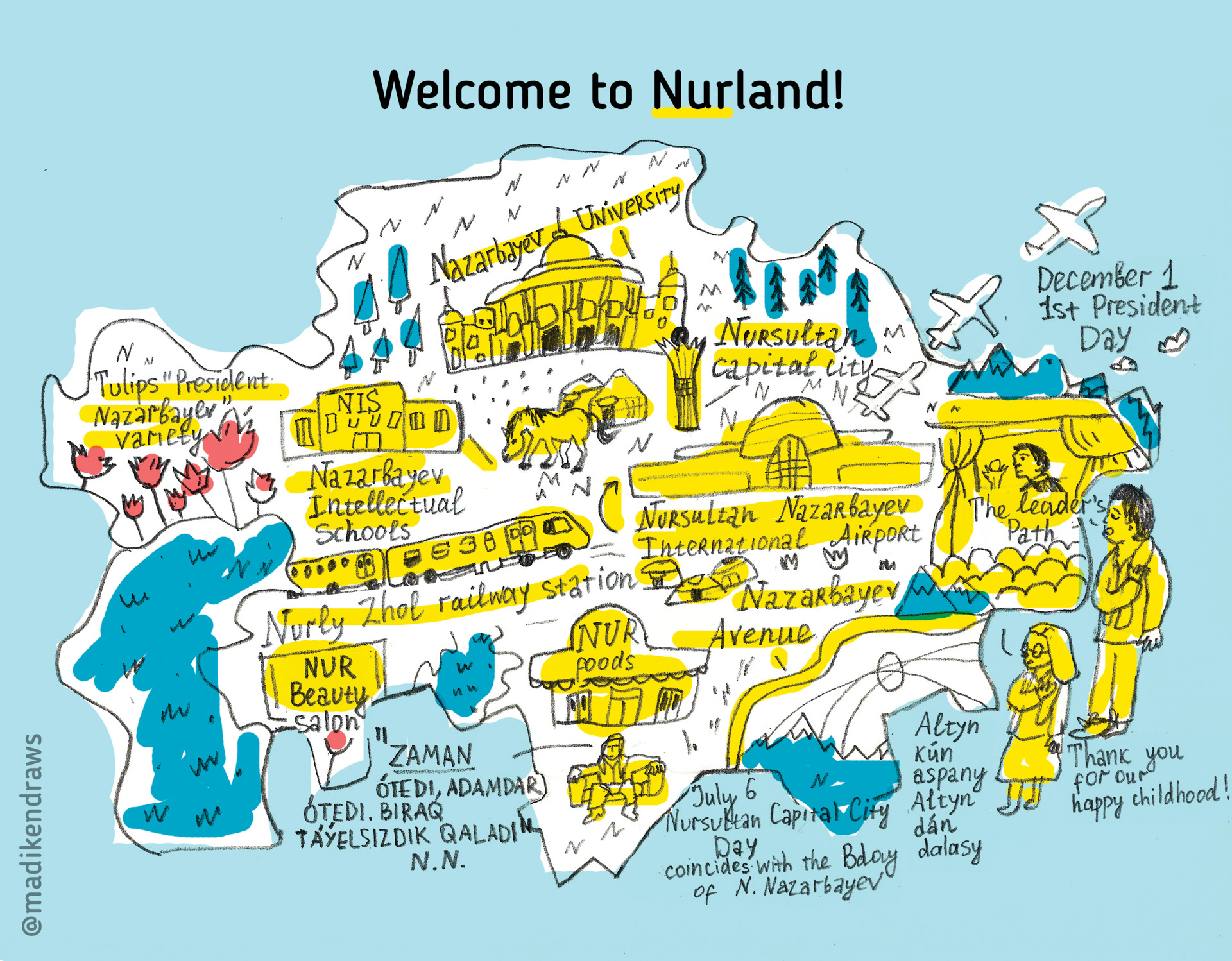

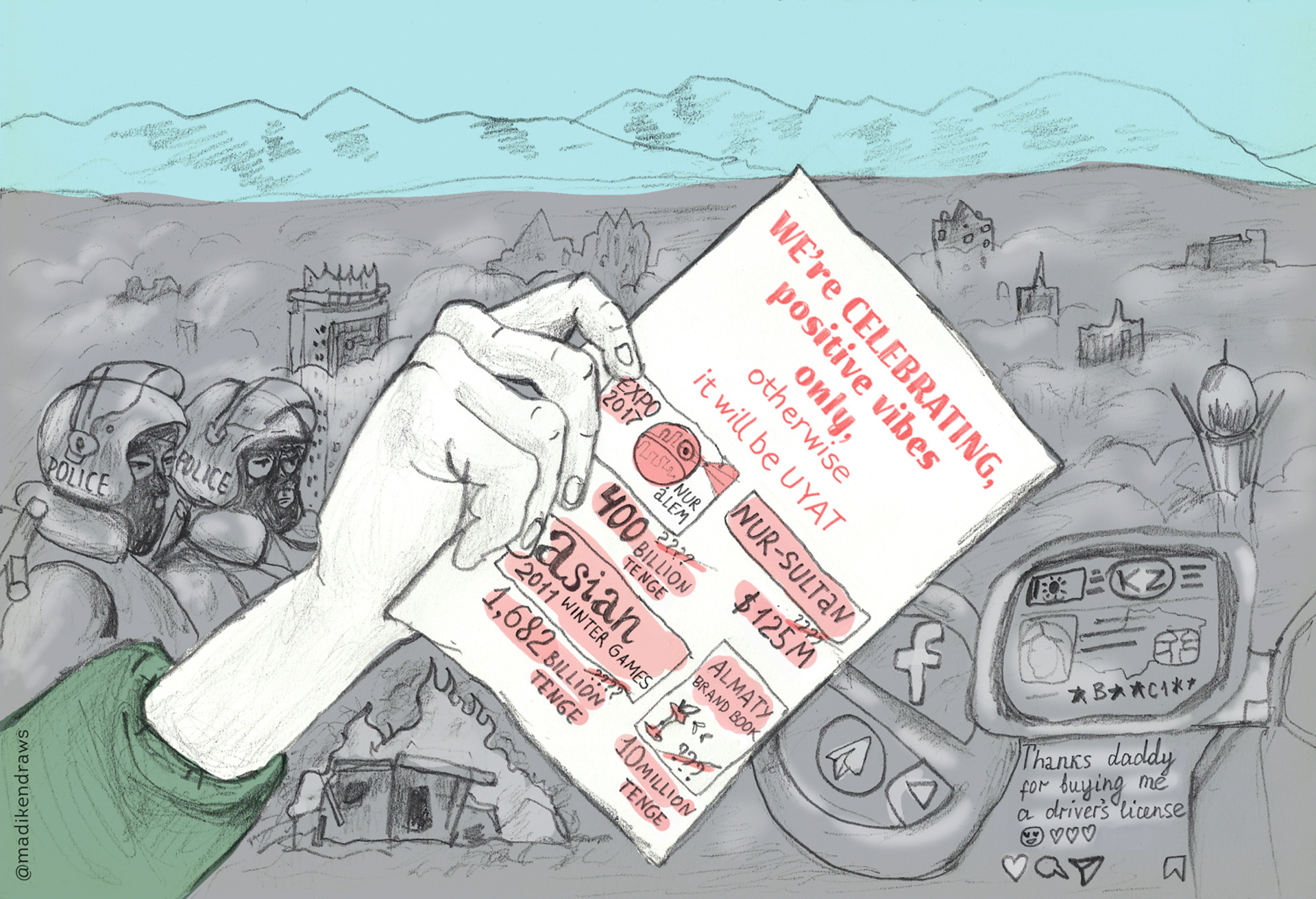

Madina Zholdybekova (@madikendraws) is an artist and illustrator from Kazakhstan. During the recent events associated with Kazakhstan’s political changes, her drawings reflect not only the cognizant artist’s deep, insightful point of view, but also the sentiments of many Kazakhstanis about the situation in their country. Madina’s work has taken social media by storm, becoming a vivid visual symbol of the events of March 2019 in Kazakhstan.

INDEPENDENCE

My name is Madina Zholdybekova. I was born in 1991 in Zhezqazghan, Kazakhstan. I remember that in elementary school, those who were born in 1991 were given gifts because we were the same age as Independence. These gifts usually were books and jewelry boxes. Those who were born on the 16th of December were the luckiest of all — their gifts were large encyclopedias and trips to cafés. I was born on May 12; in other words, a bit too early to receive those extra-special gifts, but just in time to say that I’ve lived a bit in the Soviet Union.

When I was three, my family moved to Tekeli, and then back to Zhezqazghan. At the age of eighteen, I moved with my parents to Almaty. Now I live in Istanbul. There you have it: my nomadic life.

Even though I spent most of my childhood in Zhezqazghan, it was Tekeli that left the greatest impression on me. With its spring water, clean air, and fresh fruits and vegetables grown right in our yard, this city at the foot of the mountains framed the happiest time of my childhood. And now, when I think about Kazakhstan, images from Tekeli fill my head: verdant greens, effervescent streams. And the apples there are very tasty.

As a child I graduated from art school, but I was always fond of the hard sciences, and they came to me easily. Moreover, I grew up in a typical patriarchal family and never went against the grain. Technical specialties were held in high esteem at that time. Therefore, like a good, serious-minded girl, I entered KBTU (Kazakh-British Technical University), specializing in IT. I studied there for four years. At the same time, I drew, taught myself graphics programs, and worked in the laboratory of computer graphics of KBTU. When all was said and done, I’d graduated from the university, earned a diploma for my parents, and went off to work as an illustrator at Rocket Firm. It was then that I realized – illustration is my calling. At Rocket Firm, I found the opportunity to explore various trajectories; besides graphic design and illustration, we carried out many creative projects, designing everything from comic books to interactive iPad games.

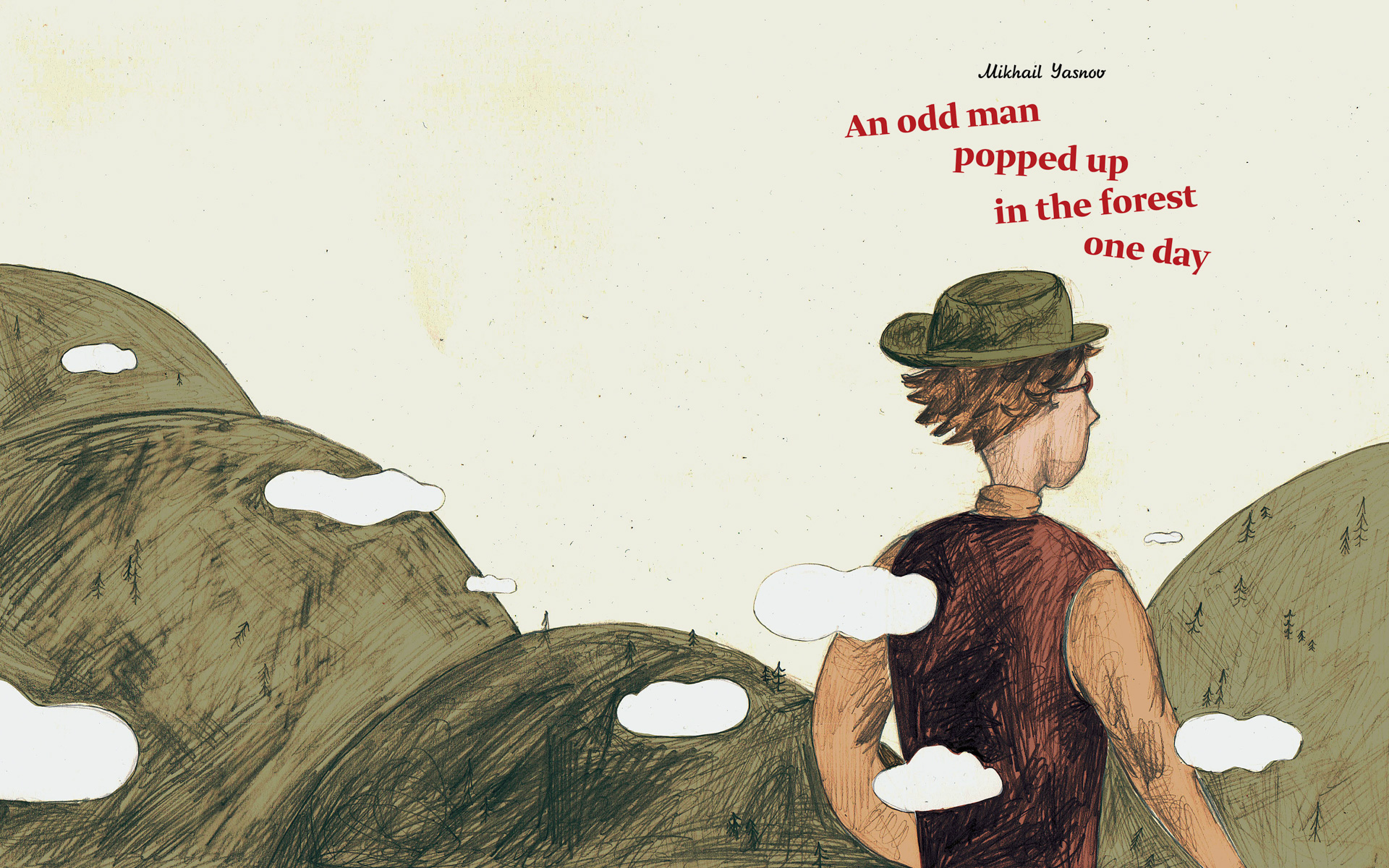

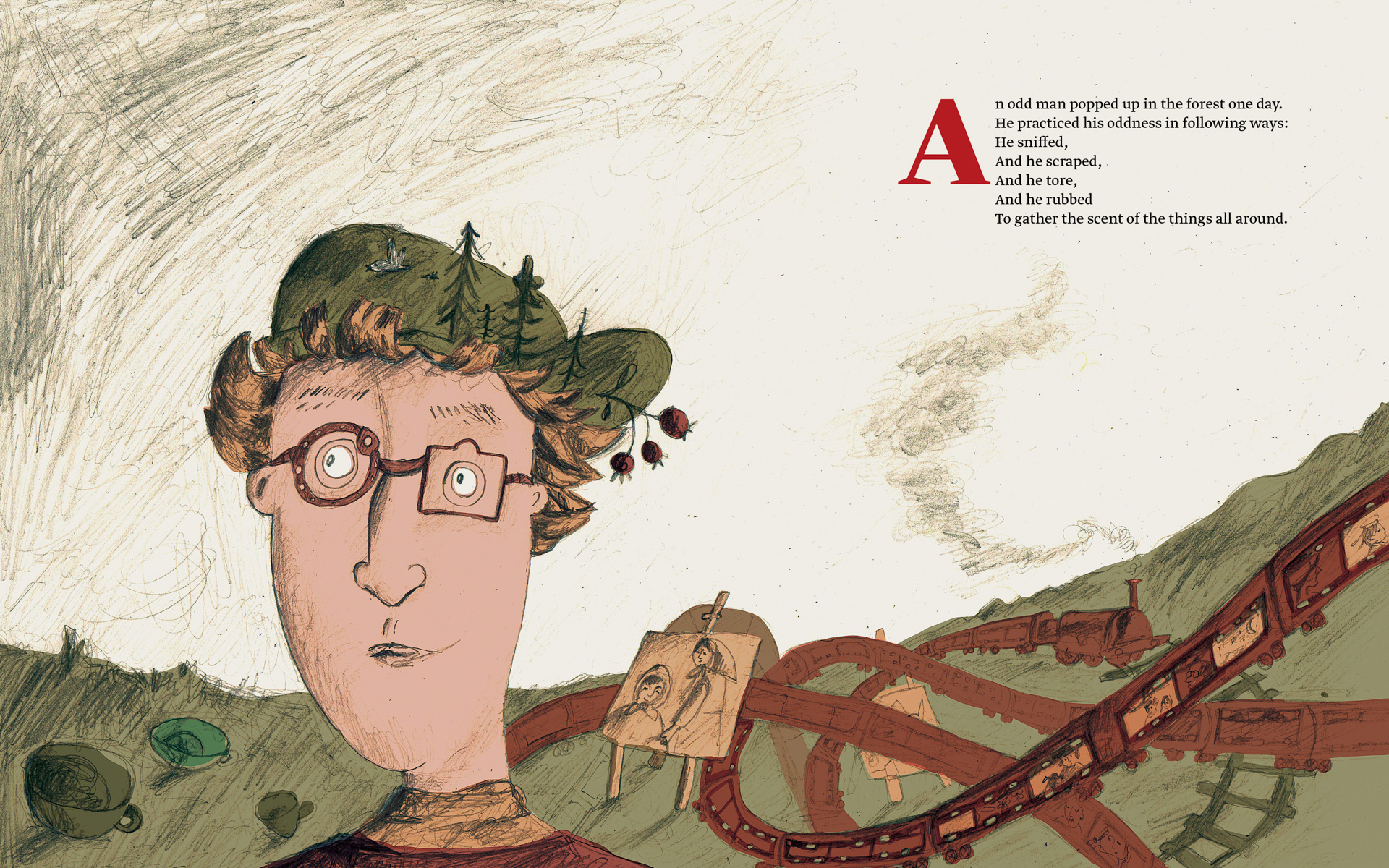

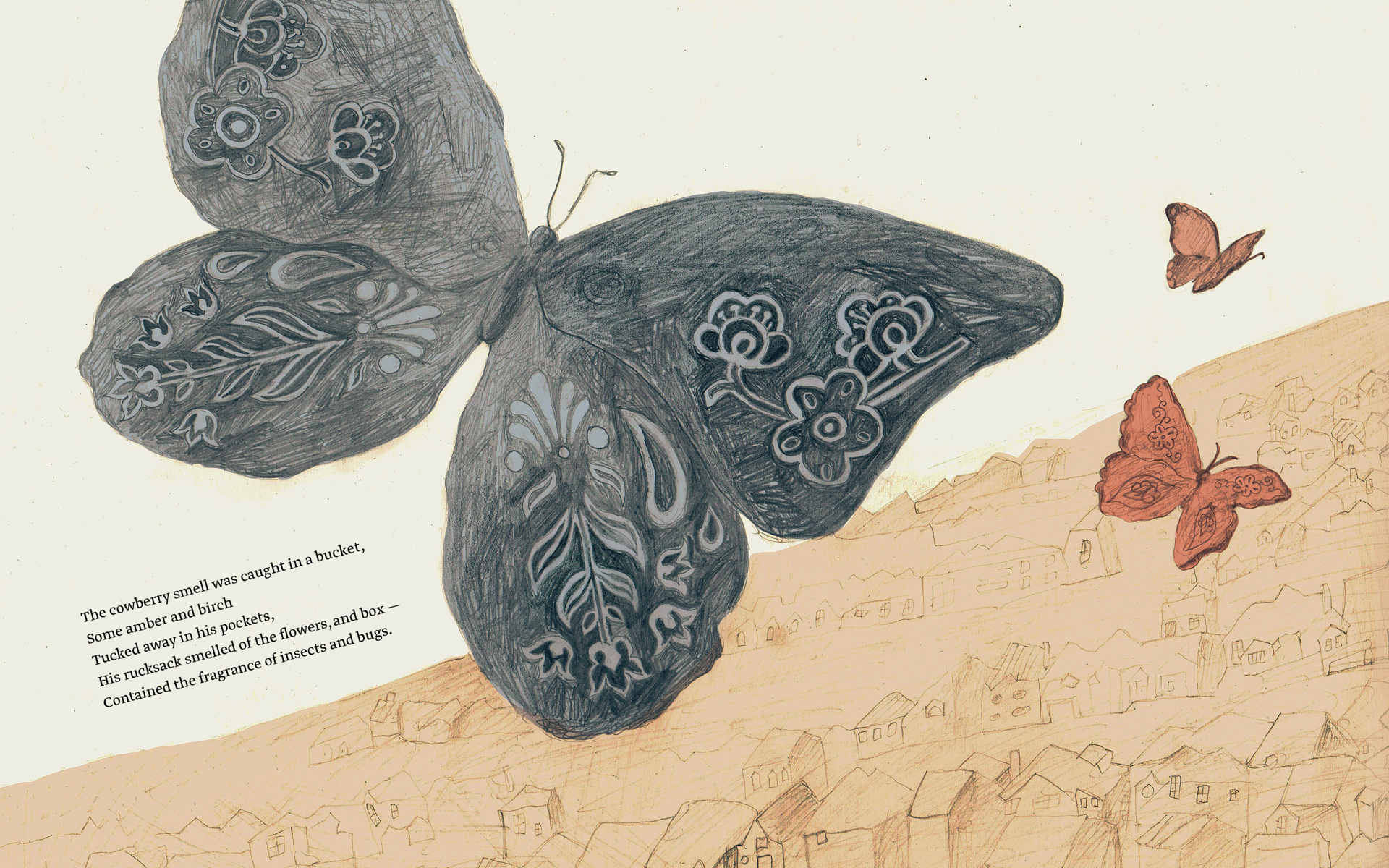

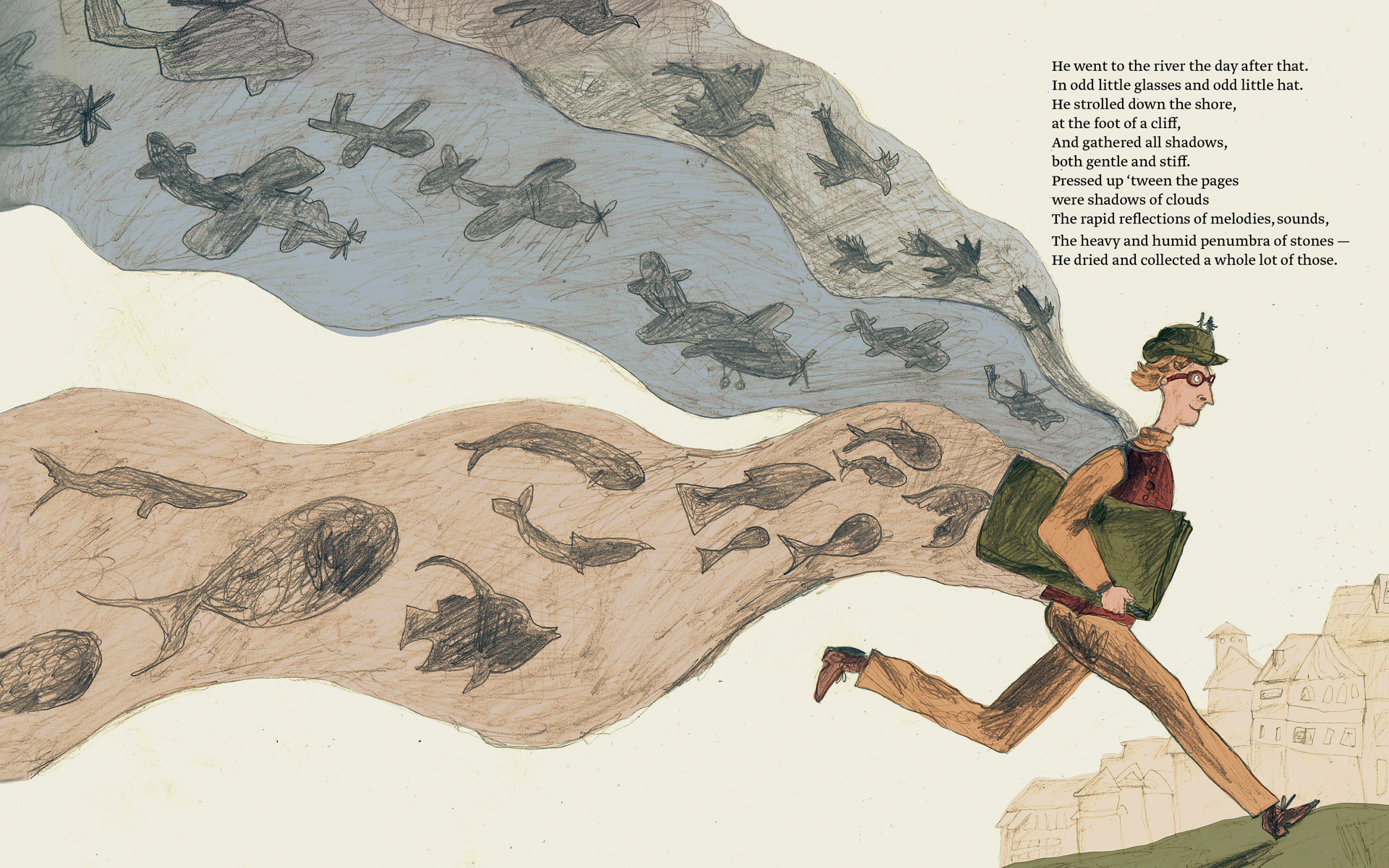

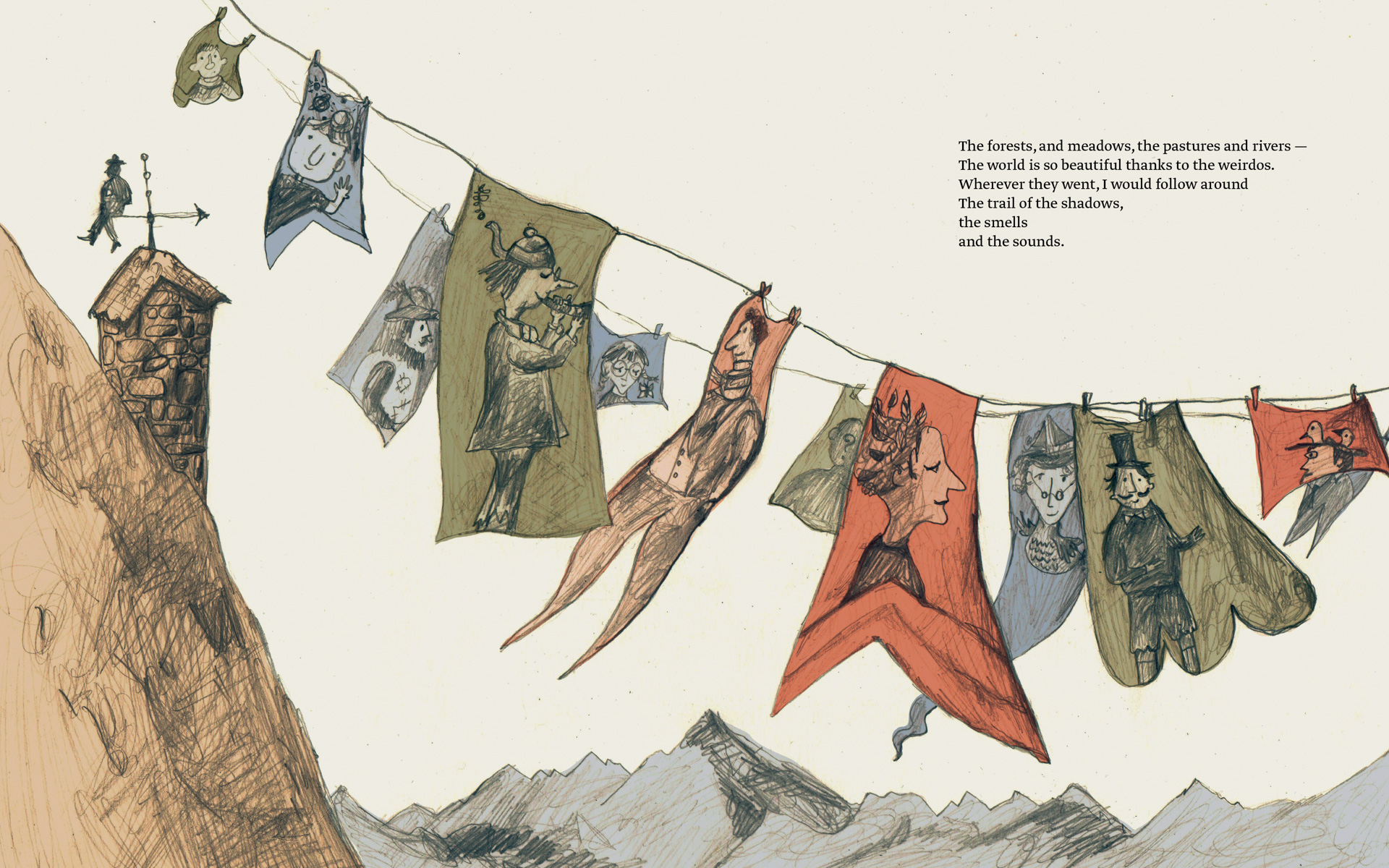

As my time at Rocket Firm came to an end, I decided to try out children's illustration, studying for half a year at the Moscow School of Illustration and Painting. During my studies, I illustrated a book called “An odd man popped up in the forest one day.” I was proud of my work on this book, and it turned out well, but it ended up on the melancholic side, more for adults than for children.

To illustrate children’s books, you don’t descend to their level. On the contrary, you must rise.

Thanks to this experience, I realized that in order to illustrate children’s books, you don’t descend to their level. On the contrary, you must rise. Astrid Lindgren dreamed up Pippi Longstocking at 38 years old, and Nikolai Nosov invented his character “Dunno” at 50 years old. Obviously, you need to have lived some life in order to learn to feel metaphors at the level of children. And it takes special skill to not spell everything out so literally, so some room remains to write or draw a little something between the lines.

Upon completion of my formal education, I joined the team of OYLA, a new popular-science magazine, and worked there as an illustrator for about three years.

I love absurdism in art. It helps relate to life with a smile, especially when you start getting carried away with being a serious adult. I was born in the most ideal place to feel absurdism on myself and to be inspired by it.

You never know where the line will lead

I like primitive art the most, although many people don’t agree with me. Usually, when my relatives or friends look at what I draw, they say: "Well, I can do that, too." I don’t like to spend too much time on my illustrations. I hate hyperrealism. Quick solutions are more appealing to me, like mixed media. For example, many of my recent drawings are pencil or gouache on paper, filled with color, and then overlaid with text. But these kinds of illustrations are all non-commercial. Commercial graphics love brighter colors and volume.

Now I’m on maternity leave, and this is the perfect time to engage in self-expression. I am my own art director: what I want to draw, I draw.

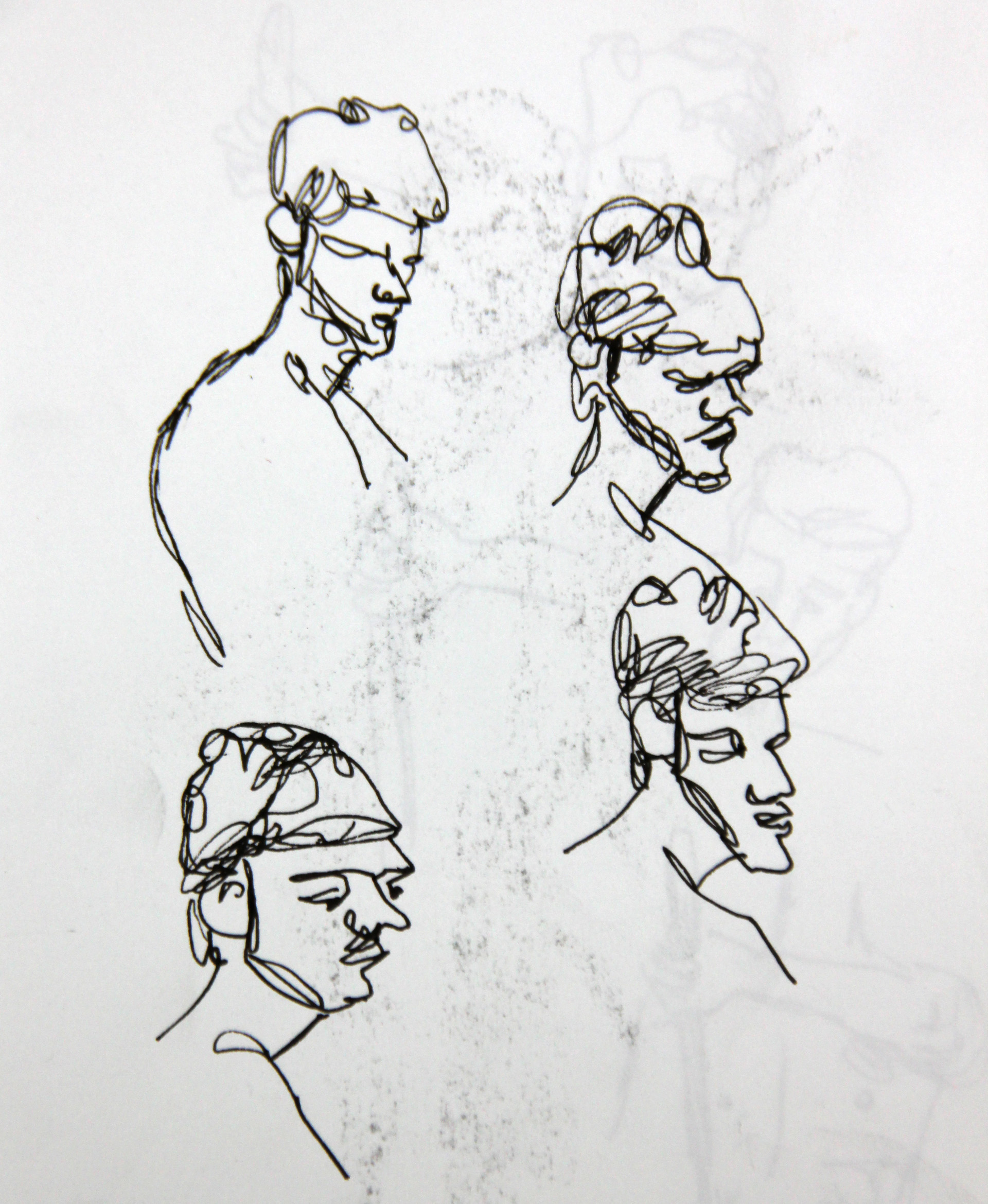

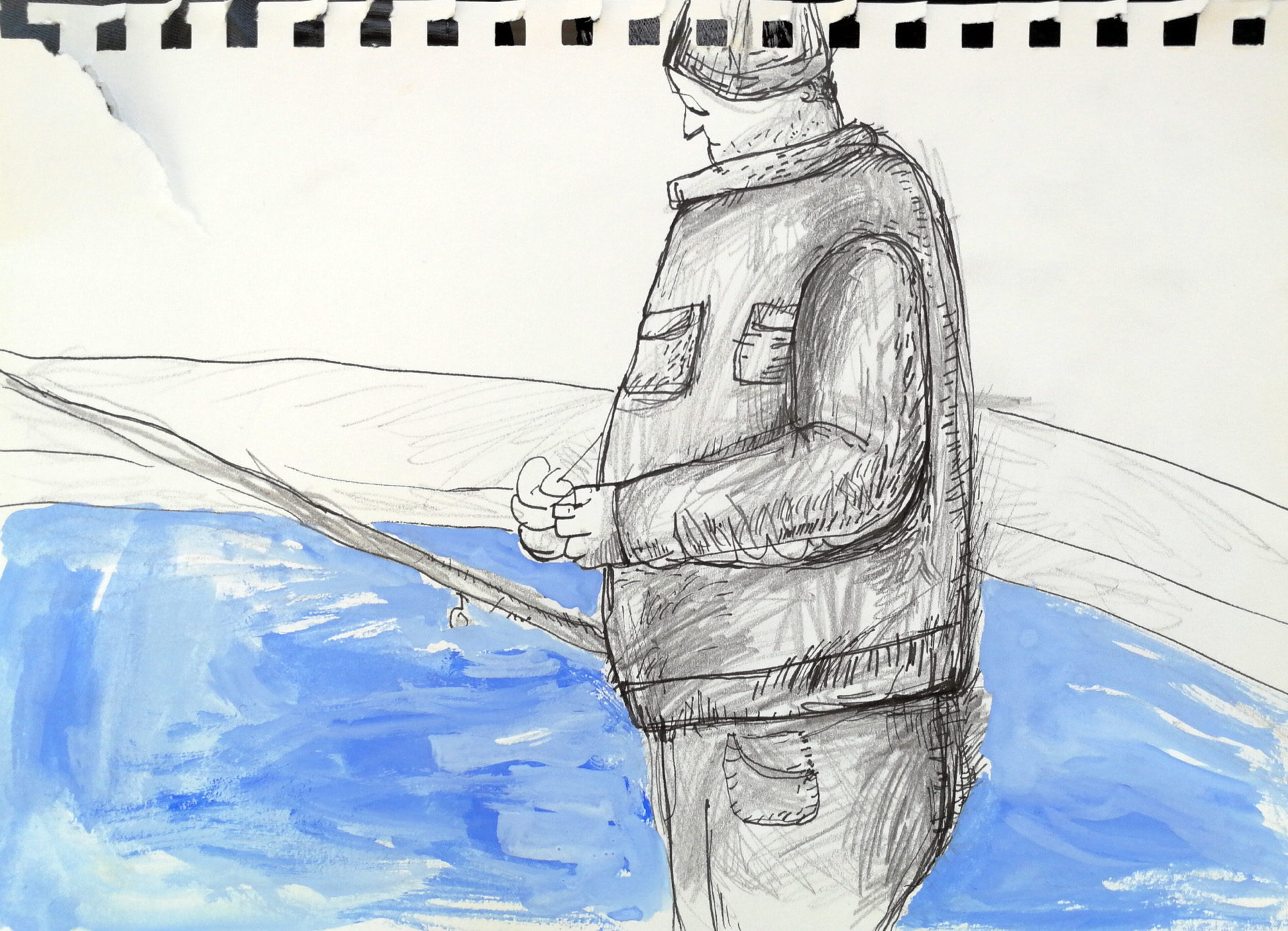

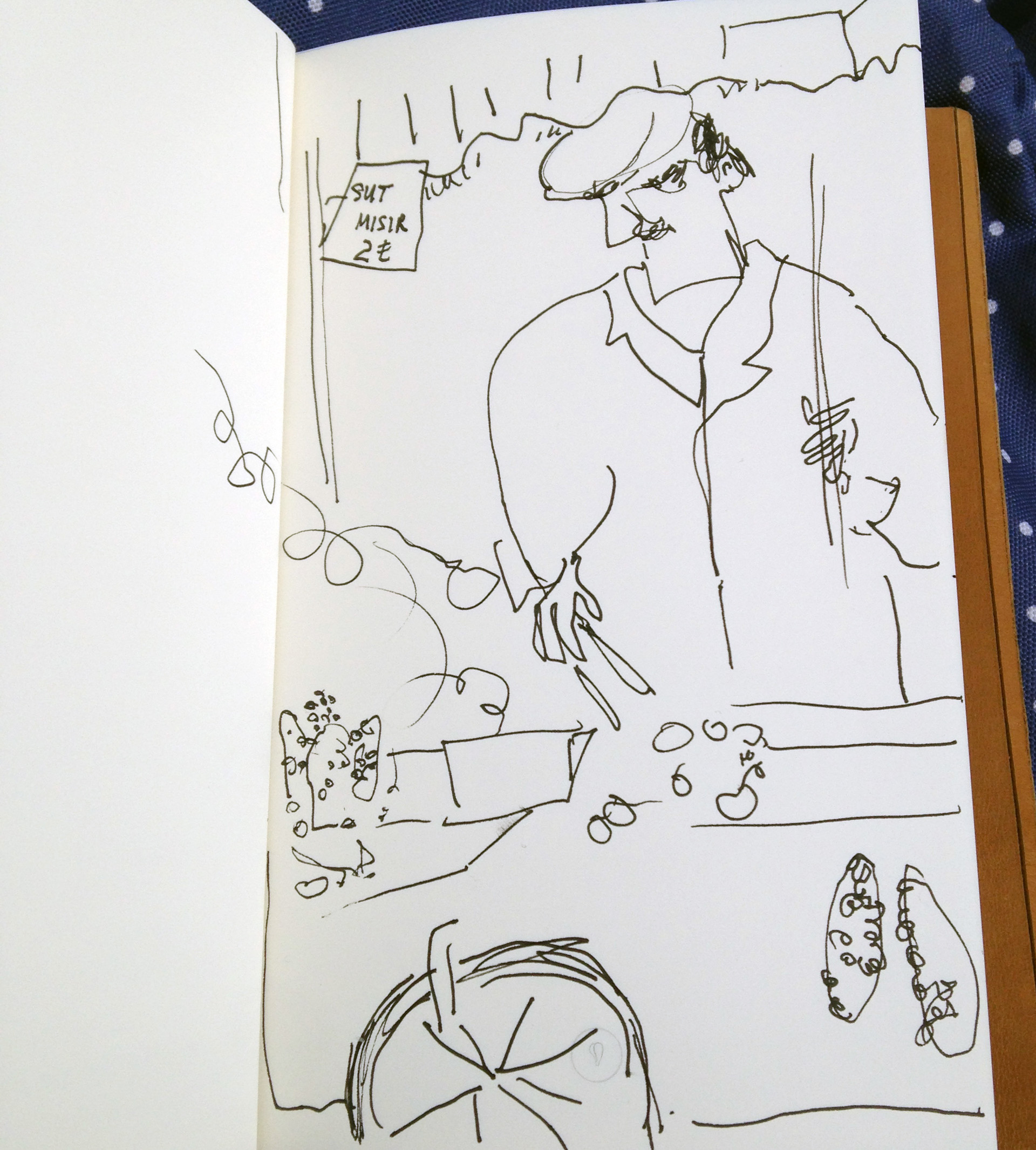

My sketches are a portal to memories. I document and get acquainted with my surrounding reality through sketches, collecting impressions on paper. Adventure spying through drawing: you never know where the line will lead.

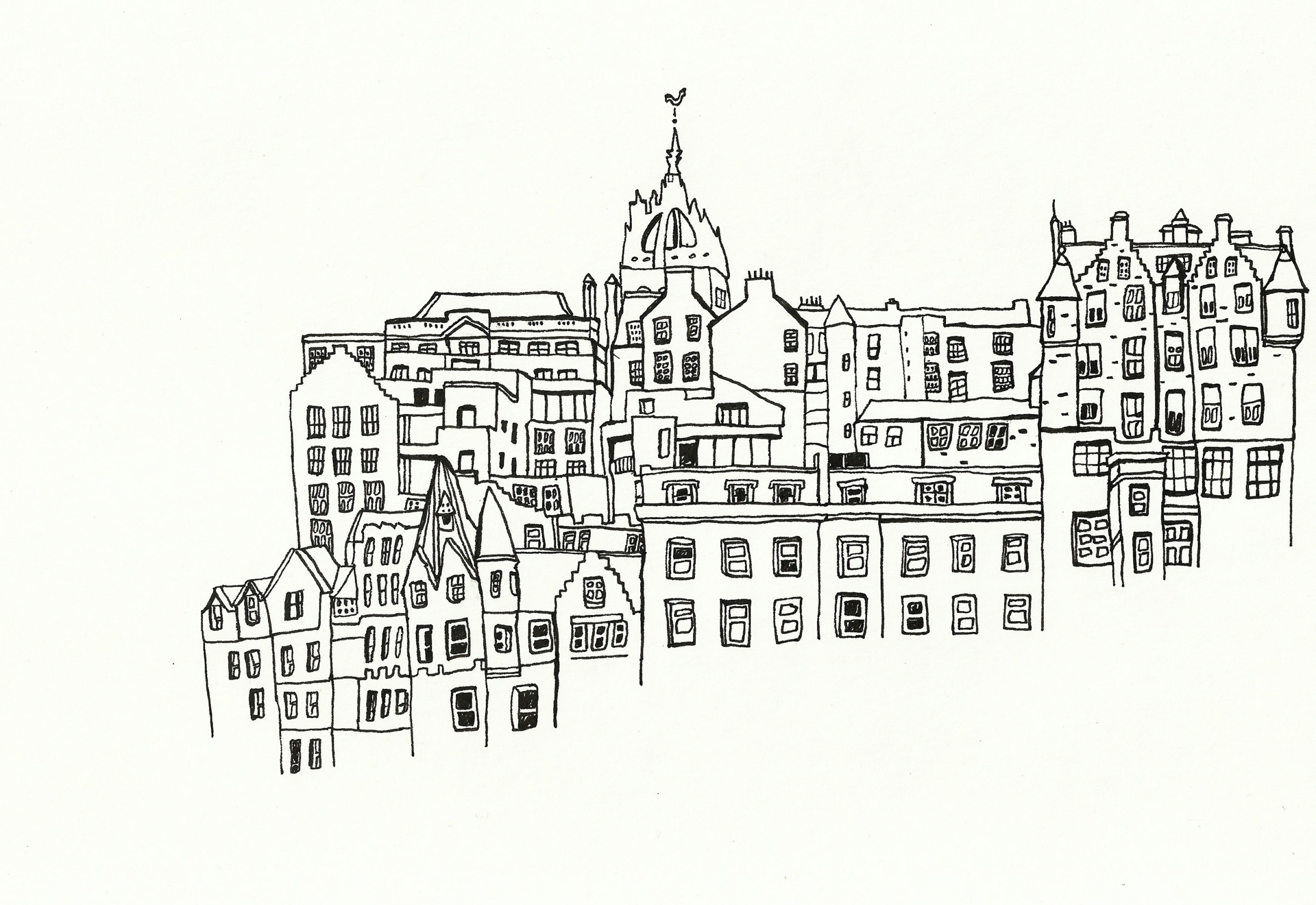

TURKEY

I’ve been living in Turkey for a year and a half. Istanbul is a very resourceful and generous city, an ideal place for spotting interesting characters to sketch. I’m absolutely crazy about the fishermen and tea makers here. There are no artists’ models more grateful than the fishermen on the Bosphorus.

Turkey is not just about all-inclusive resorts

Many in Turkey do not know that Kazakhstan is their ancestral home, though some understand that we were brothers before, and they accordingly say: kardeş. But I noticed that our people have quite a distorted image about Turkey.

Turkey is not just about all-inclusive resorts, Antalya, Tarkan. Turkey is the natural beauty of the cities of Kas and Rize, the photos of Ara Guler, the books of Sabahattin Ali, the music of Fazıl Say.

If someone told me five years ago how closely I’d bind my life to Turkey, my culturally-illiterate past self would not have believed it.

In Turkey, people’s souls are open wide. They are very affectionate. People generously adore their children, especially men. This could not but affect the self-esteem and self-confidence of a person. We, of course, also love our kids, but you’ll find a much smaller proportion of our men lovingly caressing their children. An entire generation has grown up in our country with living fathers, but brought up only by their mothers.

MOTHERHOOD

When my baby was born, I was overcome by a tangible feeling that someone had inflated me. Why does nobody talk about the complications of child-rearing? Everyone posts beautiful photos, but nobody shares the difficulties, as if it's shameful to write about them. It seems to me that people should also write about what is happening "behind the scenes" of happy motherhood.

I noticed that in our society, in general, there is a very strange attitude towards mothers. A new mother needs to be supported and praised, but we consider it necessary to give a lot of advice, causing a mother to doubt the correctness of her actions. There’s a lot of criticism and intimidation. You are set up against your own child. "He manipulates you, Madina. Do not take him into your arms, or else he’ll grow accustomed to it." But a two-month-old baby is too immature to manipulate people – he’s first got to understand the cause and effect of his actions. For this reason, my most recent illustrations have been, for me, exercises in psychological processes: to learn to express anger in an eco-friendly way, and to be able to say no. This has always been difficult for me; I’ve always suppressed this ability.

My anger has become a resource for my recent publications

On March 20, I felt rock bottom. Of course, this is all theater. But this is bad theater, these are bad actors, and this is such a clumsy production! The authorities of our country do not take into account the opinions of our people, and for me this is insulting. These feelings gradually accumulated in me, and motherhood only aggravated them. Children often upset you, like when you spent two hours tucking them into bed only for them to sleep for half an hour. Perhaps nature has designed children so cute and attractive in order to protect them. When you cannot direct your anger at your child, it builds up, eventually expressing itself in the form of anxiety. Mothers are anxious creatures. But a part of the anger still remains.

This anger has become a resource for my recent publications. I used to be apolitical; it seemed to me that I could not change anything. Now, of course, I know that I won’t change the world with these pictures, but this is my only way to voice my dissent, to mark the limits of my freedom, to say that I do not like what is happening.

Relatives worry about me, but I'm not frightened. Nothing I do is illegal. I’m just expressing my position. And anyway, how much can one be afraid?

Unfortunately, many people are leaving Kazakhstan. About a third of my circle has left: to Canada, Europe, and very many to Silicon Valley. Yet another third are packing their suitcases. Tired of speaking into emptiness and working futilely, they leave because they have no hope left.

Sometimes it seems that the people in power simply do not know about our existence. Our lives have no overlap with theirs, as if we live in parallel worlds. It’s terrible.

Throughout the world, young people have always been a politically active, enlightened part of society, but we mostly have trolls, nihilists, and people who are easily manipulated via exploitations of their vulnerabilities: money, or threats to be expelled from their universities.

I look around and I understand that we’re still in a comfort zone, as if the state needs to clamp down even further, but until they do, we can all keep enduring. Opportunities remain: to buy things, to travel once a year, to go out to brunch. Everything is fine; people are satisfied with stability.

My drawings are not propaganda or agitation. They’re food for thought, attempting to say that we can no longer afford the luxury of acquiescing to membership in the common consumer class, indifferent to what is happening around us.

ALMATY

When I’m away from Kazakhstan, I miss the handful of people who stayed here. But when I am here, I feel cramped. And now I miss Istanbul.

I arrived in Almaty in March. When I went out on my first walk with my child, I wanted to cry. I did not want him to breathe this air. I checked the pollution rates on AirKaz and the Air Quality app. Their recommendation was to not even open windows to air out the house. I thought that I wouldn’t go outside at all, and that would be my choice. I even thought that it might be nice to go to Tekeli for a while, just to get some fresh air.

But, over time, a person gets used to everything. Now, a month later, I go out and no longer notice the smell of smog.

DEVELOPMENT

One of the reasons why I worked at a popular-science journal was the opportunity to develop new neural connections. To illustrate a complex article, you first need to understand it. Our brains are lazy; everything needs to be consciously learned. We need to raise the bar of our minds, pulling ourselves up and asking: What the hell am I doing? What is my goal? Will I be happier if I buy something? It strikes me that we should rid ourselves of all unnecessary things, including toxic thoughts and people.

I was once drawing a picture about how one could extrapolate the workings of any patriarchal family onto the government. I had this thought that I, like everyone, probably, have some person among my relatives who works in the organs of the state. This creates a sense of stability, as if everything is in my grasp, as if I hacked the system. And expressions like: "settle the affair" or "solve” come to our lips as if they were transmitted to us by blood. Once in Istanbul, faced with bureaucracy, caught myself having this treacherous thought: "Is there really no way to settle this question?" I immediately felt ashamed. As long as there is this idea that every problem can be easily “solved,” we won’t be inclined to fight corruption.

Our women are only slowly beginning to liberate themselves and fight for their rights: to work equally alongside men and to share responsibilities at home. But even so, I notice a distorted understanding of feminism, even among women in my circles. They say: "I am not a feminist, but..." They fear stigma. We have a very aggressive society, and it is difficult to exist in it.

Now I want to take my art precisely in this direction: to draw about women, about stigma, about inner freedom. I want to say: “Girls, the whole world is in front of you — travel, work, find yourself, become neurobiologists, oceanologists, artists! The clock doesn’t stop ticking. I’ve checked."