During the final battle for Berlin and defeating Hitler’s army, Lieutenant Koshkarbayev became the first army officer to fly the Victory Flag upon the Reichstag in 1945. For many decades one of the main heroic acts that had marked the end of World War II was supressed by the official history.

Brief historical reference:

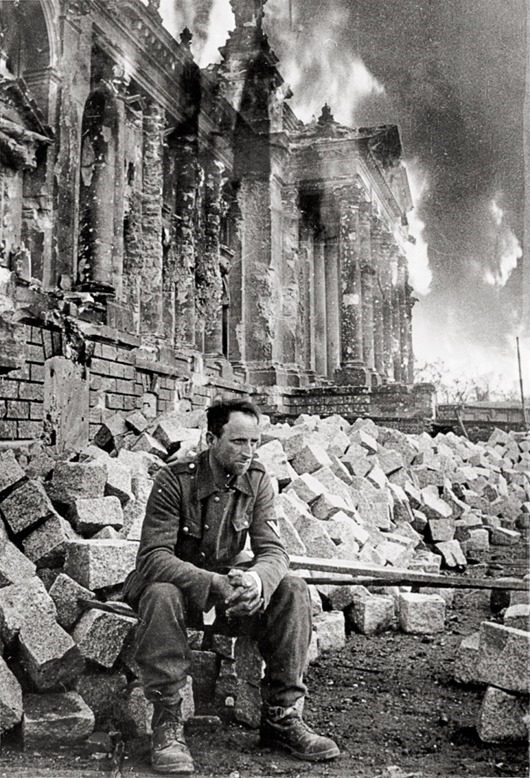

February 27, 1933 — the burning of Reichstag. Hitler and the Nazis used this arson to entrench their power, limit and eliminate freedoms in Germany, start massive repressions and initiate a global war.

September 1, 1939 — Wehrmacht and SS troops crossed the German-Polish border and started their invasion to Poland. Later on the same day Adolf Hitler delivered a speech at the Reichstag. This day became the start of World War II (1939–1945), the deadliest war in human history. The death toll was over 70 million people.

Mid-April 1945 — Soviet troops and divisions of Polish Army started the storming of Berlin. The target was the Reichstag — the main symbol of Nazism and the Third Reich.

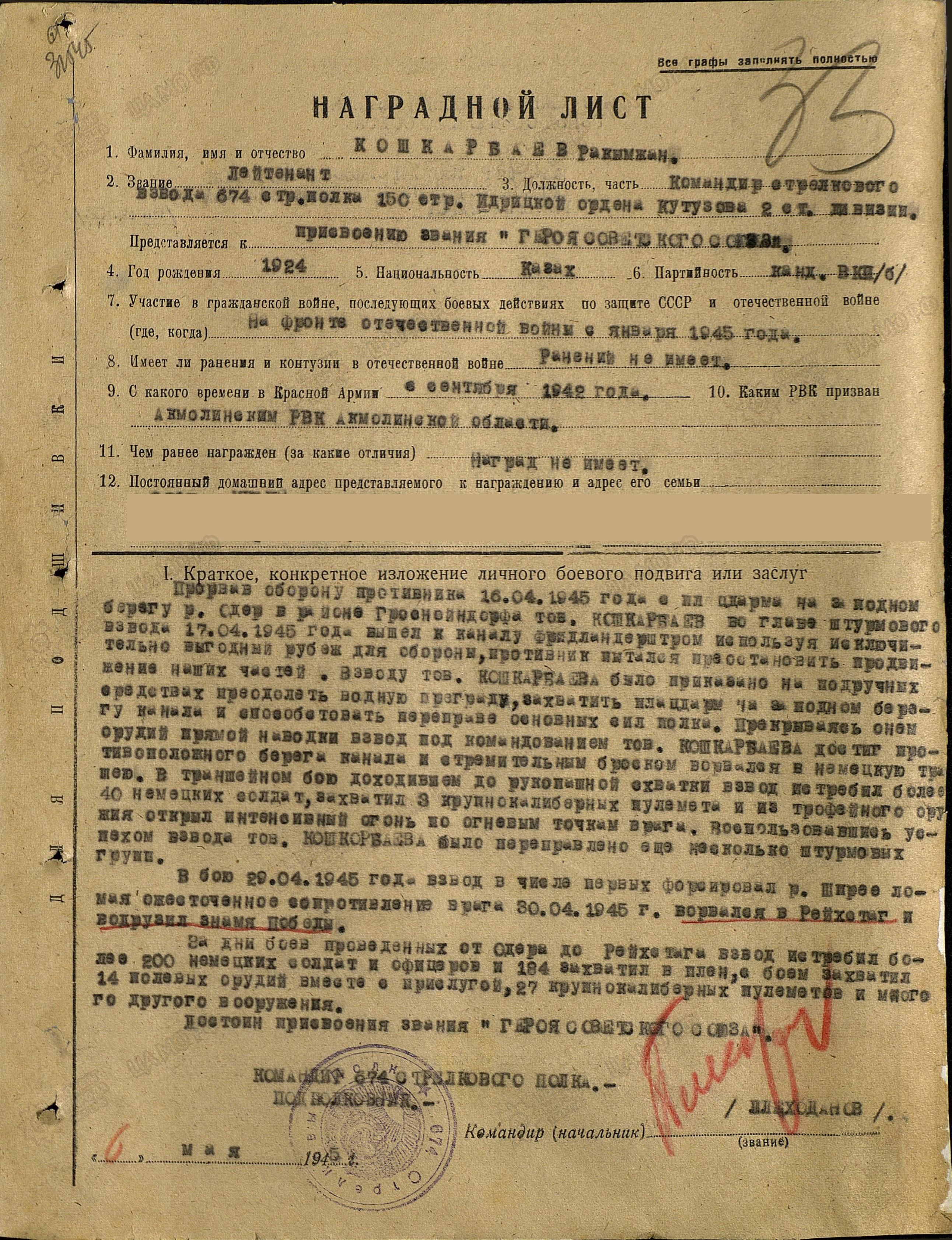

April 30, 1945 2:25 p.m. — the reconnaissance mission commander, Lieutenant Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev, together with Private Grigory Bulatov, under fire from enemy forces, battled through to the Reichstag and planted the flag of their squadron over the main entrance to the building. They became the first soldiers who managed to overcome the hostile fire and raise a flag. That flag became the first banner of victory raised over the Reichstag. The taking of the Reichstag and mounting the flag over it became the symbol of defeating Hitler’s army and the end of the deadliest war in human history.

Approximately at the same time, around 3:00 p.m on April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler, the Fuhrer of the Third Reich, commited suicide in his underground bunker less than a mile away south-east from the Reichstag building.

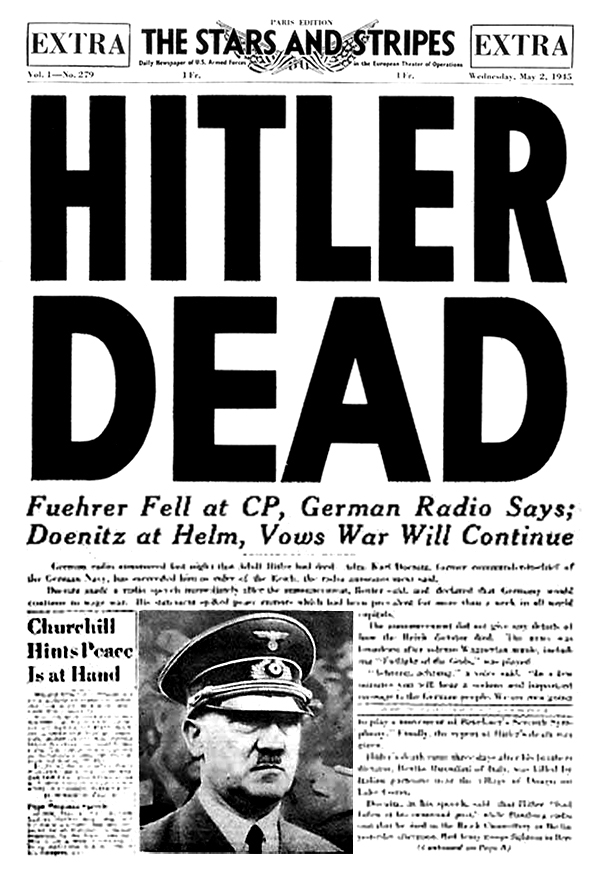

Front page of The Stars and Stripes, American military newspaper (May 1945)

In the Soviet Information Bureau’s report dated April 30, 1945 Yuri Levital announced, “…the front troops, continuing to fight in the central streets of Berlin, seized the building of the German Reichstag and planted the Victory Flag…”

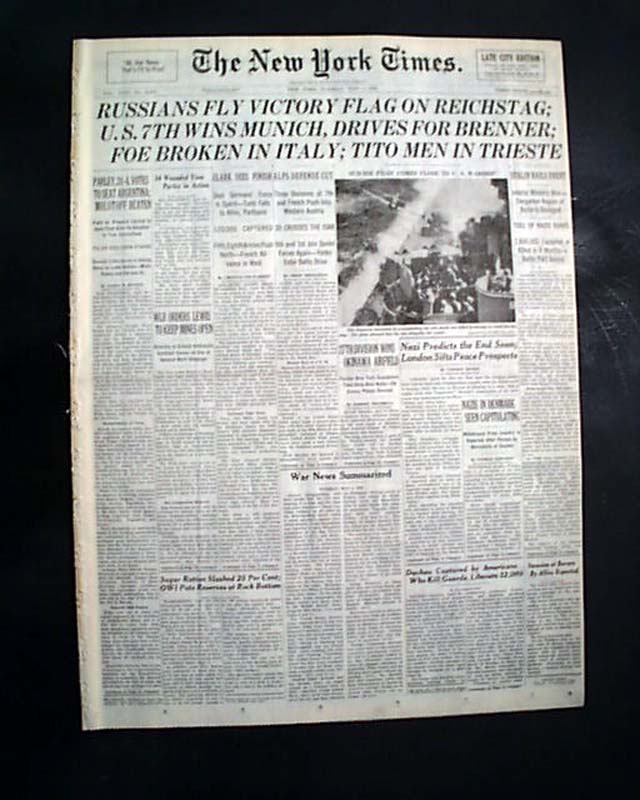

May 1, 1945 — New York Times issued with a headline on the front page: “Russians fly victory flag in Reichstag.”

May 2, 1945 — the Berlin military post capitulated.

May 7, 1945 — Act of Military Surrender signed by the German High Command in Rheims.

On the night of May 8, 1945 the final German Instrument of Surrender was signed in Karlhorst.

In 2004 UN General Assembly declared 8—9 May as a time of remembrance and reconciliation to commemorate victims of World War II.

Lieutenant Koshkarbayev and Private Bulatov’s achievement was not recognized for over 60 years and only in early 2000s, after both soldiers’ decease, it was officially confirmed and documented.

In the battle for the Reichstag

(from Lieutenant Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev’s memories typescript)

April 30, 1945… It was still dark between four and five in the morning. Shells and land mines exploding and tanks roaring all around. Heavy smoke and dust covering the streets. Moving forward was really hard.

Getting inside the building (The Third Reich’s Ministry of Internal Affairs — Å) was impossible because of the enemy’s continuous machine-gun fire. The advance stopped for a while. We lay in wait.

The tankers saved the situation. With a few heavy strikes they clove one of the walls. We used that breach to open fire.

It’s hard to describe what our warriors felt at that moment when we only had taken control of a single room in an eight-floor building — it was just the first stem towards performing the mission…

Before the other troops arrived, we were delivering continuous fire through an open door, lobbing grenades to the enemy through windows and staircase doors…

There was a battle for every room, for every floor

Despite the grim resistance of Hitler’s soldiers, as soon as the rest of the troops arrived, our onrush strengthened. There was a battle for every room, for every floor. In some places hand-to-hand fights ensued. Gradually the battle moved towards the second floor.

The dawn was breaking. The area taken over by us significantly expanded. We needed a lot of ammunition, especially grenades, to clear the entire building of the Nazis. As we would always do in such situations, to fight the enemy we used their own munitions that were stored abundantly here in the same building.

By noon some of the troops reached the fourth floor, and my platoon was among them.

I would like to mention the names of my platoon’s warriors who particularly distinguished themselves in that battle: Senior Sergeant Nikolay Goncharov awarded the Order of the Red Banner (posthumously), Private Grichko awarded the Order of the Red Star. Bravery and gallantry they demonstrated in the battle set the example for everyone.

During the battle I was told that the battalion commander called me. I had left Nikolay Goncharov (who died by the end of the day) in charge, went down to the first floor to the commander and reported on my arrival. Along with the commander there were Vasilchenko and the batallion party organizer, as well as reconnoiters of our unit: Provotorov, Lysenko, Oreshko, Pochkovsky, Brekhonetsky, Sorokin and Grigory Bulatov. They huddled against both sides of the wall because of the non-stop machine-gun firing coming through the broken window from the buildings across the street.

Then the commander said to me, “The moment the hostile fire pauses, quickly look at the square outside the window. That big grey building with a dome you will see there — that is the Reichstag.” After a pause, he continued, “At the moment, our battalion is the closest one to the Reichstag. So the aim is as follows: make the way to it as soon as possible and mount the red flag. Upon the recommendation of comrade Vasilchenko, I called on You to accomplish this task. And I must warn you that this is not a command. Think it over and decide yourself. While gaining the ground you will be backed up by fire of our reconnaissance men who arrived from the headquarters for this purpose.”

When the commander said that I had been called upon Vasilchenko’s recommendation, I looked up at that aged silver-haired man, all covered with dust, with a rifle hanging on his neck. He was looking at me and waiting for me to respond…

I immediately started to get ready to sally… I only took a rifle, a handgun and three hand grenades. Holding the flag in my left hand, I reported to commander that I was ready to accomplish the task. Davydov shook my hand and wished me luck. Political commissar comrade Vasilchenko approached, he gave me a hug and kissed, “I wish you luck, Rakhim. See you soon…”

Reconnoiters were ready to take off, too. We waited until the fire paused, I jumped out of the window and lay down in a shell hole. There was only Bulatov next to me. “Comrade lieutenant,” he said, “the other reconnoiters could not jump. Fire. We’re lucky — we got through.”

I told Bulatov that we were going to creep, one behind another. Machine guns were heavily firing from each side, so we could not even raise our heads. We were slowly creeping, right after each other.

When we creeped out of the shell hole, the only cover ahead were the iron beams stowed nearby. Upon reaching them, we got our act together and quickly got the lay of the land. The next cover could be the transformer box 40-50 meters away from us.

The square was too exposed — nowhere to hide. Just that box. The journey to the box was hard and exhausting. Just imagine: landmines exploding everywhere, bullets buzzing, face almost touching the ground, can’t even move my head — otherwise it would be noticed. We were moving so slowly that one could hardly tell we were alive. Finally, we reached the box. Our clothes were soaked with sweat. The box was wood-framed and all holed through with a hail of bullets. It was too dangerous to stay there any longer. Besides, we could easily come under fire of our own troops, because no one knew about us, except our battalion. This forced me to make a quick decision. A minute to inspect the field: there was a broken iron bridge between the Reichstag and us, about a hundred meters away. But again, there was a flat exposed square leading that way.

To the right from the Reichstag there was a park. That was Tiergarten, from which Germans were bringing their machine-gun fire.

Second half of the day. Our spotter planes started to appear above us more often. Just after they left, a massive artillery barage rained down on the park and the Reichstag. Heavy gunfire and explosions raised plumes of black smoke, fire and dust over the square.

We could not wait any longer. We took a risk. Sprang to our feet, we blast towards the bridge as fast as we could. It was really interesting to recall afterwards that while running, we took each other by hand. We noticed that only the moment we reached the bridge and fell right into water.

The channel was shallow. Despite the bullets whistling all around, for the first time on that day, we looked into each other’s eyes and smiled unintentionally.

I took out the red flag, unfolded it and with an ink pencil wrote the number of our unit in the corner — 674, and our surnames: Bulatov, Koshkarbayev

Because of the danger, we had to relocate to the opposite side of the channel. Now we are around three hundred meters from the Reichstag… The fire is getting more intensive along the shores on both sides. Forging ahead is impossible. 20-30 minutes passed. We’re still not moving. I took out the red flag, unfolded it and with an ink pencil wrote the number of our unit in the corner — 674, and our surnames: Bulatov, Koshkarbayev. Bulatov watched me write and then said, “It’s good that you wrote that, comrade Lieutenant. We might get killed and no one will even know who we were and we were from.” “Go, run!”, I said to him.

At that moment we didn’t see or hear anything, we were just running ahead. The first steps of the front entrance to the Reichstag. We reached the wall, huddled up to one another and held our breath for a moment. After a minute-long silence I remembered that we need to plant a flag on a well visible place. We were so happy that could not even think of a dome. I helped Bulatov sit on my shoulder and lifted him to the railings near the window. “Grisha,” I said, “mount the flag as high as possible.”

He replied, “There’s nothing to attach it to. Hold me a little longer — I will take a brick from the window.”

A minute later Bulatov exhaled huskily, “Done! I PUT IT.”

Ever since then April 30 is a second birthday for me. Every year on this day I have a special feeling of joy. Those hours of struggle and happiness are unforgettable.

Afterword

After planting the Victory flag reconnoiters Lieutenant Koshkarbayev and Private Bulatov continued to take part in the battle for the Reichstag. Flying the first Victory flag over the Reichstag had a powerful psychological and symbolic impact on the battle. Following Koshkarbayev and Bulatov, several attack teams of the regiment 674 burst through to the Reichstag and after the fierce fighting the building’s military post capitulated. Lieutenant Koshkarbayev got injured in that battle.

Koshkarbayev and Bulatov’s heroic act had been documented in the division’s military records, a number of battle-field and Soviet papers wrote about it in May 1945. For the act of bravery performed in Berlin the regiment command recommended Koshkarbayev and Bulatov to the highest military award — titles of Heroes of the Soviet Union. But, due to ideological reasons, Koshkarbayev and Bulatov’s act was not officially acknowledged by the official Soviet government. One of the possible reasons could be the fact that Koshkarbayev was a son of “an enemy of the people” who was repressed in 1930s. The “official” victory flag-bearers were the Red Army soldiers Yegorov and Kantaria who planted a different flag a few hours after Koshkarbayev and Bulatov, after the main battle for the Reichstag.

Grigory Bulatov’s after-war fate was tragic: he repeatedly tried to confirm the fact of his heroic deed in the battle for Berlin, in vain. He was dubbed Grishka-Reichstag for that. Bulatov served two terms in prison. Until the end of his live veteran Bulatov kept in touch with Koshkarbayev. In 1973, 42-year-old Bulatov commited suicide.

Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev had been demobilized after the war and later started a life in Alma-Ata. He was engaged in the construction of one of the main symbols of the city — the Alma-Ata hotel and became its manager.

In civil life Koshkarbayev wrote two books — “The Victory Flag” and “The Storm”. After the war Koshkarbayev found his father, who had been repressed in the 1930s and later released from GULAG. In Alma-Ata Koshkarbayev met another war hero, colonel of the guards and writer Baurzhan Momyshuly and remained friends with him until the end of his life.

By virtue of Momuyshuly’s awareness-building work, thousands of people found out about Koshkarbayev and Bulatov’s achievement during the Soviet times, and in counter-culture they were perceived as the true Victory-bearers.

In 1999 in independent Kazakhstan Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev was awarded the highest degree of distinction — Khalyk Kakharmany (National Hero — Å), posthumously.

In early 2000s, due to the historian Bulat Asanov’s research work, reconnoiters Koshkarbayev and Bulatov’s heroic act was officially confirmed with the documents from the Institute of Military History of Russian Ministry of Defense.

Until the end of his life, Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev treated April 30 — the day the Victory flag war raised over the Reichstag — as his second birthday.

The Adamdar.CA team would like to express their gratitude to Aliya Koshkarbayeva and Dauren Koshkarbayev for the help in preparing this article.

Document and image credits: personal and family archives of Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev, state and military archives and open online sources.