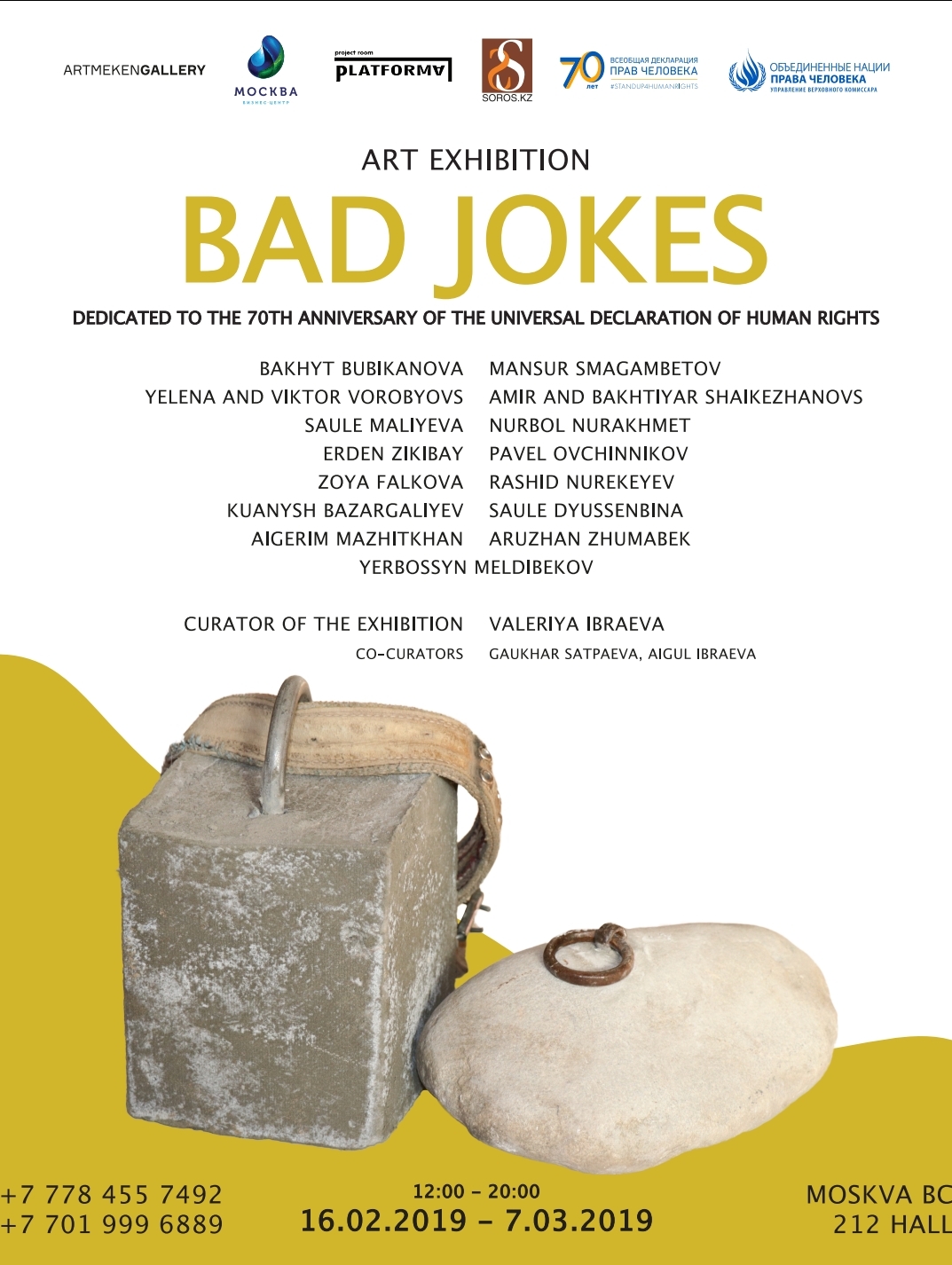

What? Exhibition “Bad jokes. Dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights"

Where? PlatformA Project Room (Astana, Kazakhstan)

When? from February 16 to March 7, 2019

ARTMEKEN gallery (Almaty) and PlatformA Project Room (Astana) with the support from Soros-Kazakhstan Foundation and UN Human Rights Office for Central Asia open the Exhibition “Bad Jokes” in Astana, dedicated to the 70th Anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The eponymous exhibition took place (also with the support of Soros-Kazakhstan Foundation and UN Human Rights Office for Central Asia) in Almaty’s ARTMEKEN Gallery from 6 to 26 December 2018 and was attended by over 330 people.

19 works of 16 Kazakhstani artists participate in the Astana’s exhibition; they include Bakhyt Bubikanova, Yelena and Viktor Vorobyov, Yerbosyn Meldibekov, Erden Zikibay, Zoya Falkova, Mansur Smagambetov, Nurbol Nurakhmet, Pavel Ovchinnikov, Rashid Nurekeyev, Saule Dyussembina, Kuanysh Bazargaliyev, Amir and Bakhtiyar Shaykezhanov, Aigerim Makhitzhan, Aruzhan Zhumabek.

The works are displayed in various techniques: video, ceramics, painting, installation, graphics, sculpture.

The exhibition’s curator: art critic Valeria Ibrayeva.

The co-curators are Aigul Ibrayeva (PlatformA Project Room, Astana) and Gaukhar Satpayeva (Artmeken Gallery, Almaty).

Below is Valeria Ibrayeva’s curatorial text.

“This exhibition had a great success in Almaty in December 2018. By the initiative of UN Human Rights and Soros Foundation and with joint efforts of the two galleries — ARTMEKEN and PlatformA, it is displayed in Astana, extended and augmented.

2018 in Kazakhstan was marked by powerful civil initiatives that were triggered by several dramatic events. The movements “We demand reform of the Ministry of Internal Affairs” and “Let’s Protect Kok Zhailau” united people who understood that the actions (or inactions) of the authorities were directly threatening their health and even their lives. The state’s desire and actions to limit opportunities for expressing dissent takes absurdist forms that Ionesco himself would envy. Internet blocking, blue balloons banning, ridiculous media trials, the “reform” of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which ended up with change of police uniforms, Denis Ten’s posthumous awarding with the medal “For Merits in Law Enforcement”, were perceived by the public as bad jokes bordering with mockery.

The exhibition “Human Rights: Twenty Years Later” held in December last year demonstrated that people of art did not consider themselves separated from the life of society, but, on the contrary, rather sharply reacted to situations arising in the country, fixating and summarising violations and distortions of fundamental rights. This year’s exhibition, opening ahead the 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is even more relevant — without saying a word, artists gave works ironically and satirically playing around certain moments that emerged in connection with violations of fundamental freedoms in Kazakhstan.

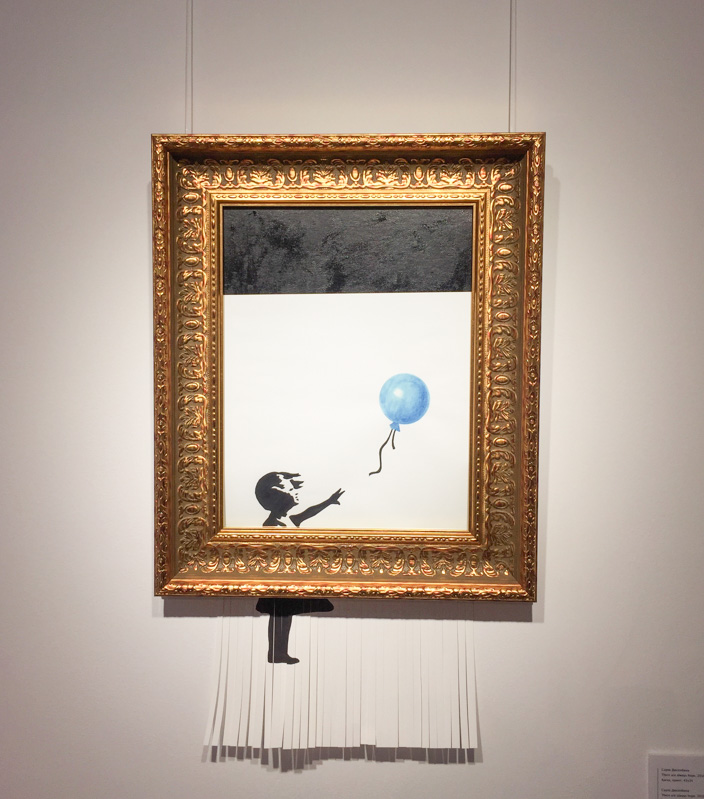

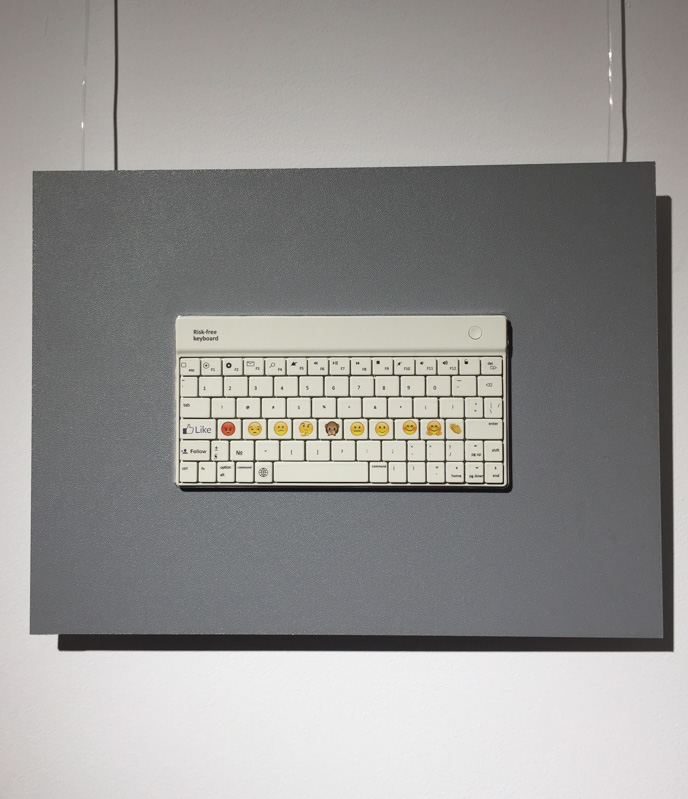

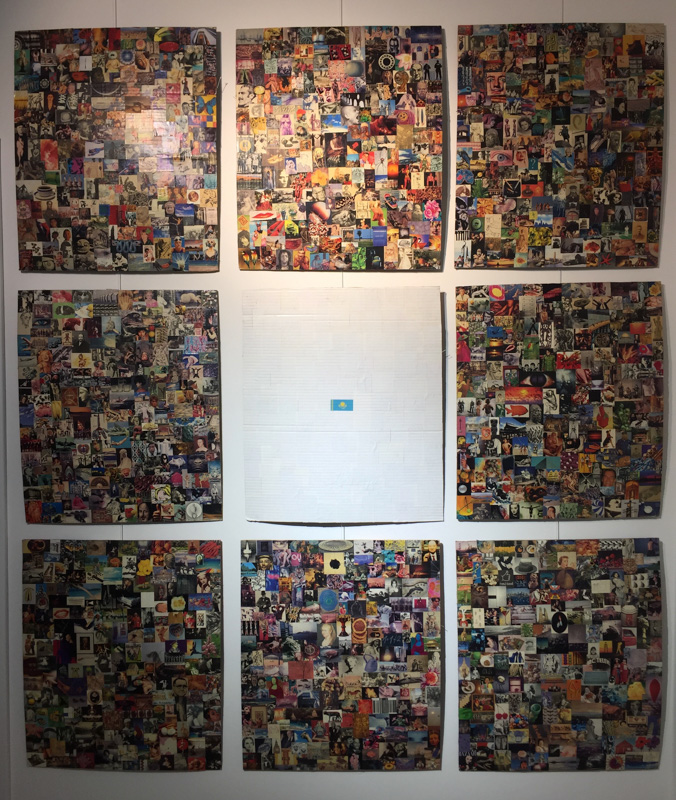

The master of collage, Pavel Ovchinnikov, in his complex selection of clippings from various printing materials shows how noisy and sociable the whole world is, entangled by electronic connections, networks, and contacts. The only square subject to total silence is Kazakhstan, in which Internet access is blocked without announcements but with sufficient regularity (Untitled, 2018). Therefore, in her video “Tom and Jerry” (2018), Bakhyt Bubikanova tries to hide from the eyes of an observer, climb into the mouse hole, cover her mobile phone, the source of information, with her own hands and body. Erden Zikibay (“Adas”, 2018) and Saule Dyussenbina (“There is always hope”, 2018) talk about children, affected by the spectra of attitudes towards them from outright cruelty to a simple, but inexplicable ban on an ordinary toy. For instance, Saule Dyussenbina almost literally reproduces the famous work of Banksy, recently sold at Sotheby’s with the scandal, changing the only small detail in it, initially the red color of the balloon is replaced with the forbidden blue. The idea of violence applied to children reaches its climax in the case of an attempt by adults to defend both children’s and their own rights. In the pictorial work “Constellation” (2018) of Nurbol Nurakhmet a monument to Abai erected on a pedestal observes from its height a map of Almaty on which like stars, dots flicker — places of “unauthorized” rallies. Yelena and Viktor Vorobyovs analyze situations and, more precisely, the positions in which the police find themselves dispersing people on the streets (Vintazh, 2018). They line up in a row or in a tight group, trying to cope with the resisting material — an old red blanket. Like Dyussenbina, artists sarcastically fix a moment of dull execution: the policeman does not care what needs to be subjected to “vintage” — a person, a blanket, a balloon. It needs to be grabbed, prohibited, taken away. The version of this graphic cycle, by the way, was a great success at an art fair in Dubai, and was almost completely bought up by Arab art lovers. The topic of a policeman chasing people is continued by Zoya Falkova in her parody of the black-figure ancient Greek painting. As a feminist activist she did not fail to invade the masculine world of ancient Greek sport, calling her work “Her own fault” (2018), a classic phrase that ends any clashes about domestic violence and attacks on women. A way out for all these situations is suggested by Rashid Nurekeev in the installation “The Other Side of the Wind. A hitching post” (2018) using the ancient device of the steppe to keep livestock at a certain place. The metaphor is obvious.

Even more sharpens the theme of the “fixed” person Erbosyn Meldibekov, using his old photos of people crushed by stones or buried in the ground in his new work. This series was devoted to research on the nature of violence and was called “Pol Pot (2000-2001). Fresh information from neighboring Uzbekistan about harassment of workers who did not fulfill the plan to pick cotton, forced the artist to recall the old series and continue with this, this time documentary images (The Invasion, 2018). A series of pretentious titles, of which there are quite a few at the exhibition, is supported by the sculpture of the artist from Astana Mansur Smagambetov. His “Breakthrough” (2018) is a whole squadron of planes assembled from flasks for water. In his work’s annotation, the artist complains about the lack of time to study rural children that are forced to constantly carry water from the stand-pipe for the needs of the family. The flask-planes, the artist’s ironic proposal to ease the work of children and give them the opportunity to learn, look especially well against the backdrop of the recent EXPO called “Energy of the Future”.

In 2019, the baton was picked up from the artists of Almaty and Astana’s M. Smagambetov and it was done by Astana’s artists Aigerim Makhitzhan (the installations “Trans-Siberian Express”, 2019, and “Qaraly Sulular”, 2019), discussing the youth issues and women’s place in Kazakhstan, Aruzhan Zhumabek (“Fragments”, 2019) whose series of placards directly illustrates articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and painter Saule Maliyeva who ingeniously placed on his canvas called “Axiom” (2019) bureaucratic soulless attitude to the person.”

Saule Dyussenbina

Mansur Smagambetov

Pavel Ovchinnikov

The hosts of “Bad Jokes” Exhibition in Astana express their gratitude to “Moskva” Business Centre for the support of the project.

Cover image by Nurbol Nurakhamet

Free admission.

Opening hours: from 12 p.m. to 8 p.m. daily

Address: Astana, 18 Dostyk Street, “Moskva” Business Centre

Contact details:

+7 701 999 68 86 Aigul Ibraeva (PlatformA Project Room, Astana)

+ 7 705 184 64 41 Gaukhar Satpaeva (ARTMEKEN Gallery, Almaty)