

We all feel ourselves differently. Some people feel responsibility for raising awareness of the problems: without it society would be faceless, conformist, terrible… As for the others, they prefer sitting idly and keep saying that just making things pretty in enough.

Image by Malika Autalipova

Image by Malika Autalipova

Contemporary art consumes more money than the traditional art. Traditional artist needs a canvas and paints for work, that’s it. But contemporary art is different: it can be video, installation, or some big multimedia projects. A single project could cost 20–30 thousand dollars, or half a million. Therefore, contemporary art can exist only in advanced, rich countries that have money for culture. As for countries like ours, there can’t be contemporary art, but there can be contemporary artists. Individuals. And if only they got support not just from abroad but at home too, they could implement great projects just as well.

NOT AN ARTIST

In Soviet times, people were forced to worship a new God, the communist God; so they had to conform. For decades, several generations were being compressed like a spring, and anything religious was knocked out of them. It was the era of a complete atheism: on every level. And then, the Soviet Union collapses. Total freedom: do, think, and feel whatever you want. Turns out, the old beliefs didn’t go anywhere. Look at how quickly castes and tribalism reverted. People immediately recollected who came from where and who belonged to which tribe. “White bone”, “don’t marry her”, “we’re not going to let our daughter marry him” and so on. Instantly: as if it was yesterday. In fact, it never really left; it was just hidden, repressed. The communists were compressing the spring, and it snapped back really hard. But the nature abhors a vacuum. It has to be filled, always. And what do you fill the post-totalitarian vacuum with? With another kind of totalitarianism, a religious one. All of a sudden, the Earth is flat again.

Nowadays, the locals — the elite — inherited the colonist’s role. They became their own nation’s colonizers. And they adopt the very same methods that the colonists of a different nationality would use against them in the past. Naturally, this “inverse decolonization” raised a new wave of religious obscurants and downright outcasts who are now running the show.

But really, the society itself has to become liberal and democratic enough, to translate its values and freedoms to the authorities. Why is freedom of speech important? It helps expose corrupt officials. Why is democracy important? It creates institutions that oversee each other. Why is the multi-party system a part of democracy? It creates a counterbalance. It is important to oversee the judges, prosecutors, and generally, all the branches of power. But none of these exists, and so everything is just rolling back.

So I am going to repeat it again and again: we need contemporary art. Not all those pretty still-life and landscape paintings. An artist’s weapon is his literature, his paints, his art. By these means an artist can manifest and defend his views and democratic principles.

But no one here even considers the art as a way to do so.

A few years ago there was a biennial here in Tashkent; it was called “Territory of Art”. And, as usual, not a single work at that exhibition reflected a socially relevant theme. So I made a performance. I made myself a badge that said “Please do not bother me! I am not an artist.”. I was walking around the venue with that badge and repeating, “Never mind, I am not an artist because I don’t think this place is a territory of art. There is no art here.” That was my standpoint, my performance.

That performance of mine continued when I came to a cemetery in Tashkent with another hand-made badge that said “I am an artist and I can answer all your questions.” Then I went to a bazaar with it. My message was that the territory of art was cemetery and bazaar. You can find numerous performances, still-lifes and readymades at a bazaar. A cemetery is filled with paintings, bas-reliefs, statues, marble figures. In other words, I was comparing that “territory of art” at the academy with a cemetery. But no one would ask me a question at a cemetery.