Adamdar/CA is launching the new special project — DOCA (Documentary Makers of CA) — dedicated to documentary makers working in the region of Central Asia and Caucasus and all kinds of documentary projects: film, photography, literature and reporting. The first DOCA profile is here to introduce Umida Akhmedova.

Umida Akhmedova, a photographer and film maker, is one of the most well-known documentary makers in the region. She was the first female camera operator from Central Asia.

In her work Umida explores the modern society of Uzbekistan and its current problems. Akhmedova’s documentary works helped the audience in Central Asia and other regions of the world discover the unknown people, places and processes in Uzbekistan. For her work and artistic principles, for several years during the President Islam Karimov’s regime Umida Akhmedova was subject to political pressure and prosecution.

In January 2010 Umida Akhmedova was accused of allegedly slandering and «insulting people of Uzbekistan». International support group that was created at that time to protect Umida Akhmedova initiated a petition in her defense. The petition had hundreds of signers among culture and media people — photographers, musicians, film makers, journalists, poets and artists from countries of Asia, Europe and America. Initiated by a documentary maker and «Novaya gazeta» columnist Victoria Ivleva, vigils in support of Umida Akhmedova were held in Moscow and Paris in front of Uzbek embassies under the slogan «Uzbekistan, be proud of Umida!».

In February 2010, due to a wide international public reaction and criticism towards persecution of Akhmedova, the judge released her from the courtroom saying that she was amnestied in honor of the 18th anniversary of Uzbekistan’s independence. Despite Akhmedova’s appeals to the Supreme Court of Uzbekistan, she still has not been officially exculpated.

In January 2014 Umida Akhmedova was prosecuted again — this time for being seen at a rally in Tashkent in support of the Euromaidan.

In 2016 Umida Akhmedova was awarded a Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent.

Umida Akhmedova is one of the bravest individuals in Uzbekistan and Central Asia’s cultural scene. She still works in Uzbekistan, she still works in the field of documentary, and she still continues to unveil the unknown stories of her country.

PARKENT

My name is Umida Akhmedova. I was born In 1995 in Parkent.

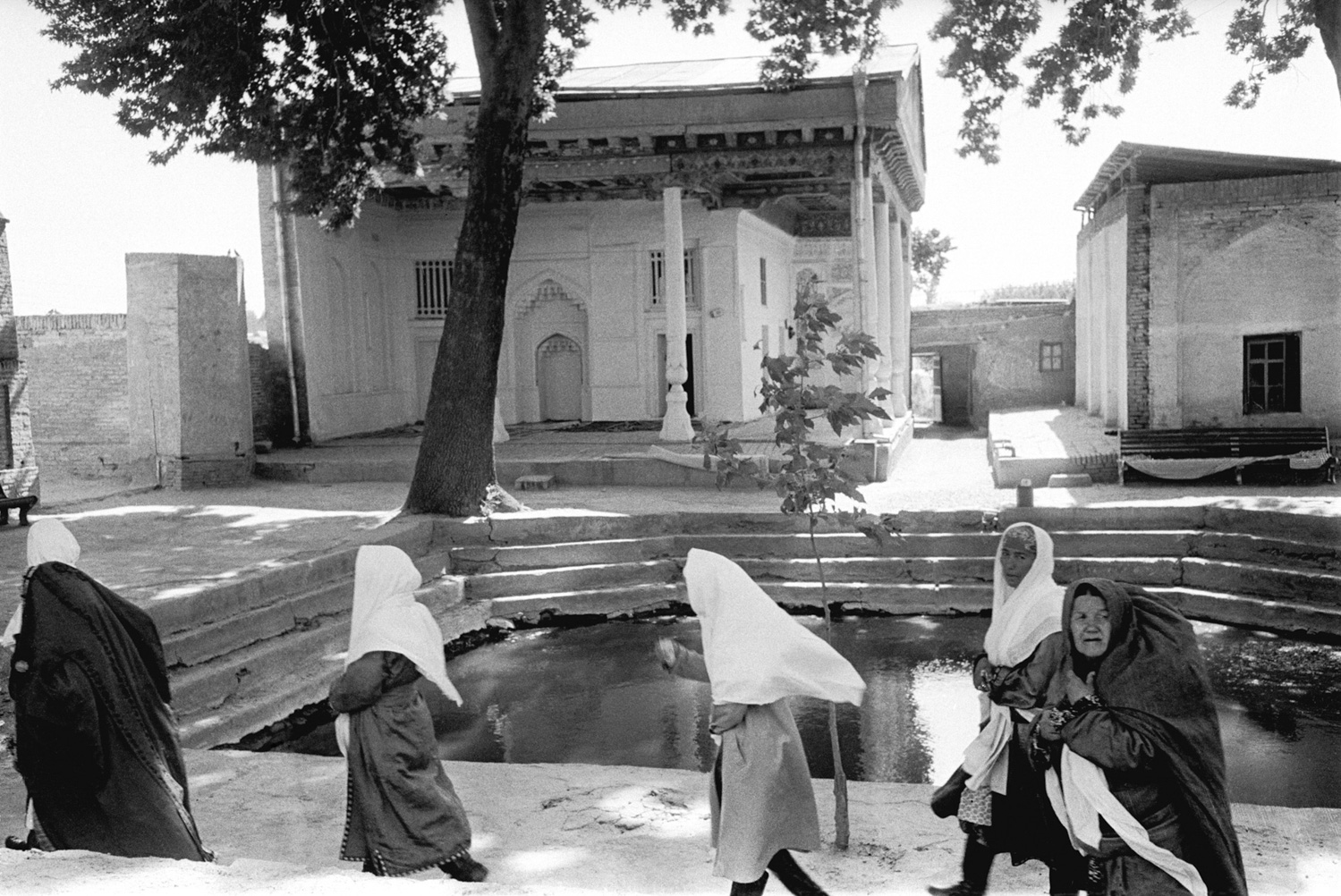

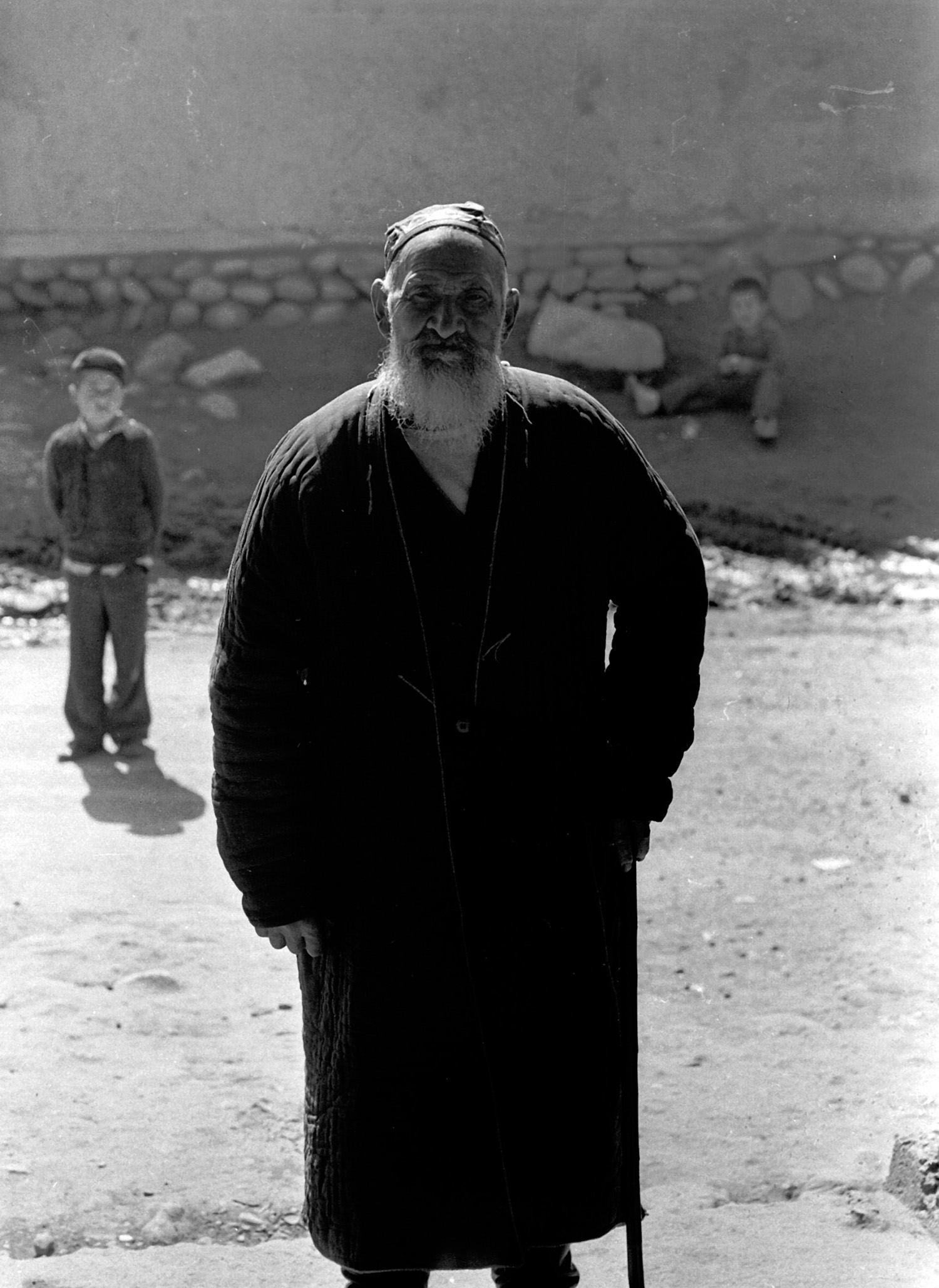

Parkent is a town in Tashkent region, 40 kilometers away from Tashkent. This place has been known for centuries as there is an ancient settlement underneath Parkent’s ground. Some cities disappear into nothingness as the years go by, but Parkent did not. It was always throbbing with life and growing. Now it is a vast and densely populated area.

Parkent has always been famous for its agriculture — fruit, vegetables and the famous “Parkent uzumi” (Parkent grapes — Å).

There was a strong influence of Kazakh culture in Parkent. Kazakh nomads always lived nearby. There are good grazing lands around the town — probably, that’s why Kazakhs used to stay on this land to raise cattle. So Uzbek and Kazakh traditions and cultures are interlaced in my hometown. For instance, in most of the regions of Uzbekistan people drink green tea while Parkenters always preferred black tea with milk — just like Kazakhs.

According to family legends, our family settled in Parkent in the 19 century, during the expansion of the khanate of Kokand. My ancestors were clergy members — they did missionary work, built mosques and were honored by the society.

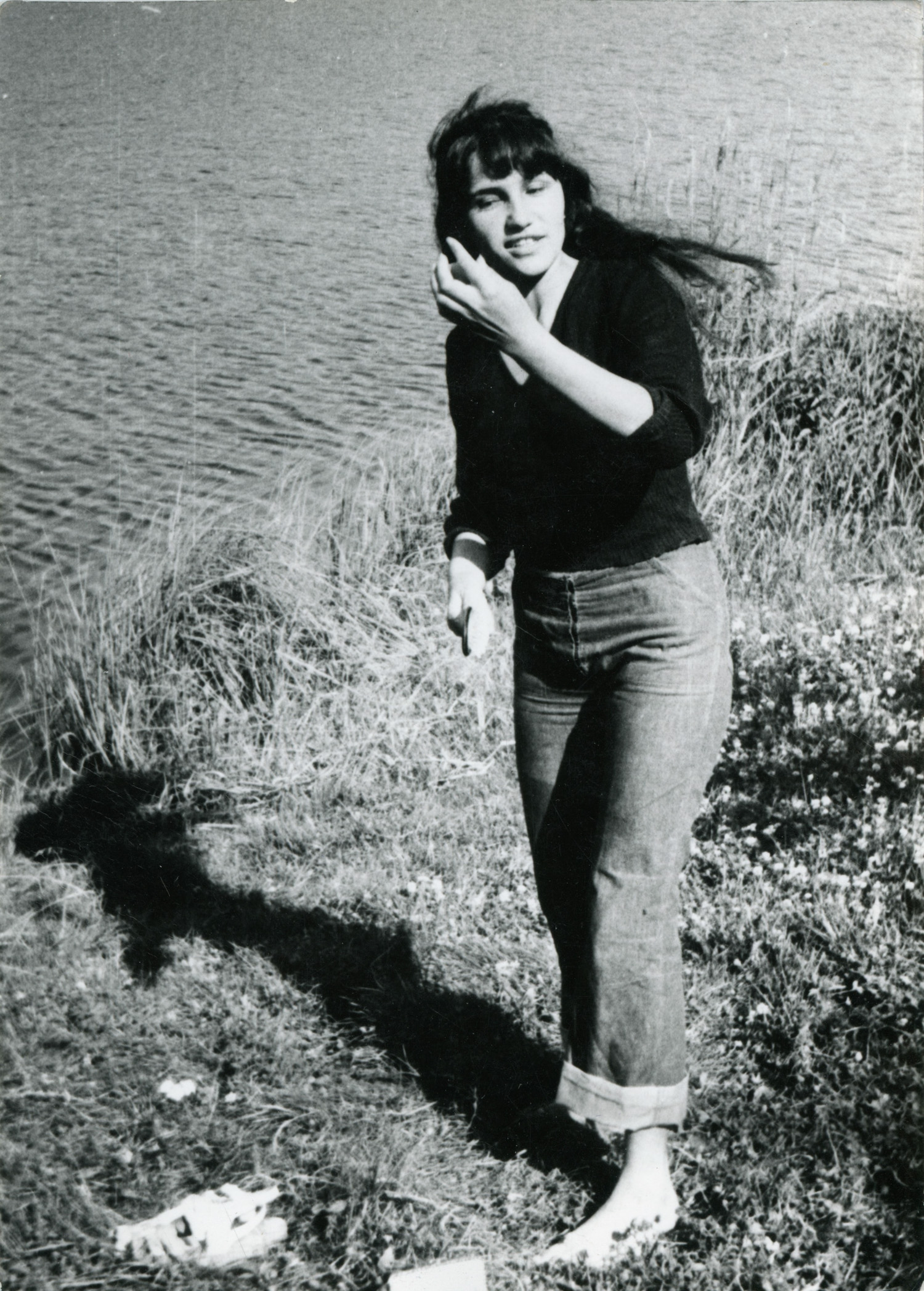

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

WAR

My father became an orphan when he was 12 and his brother was 4. Within 40 days they lost both their parents.

My father was eager to learn, so he finished a medical training college. My mother was very inquisitive, too, she wanted to study. But then the war began and interrupted their plans. My father left for the front, to save people…

During the war my mother received a condolence letter. It said that my father had gone missing in action. Everyone around would start crying, but my mother said, “He’s gone missing. He didn’t die. He’s alive and will come back…” Mom waited for dad. Dad returned from war.

PARENTS

My father went all the way through the war. He left in 1939 and returned as a medical officer in 1946.

Just like many veterans, dad didn’t like to talk about the war.

Some soldiers brought things, some kind of trophies, from the war. But my father brought a different kind of mindset.

He left for the war as a very young man and got to see different places and cultures — a different world. Despite the atrocities of war, as a thinking person, as a man of great culture, my father could clearly distinguish between Germans and Nazi. He discovered European culture for himself — and fell in love with it. Dad always loved classical music and knew how to dance all those waltzes and foxtrots. That’s the kind of man my father was.

My mother was an interesting and peculiar person — very well-read and romantic. Also, she was a woman of faith and had an uncanny memory. She could tell, by heart, hadiths of the prophet and surahs from Quran to her friends for hours and hours.

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

I will be ever grateful to my parents for their kind and delicate attitude towards me

There is a woman I know. She married a Russian man. After the wedding she told me, “My father won’t talk to me anymore because I married a Russian.” Her father, an Uzbek, was a big wig in Tashkent, and her mother was an intelligent Russian woman, but nevertheless, the father cast off his own daughter because she chose a Russian man. Despite belonging to the political elite and holding a post in the Communist Party, despite the fact that it was the 20th century, his mindset remained somewhere in Middle Ages. I was lucky to have parents like mine. They would always be understanding, supportive and proud of me and my work. When I married Oleg, a Russian man, they accepted my choice. So I will be ever grateful to my parents for their kind and delicate attitude towards me.

Image by Malika Autalipova

ANGEL

I became a documentary maker by chance.

I made several attempts to get into Moscow State University’s School of Philosophy. Thank God I didn’t make it! I have my personal angel — Albina. She is my old friend, a native of Vladimir region, we met when we both tried to enroll at the university for the nth time. And that time we didn’t score enough points again.

I stayed in Moscow. That period of my life was really hard, but being a stubborn person, I decided that it was not until I got an education that I would come back home, to Uzbekistan.

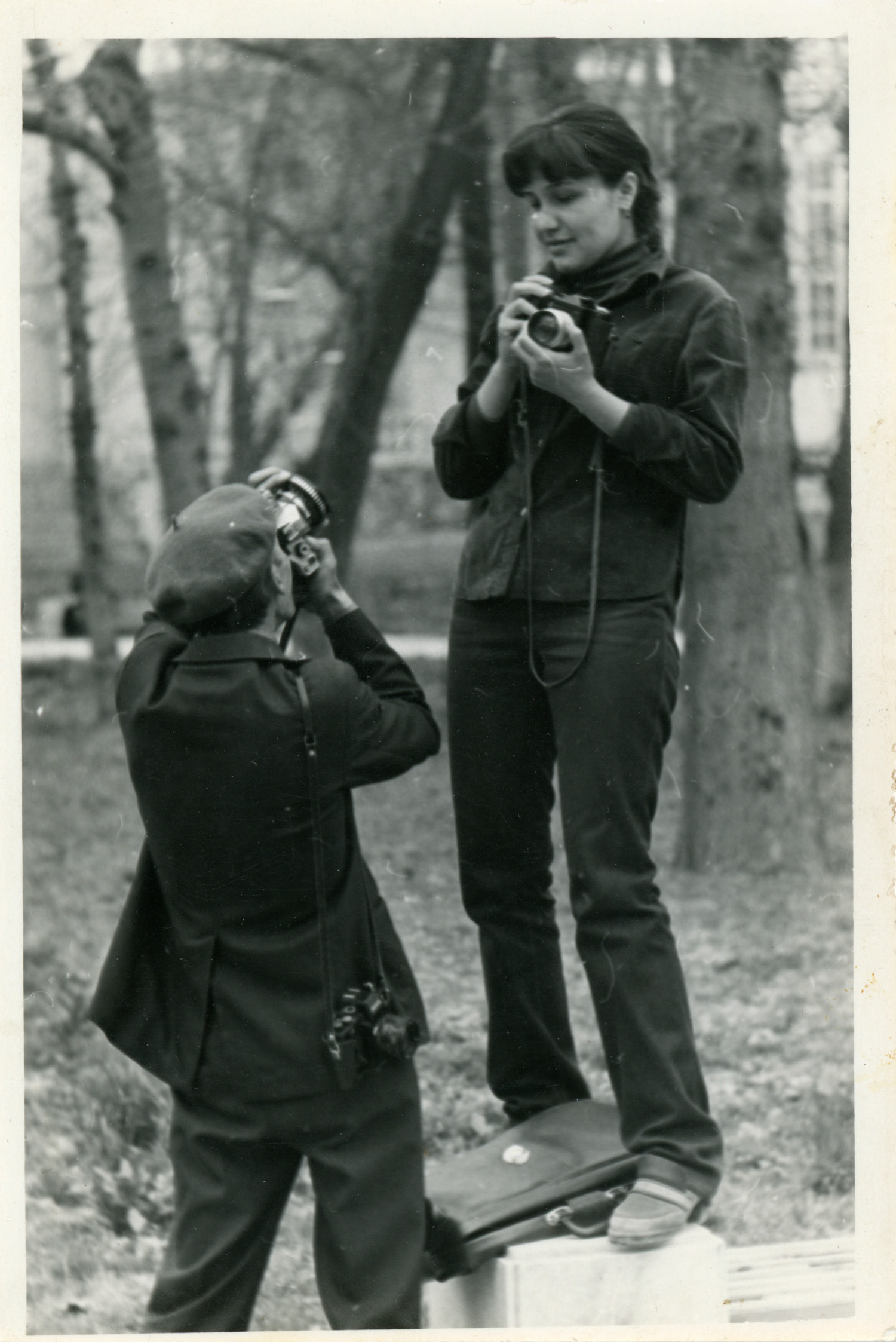

Then Albina told me about the Cultural and Educational School in Vladimir. That school had a Film and Photography department. So I ended up in Vladimir… I still remember those brand new FED cameras we were given. Eventually, Albina enrolled at MSU’s School of Philosophy, and I said, “No, I don’t need the School of Philosophy anymore. I’m staying in Vladimir.” That was the time when I decided to cast my lot with filming. I don’t know what my life would’ve been like if Albina had not appeared in it. That’s why I call her my angel.

There hadn't been a single female camera operator in Uzbekistan or any other Central Asian republic before

In Vladimir I decided to become a camerawoman. It was a no ordinary decision, because there hadn't been a single female camera operator in Uzbekistan or any other Central Asian republic before. I went to Tashkent for a break. There I met Malik Kayumov and told him I wanted to work as a camerawoman. “Then you’ll have to go to VGIK,” he said.

Getting to VGIK was not an easy thing to do. But still, I got my degree there. There had been girls from Central Asia who had graduated from VGIK before me — movie scholars, directors, script writers, actresses, but I was the first female camera operator. So I became the first professional camerawoman from the Asian part of the USSR.

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

UZKINOKHRONIKA

If you want to do what you really love and value, you’ve got to always remember what your goals are and fight for them. Study and work in Russia and Uzbekistan. Leave and come back again. I had to overcome fears inside me and stereotypes around me. I went through empty pockets and rejection. I struggled to make ends meet, something worked, something didn’t… But it was back then when I realized how important it was to have a goal in your life and to follow it. I could stay and work in Moscow, but I always wanted to shoot in my native Uzbekistan.

At first, when I came back to Uzbekistan, it was hard to find a job. I had neither clout nor influential relatives. So I had to do everything myself. It was difficult to get hired because at that time it was really important to have good connections, and I had none whatsoever. Besides, I was the first female cinematographer, so I could feel that hidden distrust of me and my abilities.

But I didn’t give up and just kept working. I went all around Uzbekistan and filmed. When my colleagues saw my works, they finally realized that I was capable of shooting films.

In Central Asia only Uzbekistan had a separate documentary studio. All other national film studios had only documentary divisions, e.g. Kazakhfilm, Tajikfilm, etc. But we had a whole documentary studio — Uzkinokhronika.

I started as a camera assistant, then worked as a camerawoman. Uzkinokhronika was the place where I worked for the longest period in my life. I worked there for 14 years and shot about 20 films.

During the years of “perestroika” in Soviet Union, they opened a window slightly. We could feel changes and freedom… It was a wonderful period for documentary making, for creativity. Golden years. We learned a lot, worked a lot and shot a lot. But then the window was shut again…

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

THE GIRL WITH A CAMERA

In the days of my youth people in Uzbek province would give a girl with a camera the same look they gave a few decades earlier to our grandmothers when they started to take their veils off.

When I came to Parkent and started shooting, many adults would start laughing at the sight of a girl with a camera.

But the aksakals — veterans, same age as my father — were supportive of me. They would say, “Keep taking pictures, dear, don’t pay attention to them.” That’s how I got my blessing to documentary making. That’s how I started to shoot…

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

From Umida Akhmedova's personal archives

(Umida Akhmedova’s story will be continued in the upcoming issues)