Lukpan Akhmedyarov is a journalist, civic activist, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Uralskaya Nedelya (Uralsk Week), and creator and author of documentaries. He is one of the best journalists in the country, a living symbol of professionalism and civic courage within the independent media of Kazakhstan.

Akhmedyarov has held several civil campaigns in defense of rights and freedoms. He was repeatedly subjected to provocations, unconstitutional detentions and arrests. He survived an assassination attempt. For civil courage and protection of the principles of independent journalism, Akhmedyarov received the Peter Mackler Award, awarded by the international human rights organization Reporters Without Borders.

Akhmedyarov shared with ADAMDAR/CA thoughts about his childhood, his first steps in journalism, and about his city and his country.

CHILDHOOD

I was born on the shortest day of 1975 – December 23. I am the fifth and last child of my parents – a rural site supervisor and paramedic.

Since I grew up in a large family, I did not enjoy many of the special moments that come with “traditional” Soviet childhood and youth. In particular, in childhood, I didn’t have my own bike, and in my youth, I lacked a guitar, tape recorder or moped. All this was acquired by my older brothers, and I received their hand-me-downs. If you had seen the condition in which my brother Askhat’s “Romantic”-brand tape recorder was in by the time it reached me, you would have understood that the tape recorder’s life experience was richer than mine.

My family and I lived in the village of Novopavlovka, forty kilometers from Uralsk. Novopavlovka is a village densely populated with ethnic Ukrainians, and my first childhood memories were made there. After Novopavlovka, we moved to the village of Aksuat. A Russian family lived in Aksuat next to us – a teacher and her elderly mother. My mother visited their house for more than three months; the elderly woman was dying from some serious illness, and my mother came to give her injections every evening. When I first came to this house, I saw that the whole space was filled with books from floor to ceiling, starting from the entryway and ending with the living room in the back of the house. I experienced there something similar to what Alice felt in the Looking Glass. I began to go to this house with my mother every day. While my mother eased the torment of the dying woman, every day her teacher daughter little by little taught me to read. At the age of five, I read my first books.

The whole space was filled with books. I experienced there something similar to what Alice felt in the Looking Glass.

In our village there were only two people who read the books in the school and kolkhoz library. The first of them was my neighbor Kuanysh. He was three years older than me. And the second reader in our village was me. Kuanysh, by the way, was the first to introduce me to the concept of human rights. When I was in seventh grade, Kuanysh was expelled from the Komsomol for some reason. Later, it became clear that in a social science lesson, he had driven the teacher into a dead end by saying that any state, including the USSR, was always an apparatus of violence.

LETTERS

My passion for writing didn’t appear instantly. The very first milestone related to the process of creating text was when I wrote an essay in school that brought me schoolwide recognition.

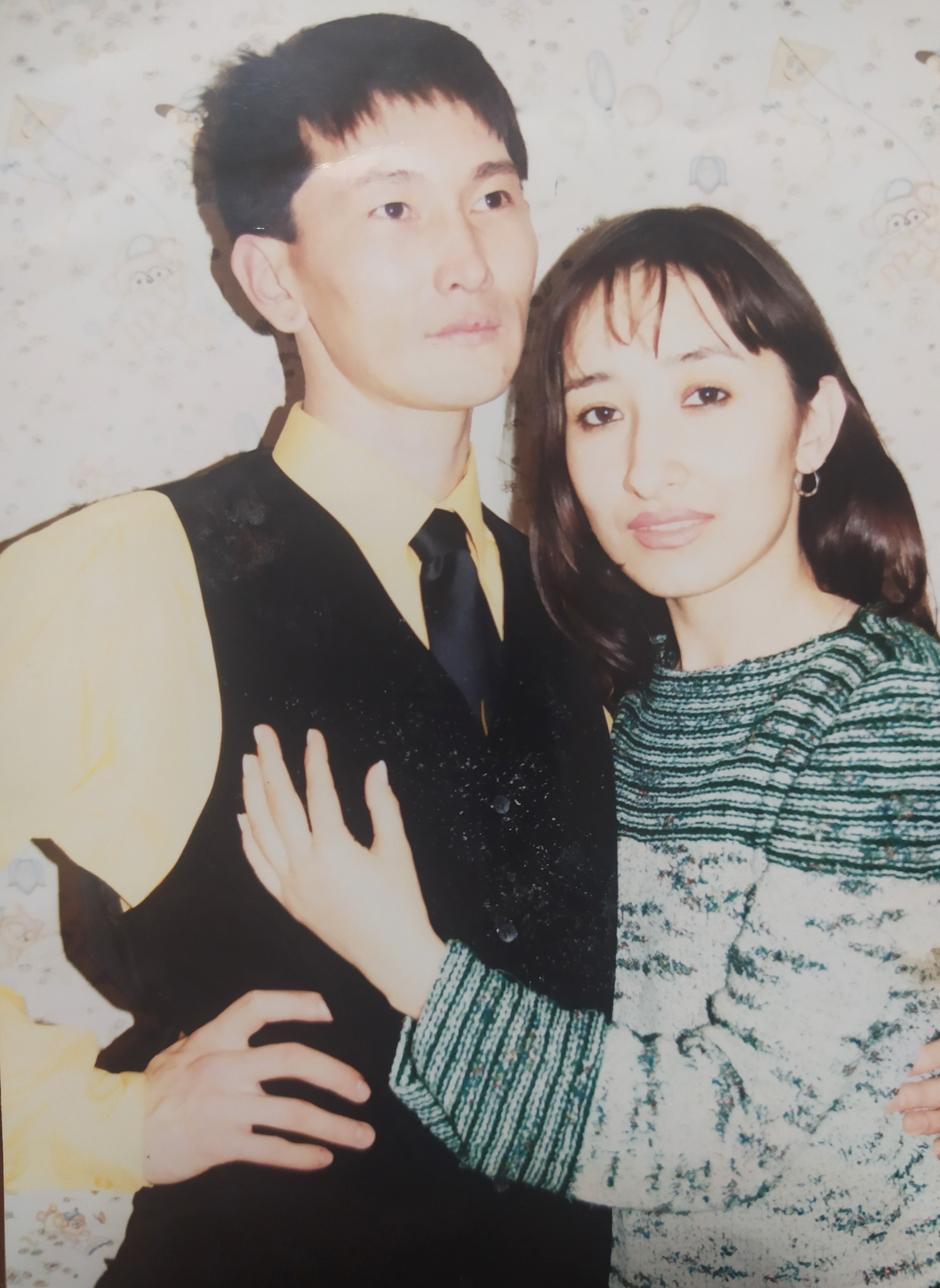

I met Aigul at the institute. I fell madly in love with her, courted her, ran after her. In my fourth year, it seemed to me that my love would remain unrequited, so at some point I went to my village and wrote her a letter. The letter was long, fifty-some pages, and was probably my second milestone in writing. I received a wonderful reward for writing that letter: I married this girl. We got married 10 years after our first meeting. Now we have two daughters: Aruzhan and Rania.

Askhat Akhmedyarov is a famous Kazakhstani contemporary artist, author of resonant art projects and performances. He has led multiple civil and art actions fighting for democratic principles and against political repression.

RURAL TEACHER

In 1996, I graduated from the institute and got my first job at a station for young campers. Having received my first salary in the form of two bags of onions, I quit. I returned to my native Aksuat and began working at a school as a teacher of geography, biology, and, for some reason, history. I worked at the school for four years. During these four years, I was always on the director’s nerves because I refused to subscribe to the regional and district newspapers. In my fourth year I finally gave in and subscribed to the newspaper “Speed-Info.” This did not make the director very happy, but it absolutely delighted our military and physical education instructors.

I made the decision to leave the school myself. Three months after leaving, I heard on the radio that a private independent newspaper was being opened in Uralsk. I arrived at the address that had been announced. It was then that for the first time I saw Tamara Yeslyamova. She asked if I had any experience in journalism. “Yes,” I lied. “Great!” said Tamara, and gave me some kind of press release that needed to be rewritten into a suitable format for the news. When Tamara saw me agonizingly typing with one finger on the keyboard, she realized that I was not an experienced journalist, but she did not fire me. Instead, she handed me a volume of “War and Peace,” sat me down at the computer, and ordered me to retype it. By morning, I had reached the middle of the volume and relatively quickly began to type with both hands. Thus, I became a journalist.

ARRESTS

The first time I was detained was in 2008. This happened because here in Uralsk, the oblast akim filed a lawsuit against a public figure, accusing him of slander. We, the journalists who wrote about this, were brought to court as witnesses. I came to court and said that I did not want to participate in this buffoonery. They locked me up for five days for, as they put it, contempt of court.

The second time I was arrested was on December 23, 2011. Sanat and I were going to celebrate my birthday. And just then information came out that in Ust-Kamenogorsk some elders had taken the initiative to give President Nazarbayev the opportunity to be elected an infinite number of times. They started invoking the title “Leader of the Nation.” Judging by how actively state media began to spread this info about, I realized that this was not just someone yakking on about some nonsense. It became clear that a deliberate campaign had begun to legitimize all this. We waited for several days to see how the Kazakh opposition would react. We waited for someone to come out, for rallies to begin, and so on. But no one came forward in opposition. Everyone was watching these events and taking them in silently. So Sanat and I decided to go out to demonstrate on the square.

We made two posters, and so that they would not be torn from our hands, we sewed the posters to the jackets. Sanat’s poster read “A person cannot live on NAN alone”, and it featured a depiction of the president in the middle of a wheat field. And I had a picture of the president photographed with a bundle of money at a tenge presentation with the inscription: “Nazarbayev is my president, and there’s nothing I can do about it.” We went to the square, and they arrested us there. We were detained and taken to the police station. They wanted us to be taken to a special detention center on the same day. We did not allow this to be done and began to resist in court — not physically, but protecting ourselves verbally, legally. Experience working with the local human rights bureau helped me a lot in this moment. Human rights activist Pavel Mikhailovich Kochetkov taught me a lot: I can say that, thanks to him, I have an unofficial law degree. We argued with and defended ourselves in front of the court for a long time, but they still put us in jail for 15 days.

We began to resist in court — not physically, but protecting ourselves legally

When I first entered my prison cell, the very first thing I noticed was a scary plastic bottle on the table. It had been mutilated with melted and burned edges. I ask my cellmates: “What is this?” They replied, “These are our dishes.” It turned out that the detained were given neither metal nor plastic dishes. Those who were serving their sentences were sent mineral water when they were first jailed. The prisoners drank the water, and since they were not given a knife, they took a lighter, melted the bottle and divided it in two. This is how they managed to make “dishware” from which they drank. I was shocked.

Then they brought us some so-called “food.” I looked at the horrible gruel and refused to eat it. I demanded a pen and paper from the guard on duty and started writing a complaint. The cellmates didn’t like what I was doing, and they asked: “Why do this? We’ll be punished —they’ll withhold boiling water from us.” And boiling water, as I understand, is one of the most valued items in enclosed places. But I didn’t give a crap about boiling water. The prosecutor on duty read my complaint and heard me out. That same evening, instead of gruel, we were brought rice with chicken legs and fresh juice. It was served in normal dishes. My cellmates were surprised, to put it mildly. The remaining time in custody was spent productively: I taught my cellmates how to correctly and competently write legal requirements and complaints. Thanks to this, we had our toilets, bedding, and other items successfully replaced. On the third day we were taken outdoors for exercise. In the corridor, the head of the special detention center passed me and said: “Goddamn it, Akhmedyarov, when are you gonna get outta here? You’re causing me so much grief!” I told him: “I didn’t force you to work in this system.”

I taught my cellmates how to correctly and competently write their legal requirements and complaints

SOCIETY

I perceive key events for modern Kazakhstani society through a personal lens. The first event in my life that greatly influenced my worldview happened when I was in my fourth year at the institute. The administration gathered our entire group to tell us that we all needed to join the Otan party. Back then it was not called “Nur Otan.” Even at that time, it did not sound like recommendation, advice or request; it sounded like an insistent demand. One of the teachers stood up and said: “We just bid farewell to totalitarian communism, and now are we going back in that direction? Are we going to herd the students into the party, like it was with the CPSU, or what? ” I remembered this speech. This was a historical moment: that was when the consolidation of power began, where everything was subordinated to the interests of Nazarbayev.

I perceive key events for modern Kazakhstani society through a personal lens

The second very important event was my first election to local government. In 2006, elections were held in local maslikhats, and I decided to declare my candidacy. I registered, formed a campaign staff, printed leaflets, went to polling stations, and held meetings. My opponent in this election was a man from Nur Otan, and he was clearly losing. Firstly, he was deprived of any oratory skills. More precisely, he didn’t know how to speak adequately whatsoever. Secondly, he had been a deputy for a very long time in this district. Witnesses counted the ballots and the numbers showed that I had prevailed. In the middle of the night they called me and informed me: “Everything is cool, you won!” However, in the morning, the Central Election Committee announced the results, according to which 80% of voters in my constituency allegedly voted for the candidate from Nur Otan and 20% for Akhmedyarov Lukpan. I was outraged, we sued, I tried to initiate a recount. But the case was closed. The situation was a clear demonstration of how the will of the people is nothing but a doormat upon which Nur Otan wiped their feet. It was then that I experienced and realized in my core how terrible a crime election fraud really was, an insidious crime against society and against the state.

Another important event that influenced my opinion on society, the state, and the situation with freedom of speech in our country was the murder of journalist Askhat Sharipzhanov. I still believe that this was a planned murder, although authorities claimed that it was an accident and that a car had accidentally hit him. And then the alleged suicide of Zamanbek Nurkadilov and the punishment of Altynbek Sarsenbaev followed. I realized then that the forces in power had flown off the rails and we were rolling in a very scary direction. It became clear that the authorities were ready to kill and that they considered it normal. And there was no greater confirmation of my realization than what happened on April 19, 2012, when I found myself the victim of an attempted assassination.

ATTEMPTED ASSASSINATION

I am convinced that this was an assassination attempt, although the police and prosecutors have repeatedly stated that in reality it was “just an act of intimidation.” But I still think it was an action taken with the intent to kill me.

The way everything started couldn’t have been any more bloody ordinary: it was dark, I left my house, went to the store, and returned home. I held a flashlight in my hands. I walked calmly, shining the beam ahead of my footsteps, and noticed that two guys were sitting in the yard of my apartment building. I did not shine my light upon them; on the contrary, I moved my beam away from them, because it is rude to shine light on people’s faces. When I walked past them, I heard the words: “Mynau ghoy” (Kaz. “This is him”). I turned around and heard the shuffling of feet. I realized then that they were running towards me, and then the first shot rang out. I saw a flash from a gun, and I felt a terrible pain. I grabbed my head, and at that moment I had no fear, only a terrible indignation. “What the hell do you think you’re doing? Have you lost your goddamn minds?” I started to fight these two men. A second shot rang out in the dark, but I was flush with the fever of adrenaline and didn’t feel anything. As it later turned out, this bullet hit my elbow. One of the attackers fought strangely: he came up to me, beat me with one hand and stepped back. It became clear that he had a knife in his hand that I did not notice in the dark, and he was stabbing me with it. In a fight, somersaulting, we rolled to the playground near the entrance, and there was lighting there. As soon as the men were illuminated, they sprung up. One ran away immediately. The second tried to run away, but I knocked him down and we started to fight again. He eventually managed to wrestle free and disappeared. I ran towards the entrance of my apartment building.

I still think it was an action taken with the intent to kill me

When I got inside, the first thing I saw was a guy and a girl who were standing there kissing. Seeing me, the girl began to scream terribly and very, very loudly. I was covered in blood. She screamed so loudly that my ears started to hurt, so I grabbed my head to cover them, and only then realized that blood was flowing from everywhere. At the sight of my own blood I was truly and terribly scared. My legs weakened, I went out in front of the entrance, and fell. The neighbors ran out, laid me on a bench, administered first aid, and called an ambulance.

UNDER THE TABLE

After the attempt on my life, I recovered surprisingly quickly. Even the doctor said I heal strongly and quickly like a dog. After just 21 days I was already discharged.

After the attack, when I was still recovering and lying in the hospital, I was called and asked to give an interview. I was asked about who ordered the assassination. I said that I had no idea who ordered it, but most likely someone about whom I wrote and in whose throat I had lodged myself. At that time, I already had very actively begun to cover the topics of public procurement, corruption, and elections. Someone in power didn’t like it, so the decision was made to have me killed. And I still don’t know which authority exactly gave this command. But even at that time, I suggested that the execution was outsourced to someone who, most likely, was not at all aware of my activities. They were simply given money to do what they were told. I joked that, knowing our Kazakhstan, where everything is built on ‘otkat,’ secret, under the table payments, I would not be surprised if it emerged that there was corruption in the relations between the public officials who organized this assassination and its perpetrators.

Later, when they found the perpetrators, a confrontation took place. I asked them how much they were promised. Ten thousand dollars, they replied. Then I asked them how much they ended up with, to which they said, “We received 100,000 tenge ($684 according to April 2012 exchange rates).” Then, after some time the organizer of the attack was detained and tried separately. At the trial, he refused to give the name of the hiring party, and still has not named him. But he let slip that initially $50,000 was promised to the hit men. It thus became clear that they couldn’t even attempt an assassination without shady deals, unfulfilled promises and corruption.

KAZAKHSTAN

In my opinion, what has been happening in Kazakhstan in recent years in terms of freedom of speech and human rights is a systematic tightening of the bolts. It is getting worse and worse. About ten years ago, when a policeman would come up to me, or when they would detain me, I could defend myself by using the law and ask a government official: “On what basis are you detaining me? What law have I broken?” These questions perplexed them, and sometimes they successfully stopped the police officers. Now, nothing stops them. They don’t bother themselves with the law and do not give a person the opportunity to voice their questions. They obtusely detain you, violating the most basic rights and laws. The system, this whole army of policemen, is ready to carry out such orders without caring about your rights or the Constitution. Since last year, not only journalists and activists have been vulgarly seized and detained, but also ordinary teenagers, women, and passers-by. Authorities no longer show even minimal respect for human rights and the law. They do not worry about it at all. They are only concerned about holding on to power.

At the beginning, when I had just started doing journalism, I was flattered by the fact that reputable people were in possession of my articles, including some officials who recognized me. It was such a youthful buzz. Now, I feel no such feeling. Whenever I am called to court, or when a new provocation is arranged against me, or when I am put in prison for fifteen days, at such moments, of course, I think: “To hell with all this...I have to go somewhere to Europe, or, I don’t know, move to the States and live there peacefully. And then, when everything settles down, you return to work as usual and at that moment you think: “Damn it, yes, of course I could leave, but I truly want to change something here. In Europe and America, several generations of citizens have already changed things for the better without me there, but here, in Kazakhstan, there is so much work, the fields are uncultivated!” Therefore, for me, Uralsk is not just my hometown. This is a city in which I feel that I can create something, change something. Over time, it became clear that with the help of my work, with the help of texts and publications, I can influence something, change something in this city, in this society, in this country.

Damn it, yes, of course I could leave, but I truly want to change something here