Paul Salopek is a distinguished American writer, journalist, documentarian and explorer. A two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and National Geographic Fellow, he created a unique project called Out of Eden Walk.

Out of Eden Walk is an unprecedented transcontinental 21,000-mile odyssey along the migration route of the early humans. Paul Salopek will take over a decade to walk the route in its entirety.

Salopek has been on his one-of-a-kind journey for seven years now. Along the way, he gets to know people and territories, writes, takes photos and videos. He is working on a book about his journey. He started in Africa, continued through the Middle East, passed the Caspian Sea and the mystical landscapes of Mangystau, walked the roads of Uzbekistan, crossed the high mountain passes of Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic, and left his footprints on the streets and in the ravines of Pakistan, Afghanistan and India. We wrote to Paul Salopek as he takes a pause in Myanmar.

Specially for Adamdar/CA, he shared his reflections on how the COVID pandemic will change our culture and perceptions of the world, talked about the three main environmental problems of Central Asia, and advised storytellers and other authors how they might adapt to our new reality.

© Paul Salopek

Questions: Malika Autalipova, Timur Nusimbekov

In your project, you are following the ancient pathways of human migration, and for years you have been studying history, as well as the modern world. In your view, what place does the present situation with COVID-19 pandemic take in the history of the world: would it be appropriate to compare it with other historical cataclysms, or is it unprecedented?

Every historical event is unprecedented. And the first adage of the professional historian is not to use the past to predict the future. If you try, you just end up projecting your own knowledge gaps and biases onto a blank slate.

If forced into this game, though, and since I'm not professional at all, I would speculate on the side of epic changes. Pandemics upend far more than public health. Look at the existential disruptions in Europe brought about by the arrival of bubonic plague along the Silk Road. It eroded faith in the power of the Church of Rome, helped bring down feudalism, and accelerated the rise of mercantilism and cosmopolitanism, and maybe, eventually, stoked the Enlightenment. (Check out the Decameron, a 14th-century tale of young Florentines self-isolating in a villa and swapping amusing stories that poke fun at corrupt monks, while extolling the savvy qualities of a new class of people—sophisticated urbanites who aren't landed aristocracy: 14th century hipsters, essentially.) Covid-19 isn't comparable in the least to the Black Death in terms of mortality, of course. But the human condition today—an extraordinary and complex level of global interdependence unseen in the story of our species—will magnify the pandemic's effects on a profoundly disproportionate scale. One way or another, this pandemic will touch everyone alive today, thanks to globalization. Much of the result will be tragic. But I try to take heart that with massive trauma comes a new alertness—perhaps in this case, a heightened awareness that our lives are truly interlinked, and therefore must be valued everywhere.

One way or another, this pandemic will touch everyone alive today, thanks to globalization

Human beings aren't good at big systemic changes for the common good. We're selfish, myopic, tribal. But maybe a ruthless virus can help jolt us awake. In that broader sense, and not just medically, this may be more than a “once-in-a-century” change event, dating from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. It could be more like a once-in-500 year event. We'll see, soon enough.

© Paul Salopek

Out of Eden Walk is a unique experiment in slow journalism. Today, in the world of instant news, live streamings and social media, what do you see as the greatest value of your approach?

Look, I step onto the “fast news cycle” merry-go-round, too. I use social media: I gather ideas from it. So the Out of Eden Walk project isn't anti-technology. It doesn't claim to be a miracle elixir or cure-all for the countless problems of our digital age. I think of it instead as a calmer, quieter island in the stormy oceans of online information, in the furious and largely incomprehensible hurricane of factoids, memes, distractions and billions of randomized, fragmented stories that now wash through our lives via our phones: pixels, fractals, raw data. The project is an invitation: Swim ashore on this atoll. Take a walk. Experience current events at a more human level—at boot level—more slowly, at five kilometers an hour, a pace that our brains have evolved over 99.9% of our species’ history to absorb stimulus. I always say that the walk's storytelling is about meaning, not just information. Each of the walk's stories is connected to the next. It's a narrative journey, just as each of our lives is a journey. We're wandering creatures by nature. The walk taps into that old yearning. If the project has any value, it's in that humane context: sharing the trails that connect us all.

We're wandering creatures by nature. The walk taps into that old yearning.

© Paul Salopek

© Paul Salopek

© Paul Salopek

You have visited many countries, seen so many different people and walked thousands of miles. You have seen the world and the people change — before the coronavirus and during this pandemic. Do you think that the methods, forms and the whole idea of migration that we are used to will change after the pandemic ends?

Definitely. I think it may be years before we return—if we ever do—to the fluidity of travel we experienced in the pre-pandemic world. That includes privileged people moving voluntarily—either for official, well-paid work or for play—and those moving involuntarily, often illicitly, pushed by poverty or war, and pulled by necessity. What the economics of this new lockdown world will look like is hard to say. In a long interim, it's likely to be quite a bit poorer overall. The old global order was built on the relatively free movement of goods and rich people. (Poor labor was either bottled up or exploited as undocumented migrants.) What comes next with hardening borders? I'm waiting to see native-born anglo-Americans, especially those who enthusiastically support billion-dollar border walls, manually picking crops during the summer in the Central Valley of California. That will be quite interesting. As an itinerant farm laborer, I've picked pears, grapes and tomatoes. Oranges are the worst. There's the tree thorns. And nothing is lonelier than the sound of the first orange gonging into a gigantic steel bin. Twenty-eight dollars a metric ton. That was the day-labor rate in my day.

I think it may be years before we return—if we ever do—to the fluidity of travel we experienced in the pre-pandemic world

© Paul Salopek

What are the biggest delusions and/or stereotypes around the coronavirus that you notice in the information flow or in conversations with people?

Apart from stupid conspiracy theories? That it's a national or even local problem. Tribal zero-sum games. For example, that Covid-19 is China's “fault” and thus you can disengage. Or, that once Kazakhstan gets its medical protocols in order, the problem will go away for Kazakhs. Or, that whatever horrors the pandemic inflicts on Sub-Saharan Africa's countries, where a billion people live, that's their problem. Good luck with such magical thinking. When your company or industry needs parts from Thailand or ingredients from Ghana, what transpires in those countries spells your survival or doom. The alternative may be more domestic self-sufficiency. If so, we're talking about a reordering of the global economy that is going to be generationally agonizing.

© Paul Salopek

© Paul Salopek

What do you think are the most dangerous consequences of the pandemic?

Xenophobia. Nationalism. Bigotry. More othering. Not rising to the occasion. A lack of charity.

What are the key lessons that humankind should take from the current situation in the world?

Stop over-planning your life so much.

© Paul Salopek

Today, people around the world are in lockdown, unable to maintain their usual lifestyles. How can storytellers, who are often used to traveling and seeking stories out in the field, adapt to the new reality and continue telling the stories while staying at home?

I've always suggested to journalism students that it's easy to jet off to some war and make your name covering such dramatic material. It's actually the most unimaginative, even lazy, way to success. And I say this as a former war reporter. It's much harder—but far more impressive, in my opinion—to document the same human drama at home. On your city block. In your house. If you tell me that the spiritual, existential dread of a lonesome woman or man in a middle-class suburb is somehow less interesting or “authentic” than a refugee's woes, I'll tell you that you are in danger of producing shallow cartoons, not original, impactful work. Take the lockdown as a challenge. Dig deeper into the warzone of your own heart.

Take the lockdown as a challenge

© Paul Salopek

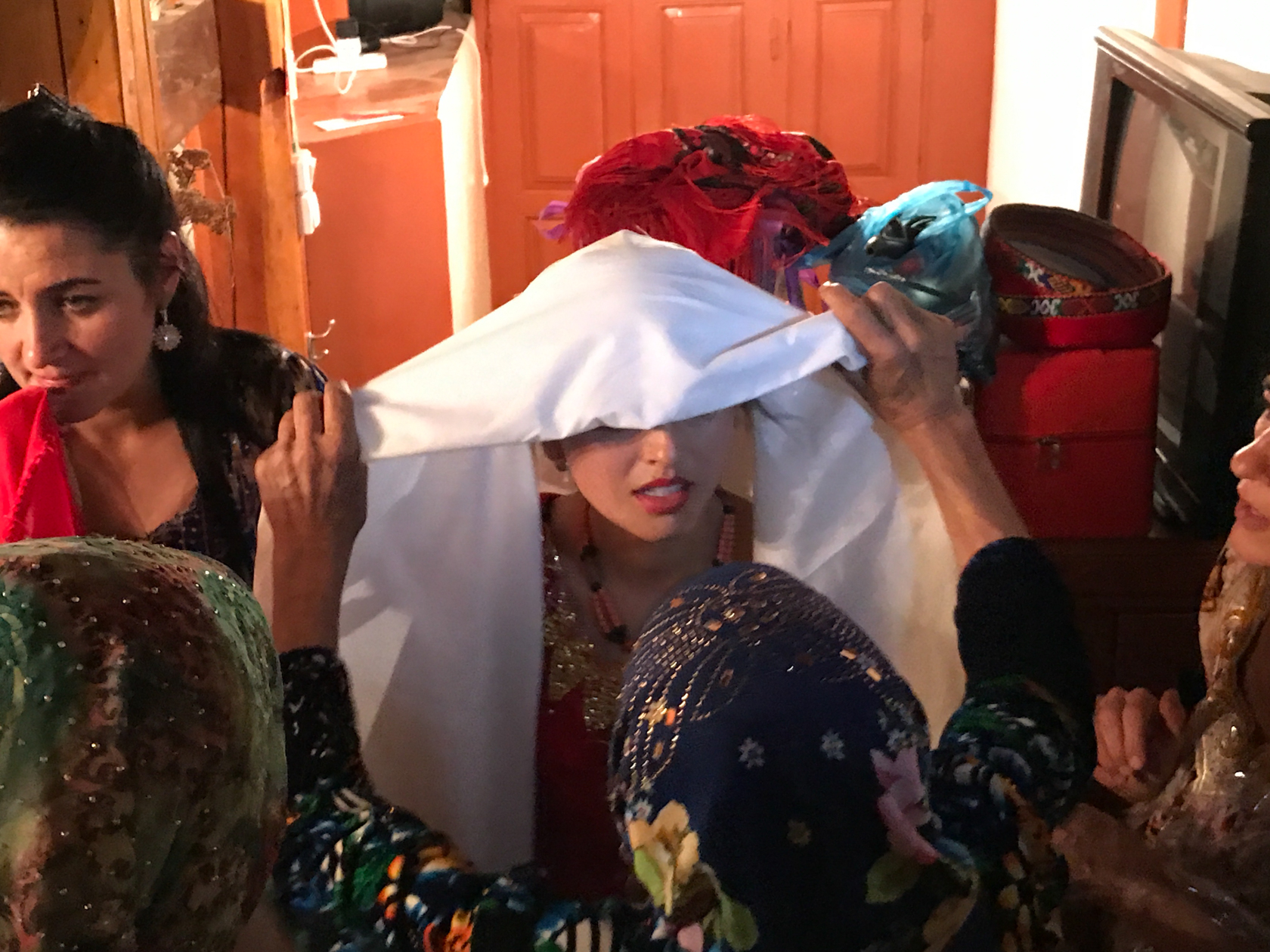

The bride is Safina Shohaydarova, a mountain guide from Khorugh featured in Adamdar/CA's story here

You have been walking for 7 years now, always on the road and far away from home. You know very well what isolation means — in the middle of a steppe or in a remote mountain area. What would be your advice to people struggling to cope with enforced isolation during the quarantine?

Actually, the idea that walking across the world is lonely is pure myth. For better or worse, we live in a crowded world—and I exclude here the rare walked passages of solitariness, such as my 450-kilometer traverse of Mangystau, Kazakhstan's wild western steppes, where I hardly saw a soul. Normally, along my route, I usually greet and interact with dozens of people a day. I hold countless conversations. I stay at people's homes, farms, palaces, caves. I enjoy a different milieu each night at dinner. The past seven years have been, by far, the most social of my entire life. So much so, that at times I must step off the trail to lock myself in a hotel room, simply to have some privacy.

The idea that walking across the world is lonely is pure myth

In that sense, by a chance of timing, the Covid-19 quarantine hasn't imposed a major hardship on me. I had already paused the walk in Myanmar to work on a book when the pandemic broke out. I was already observing a writer's self-isolation—hours in a room alone. I'm not in reporting mode. I am using this hiatus to put it all down on paper. I feel for colleagues who need to be outside right now to work, for practical reasons, in order to pay the bills. I wish I had a solution for that. There are emergency grants to help pandemic “stranded” journalists. The National Geographic Society just launched one. Check it out.

© Paul Salopek

© Paul Salopek

© Paul Salopek

You've walked through the lands of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyz Republic, so you had a chance to observe the environmental situation in the region. What do you think are the main environmental issues and problems that our region is facing?

There are three: Water, water and water. You know better than I the sobering challenges presented by growing population growth, static or shrinking water supply, the impacts of climate change, and the cross-border wrangling over the parsing of the waters of the Amu Darya. Whenever my trailside conversations turned to the limiting factors on human wellbeing in Central Asia, the bedrock environmental factor usually ended up glinting deep down a well or trickling past in a canal—water.

— What are the main environmental issues in Central Asia?

— There are three: Water, water and water.

All of Paul Salopek’s materials related to Out of Eden Walk can be found at the project's website and pages in social media:

Instagram

Facebook

Twitter